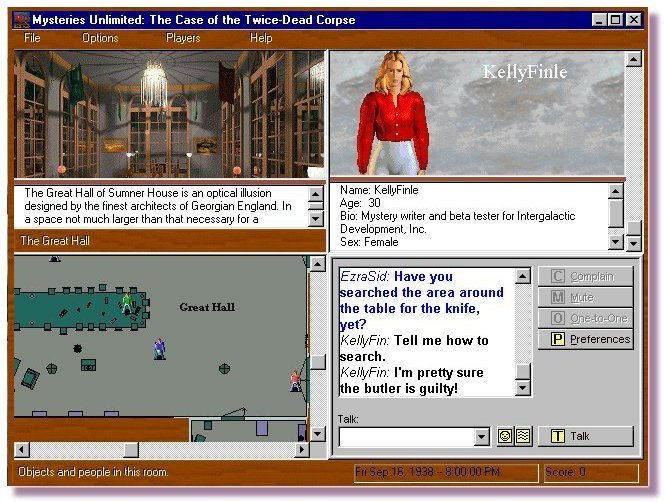

After The War College I created a couple of non-wargames including Online Mysteries, a massive multiplayer online mystery game that was written for AOL’s WorldPlay. WorldPlay was envisioned to be a 3D online world populated with avatars. It was similar in concept to Second Life but, like a lot of great ideas, was ahead of its time. AOL shut WorldPlay down before most of the games, including Online Mysteries, launched.

Mysteries Unlimited screen shot (Windows) was a massively multiplayer online mystery game created for AOL/WorldPlay (click to enlarge).

By 2000 the game publishing industry was going through another convulsion of consolidations, buyouts and contractions. Publishers were producing fewer games but the ones that were being created had large teams, long development cycles and massive budgets. The days when an independent developer could pitch a game idea, get an advance and then develop it outside of a publisher’s studio were gone. And the last thing that the big publishers were interested in were wargames.

Over the previous fifteen years I had received inquiries from active duty military and Pentagon project managers about my wargames (known as Commercial Off The Shelf, or COTS, in Pentagon-lingo) and if I would be available to consult on various wargaming projects. Unfortunately, I was lacking a key prerequisite for this: a doctorate. I returned to academia, first to a small local college where I also taught computer game design and in 2003 I was accepted in the computer science PhD program at the University of Iowa (one of the oldest computer science departments in the world).

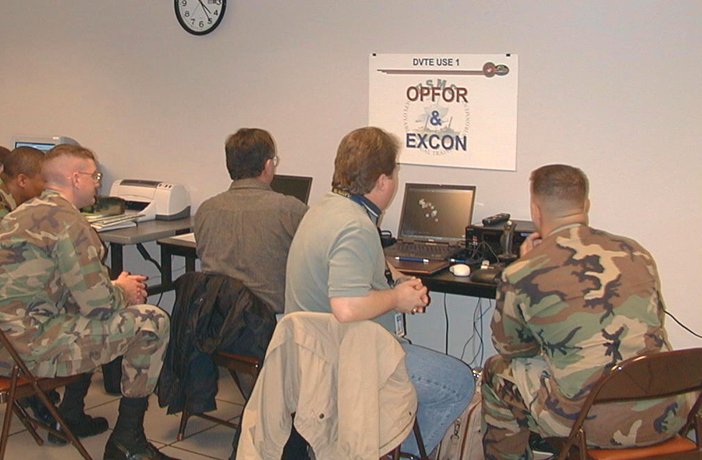

Before I ever set foot in MacLean Hall (the home of the Department of Computer Science at the University of Iowa) I knew what I would spend the next six years of my life researching and studying: tactical and strategic AI (I would eventually coin the phrase ‘computational military reasoning’ to describe this field). What I soon discovered was that very little work had ever been done in this research area. What was even more surprising was my discovery that most ‘professional’ military wargames (i.e. wargames used by the US Army, NATO, England, Australia, France, etc.) had absolutely no AI whatsoever. Instead, they employed ‘pucksters’ (usually retired military officers) who made all the moves for OPFOR (Opposition Forces, AKA ‘the enemy’) from another computer in another room.

Pucksters are humans (usually retired military officers) who make the decisions and moves for enemy (Opposition Forces = OPFOR) units during a wargame. Note the sign OPFOR & EXCON (Exercise Control) over the puckster’s work station.

To earn a doctorate at an American ‘Research One’ university requires 90 graduate credits (about 30 classes), a GPA > 3.5 (out of 4.0) and passing three major examinations. The first examination on the road to a doctorate is the Qualifying Examination (or Q Exam as everyone calls it). The topic of my Q exam was “An Analysis of Dimdal’s (ex-Jonsson’s) ‘An Optimal Pathfinder for Vehicles in Real-World Terrain Maps’.” This is the area of computer science and graph theory known as ‘least weighted path algorithms’. GPS devices and Map apps use a least weighted path algorithm, except they’re only interested in roads; they don’t consider terrain, slope and other things (that are important to a military unit maneuvering on a battlefield).

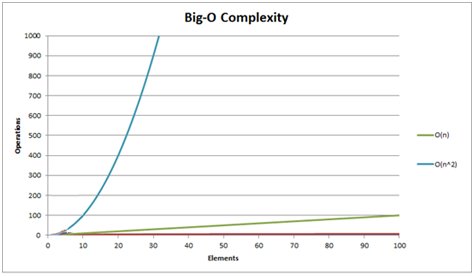

Now, if you were to wander into the ivied halls of academic computer science (like MacLean Hall) and inquire of a tenured faculty member how to calculate the fastest path between two points on a sparse grid they would almost certainly reply to you, “Dijkstra’s algorithm.” Dr. Dijkstra invented his algorithm in 1956 and it works like this: first calculate the distance between every point on the map and every other point on the map. Then figure out the fastest path. Yeah, it’s that obvious, and painfully slow. In fact, it’s so slow that it isn’t used for GPS or game AI. In computer science we us ‘Big O’ notation to describe how fast (or slow) an algorithm takes to run. Dijkstra’s algorithm runs in O(|V|2). This means that as the number of vertices, or points on the map, (that’s the |V| part) increases, the time it takes for the entire algorithm to complete goes up by the square of the number of vertices. In other words, as the map gets bigger the algorithm gets a lot slower.

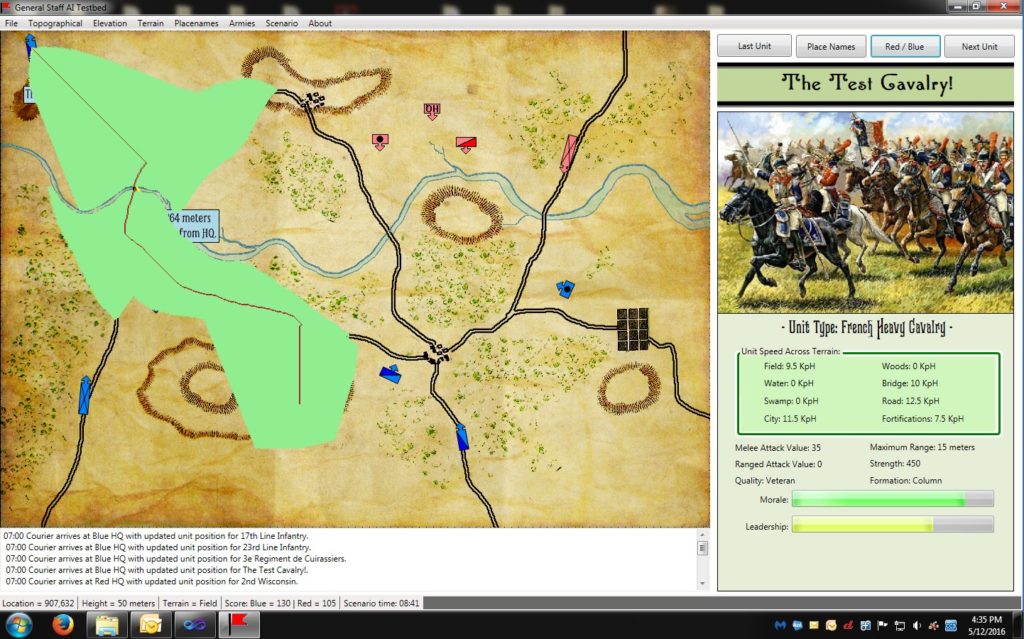

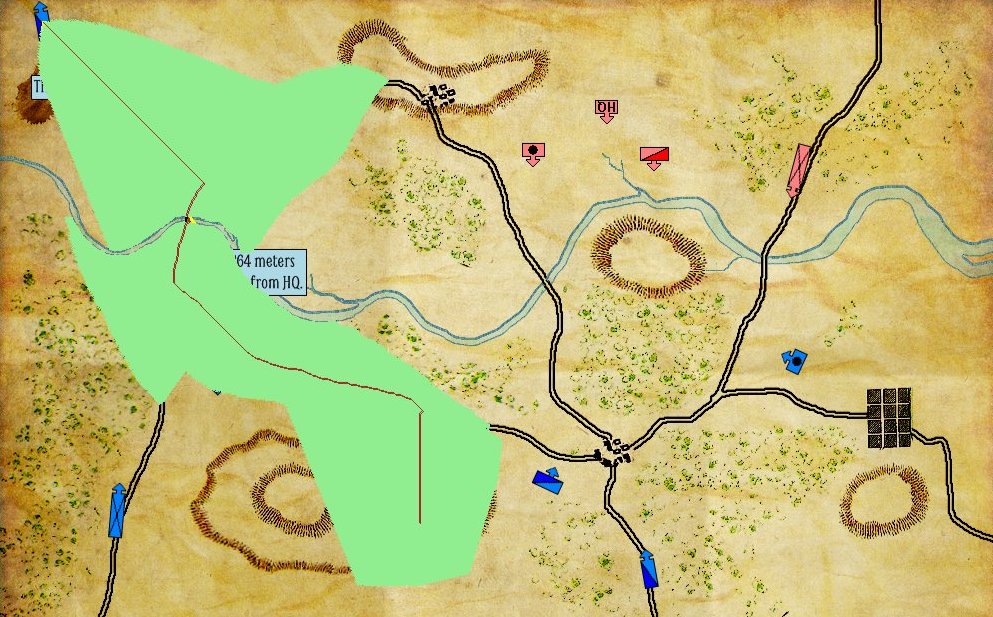

Dimdal, and I and most of the gaming world do not use Dijkstra’s algorithm, Instead we use A* (pronounced ‘A Star’) which was designed in 1968 primarily by Nils Nilsson with later improvements by Peter Hart and Bertram Raphael. Below is an example of A* used in General Staff (note that the algorithm doesn’t look at every point on the map, just ones that it thinks are relevant to the problem at hand). A* runs in O(n) time.

A screen shot of A* algorithm running. The green areas are where the algorithm searched for a least weighted path, the brown line is the shortest path (mostly following a road).

Graph showing the difference between Dijkstra’s algorithm and the A* algorithm. The blue line that increases rapidly shows that Dijkstra’s algorithm takes much more time as the map gets bigger. A* (the green line) is not affected as much by the size of the map.

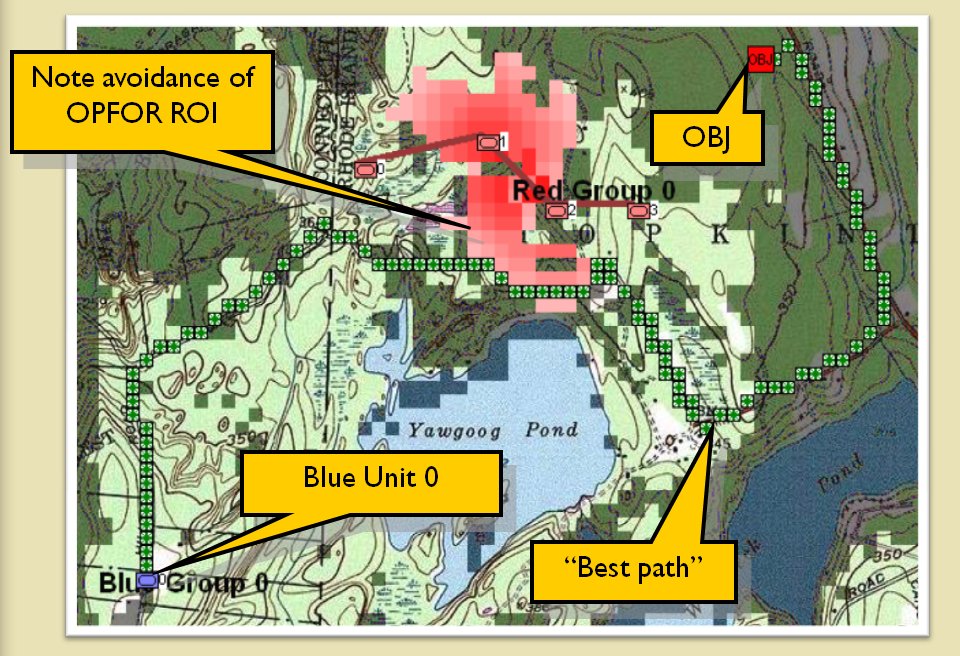

As part of my research into computational military reasoning I made further modifications to A* to take into effect the slope of the terrain (which can affect speed of some units), the range of enemy units (OPFOR ROI, e.g. areas controlled by enemy artillery) and to avoid enemy line of sight (LOS). My MATE (Machine Analysis of Tactical Environments) project used all of these options:

A slide from my presentation to DARPA showing how my modified A* avoids enemy range of weapons. The likelihood of taking casualties is indicated by the darkness of the red coloring.

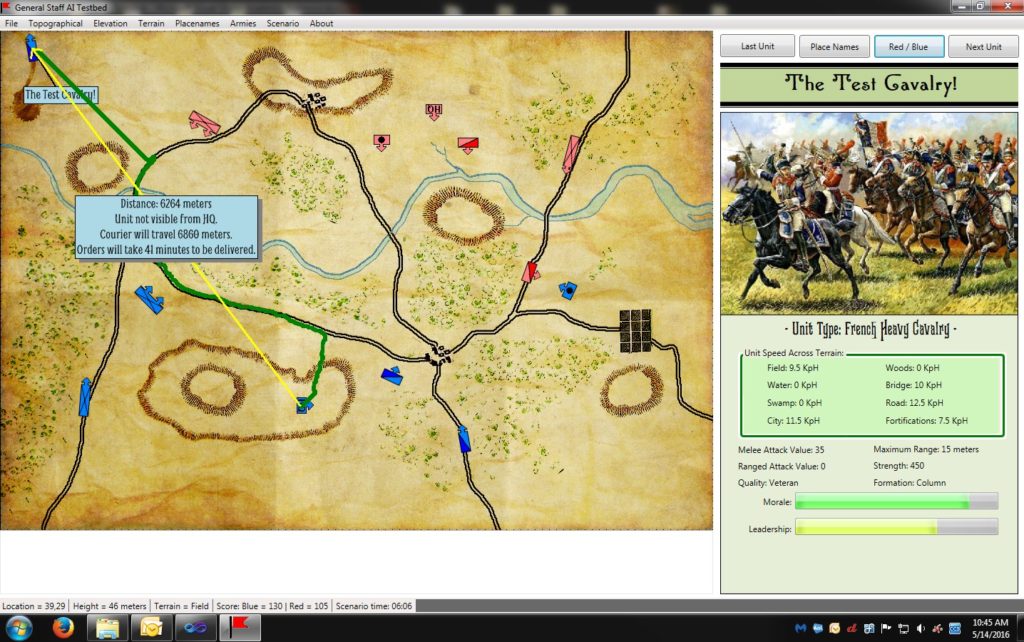

While working on General Staff I came up with a new optimization of the A* algorithm which I’ve called EZRoadStar. EZRoadStar first looks at the roadnet and attempts to utilize it for rapid troop movement. Only after ascertaining how far using roads will get it to its goal does the algorithm look for nonroad paths. EZRoadStar is much faster than traditional A*; especially for wargames and military simulations.

An example of the EZRoadStar least weighted path algorithm. What’s the fastest way from point A to point B (the yellow arrow)? Taking the road, of course. This algorithm looks at a battlefield like a commander and utilizes the roadnet first before looking at other options. Click to enlarge.

Well, this wargame may be 55 years in the making and it looks like describing some of the key things that went into it may take almost as long. Clearly, I’m going to have to continue this story with yet another post. We’ve just barely scratched the surface of my work on wargame AI. The next installment will (hopefully) cover algorithms for ‘the five canonical offensive maneuvers’ (i.e. The Envelopment Maneuver, The Turning Maneuver, Penetration, Infiltration and Frontal Assault. These are the algorithms that are ‘under the hood’ of General Staff. If any of my readers would like to know more about these topics (links to my published papers on the subject or whatever) please drop me a line at Ezra [at] RiverviewAI.com.