I was introduced to wargames (Avalon Hill, of course) about 55 years ago when I was seven years old by my buddy Carl Hoffman who lived down the street. Carl and I ended up owning every Avalon Hill wargame and we played them all. Eventually, Carl and his family moved away (I think Carl became a professor at LSU but I can’t confirm that) and I was faced with the grim realization that all of us Grognards inevitably confront: there was nobody to play wargames with.

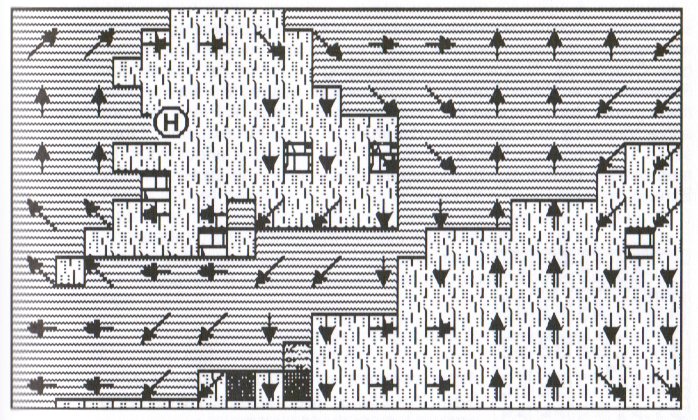

Over the years I would occasionally find someone interested in playing (or, more likely, coerce a friend who really had little interest in wargames) to set up a game but rarely would we ever complete a full campaign or battle. By the late 1970s playing wargames for me was a rare event (the one exception being my good friend from my undergrad college days, Corkey Custer). Then, about this time, I saw an episode of PBS’s NOVA on what was then the infancy of Computer Graphics (CGI). There, flickering on my black & white TV, was what we would eventually call ‘wire frame’ 3D. Wire frame 3D just shows the edges of 3D objects. They are not filled in with a texture (as CGI is done now). Computers just didn’t have the processing power to pull this off back in the late ’70s and ’80s. But, I immediately thought to myself, “this technique could be used to render 3D battlefields!” And that was the spark from UMS: The Universal Military Simulator was born.

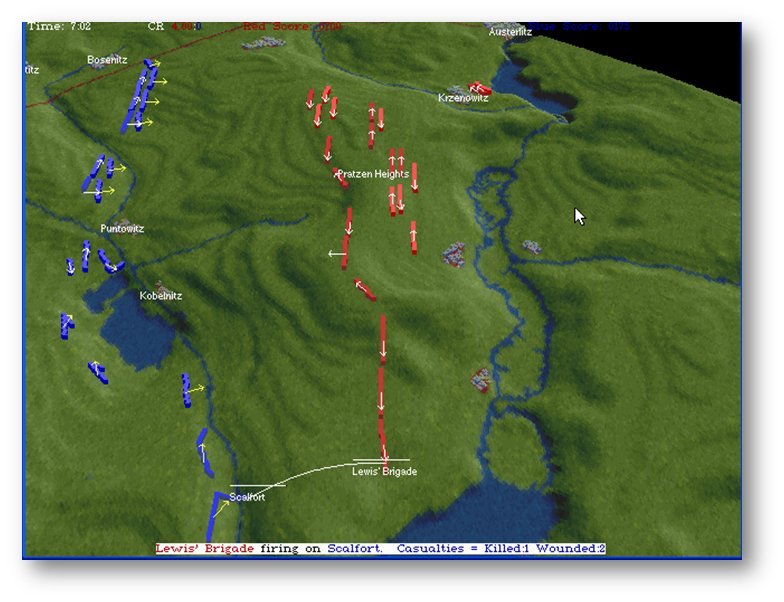

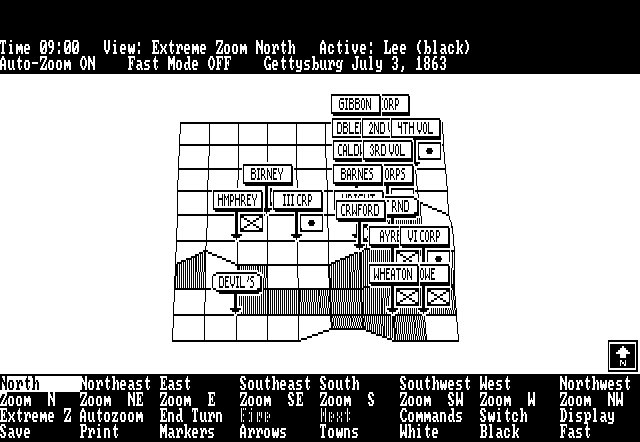

Screen capture of the original UMS running in 640 x 400 x 2 resolution in MS DOS. This is an example of wire frame 3D.

By the mid 1980s I was about to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in computer animation and, more importantly, a working demo of UMS. I had hypothesized that one of the biggest selling points of computer wargames was the ability to always have an opponent handy (the artificial intelligence or AI). I borrowed a copy of the Software Writers Market from the library and sent out dozens (maybe even hundreds) of letters and, eventually, papered an entire wall of my apartment with rejection letters from game publishers. But, Dr. Ed Bever, who designed Microprose’s Crusade in Europe, Decision in the Desert and NATO Commander (pretty much the only computer wargames that were out at the time) saw my pitch letter and gave me a call. Microprose wasn’t interested in publishing UMS per se, rather their CEO, “Wild Bill” Stealey, wanted me to come work for Microprose (and they would own UMS). That deal didn’t appeal to me but a short time later, at the 1986 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, Ed Bever introduced me to Microprose’s competitors, Firebird/Rainbird. Within 48 hours I had my first game publishing deal.

Crusade in Europe from Microprose (1985) designed by Dr. Ed Bever, originally programming by Sid Meir.

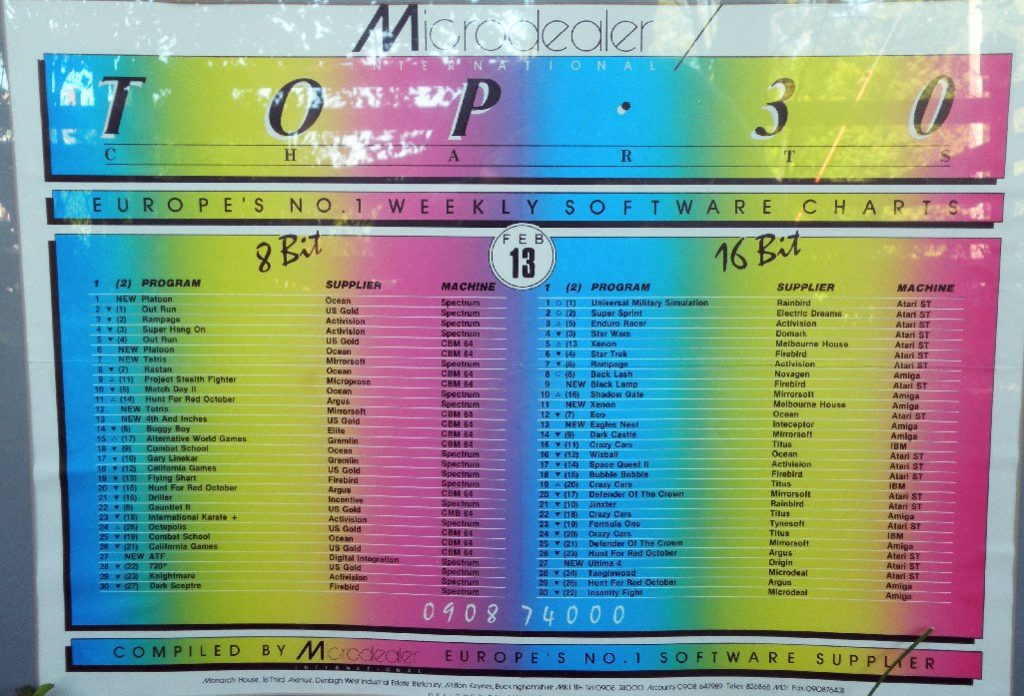

UMS sold about 128,000 units and was the #1 game in the US and Europe for a while.

The European Microdealer Top 30 Chart with UMS as #1 with a bullet on the 16-bit game chart. What other classic games can you find on the charts? (Click to enlarge)

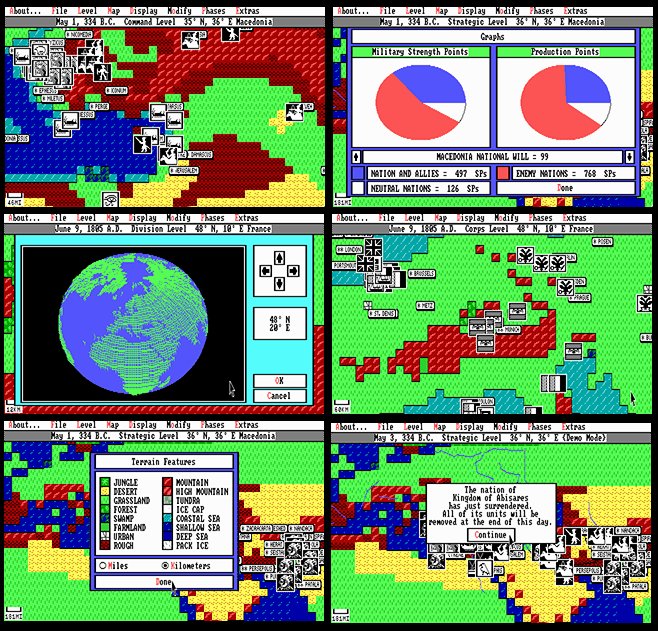

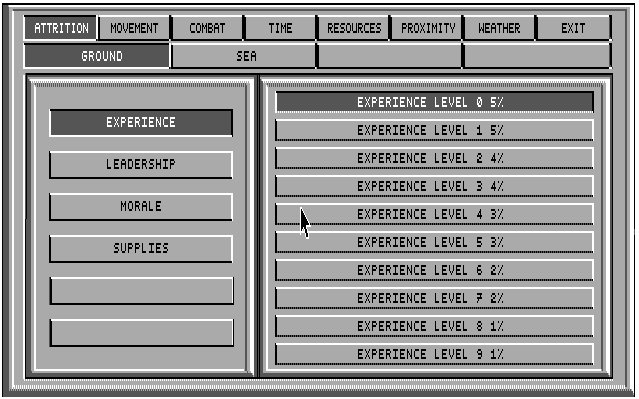

Ed Bever helped on the design of UMS II: Nations at War which was an extremely ambitious global wargame that had unprecedented detail and allowed the user to edit numerous variables and equations:

An example of the numerous variables that the user could adjust in UMS II.; in this case adjusting the attrition level based on experience for ground units. Macintosh screen shot. Click to enlarge.

UMS II was named “Wargame of the Year” by Strategy Plus magazine and enjoyed strong sales. In many ways it was the ‘ultimate’ in complex wargaming. It was far more detailed than any other wargame I’ve seen before or since (and that includes my work on DARPA, Department of Defense, US Army, Office of Naval Research and Modeling Simulation Information Analysis Center (MSIAC) wargames. Ironically, it was published by Microprose because they bought out Firebird/Rainbird and with it my publishing contract.

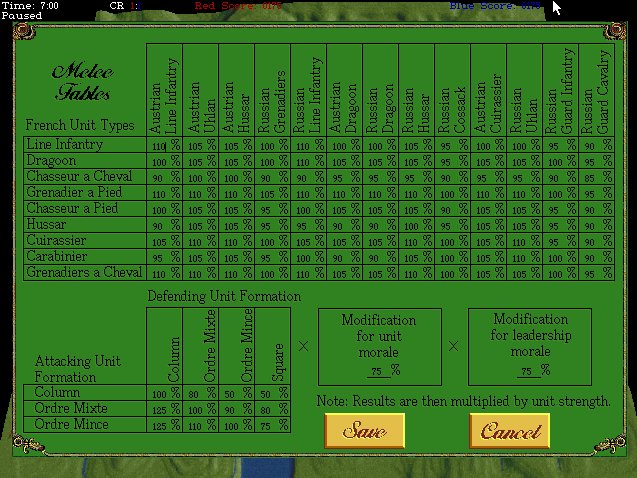

My next wargame, in 1993, was The War College. We used data from US Geological Survey to create the 3D maps. Again, it was very detailed and allowed the user to edit combat values and featured an interactive hyperlinked history of each scenario (it shipped with Antietam, Austerlitz, Pharsalus and Tannenberg). Unfortunately, our publisher, GameTek, pretty much ceased to exist just as we were about to release this game. To this day I have no idea how many units it sold. We never got a royalty statement.

The War College also had an interactive history for each battle (screen shot from MS DOS, click to enlarge).

The War College allowed users to adjust melee effectiveness and values. MS DOS screen shot, click to enlarge.

I also would be terribly remiss if I did not mention my good friends who worked on various ports of the above mentioned games, Ed Isenberg (Amiga and MS DOS), Andy Kanakares (Apple IIGS and MS DOS) and Mike Pash (MS DOS).

One of the problems of getting old is that your stories get longer to tell. This blog post is far longer than I intended and we haven’t even got to this century and all my research into computational military reasoning (Tactical and Strategic AI) and my new wargame, General Staff. I’m afraid we’ll have to end this here and pick up the story in Part 2 next week.