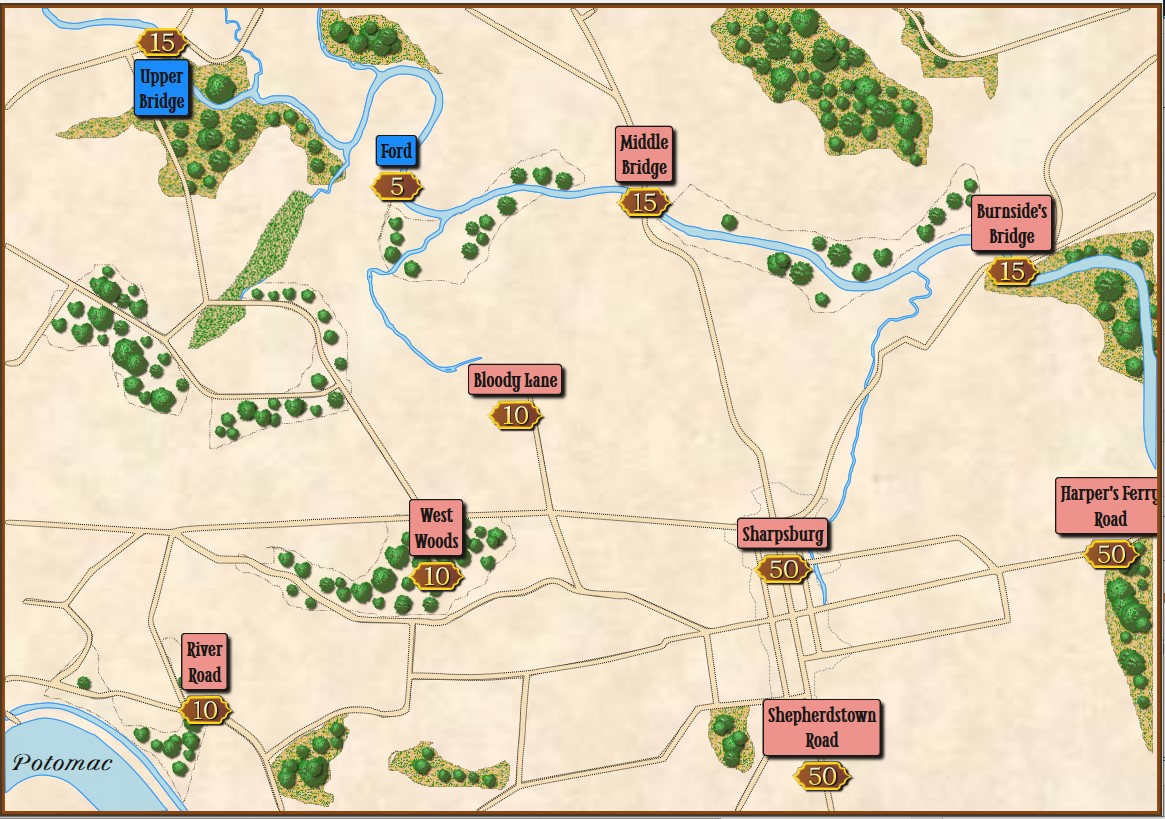

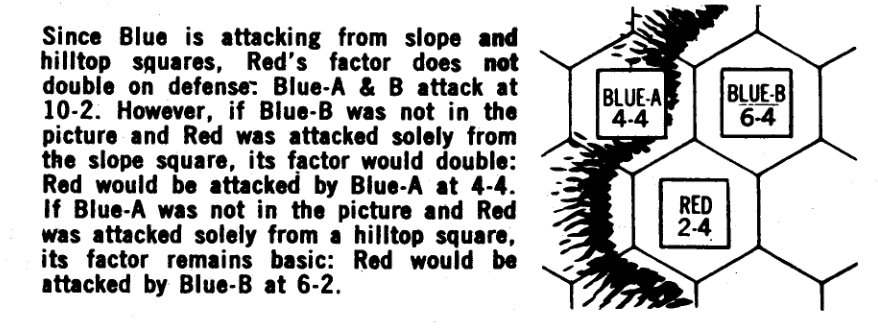

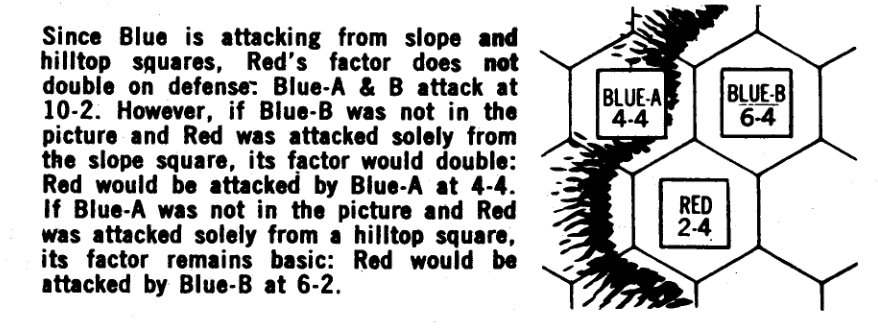

Rules for how slopes effect attack and defense from Avalon Hill’s Gettysburg (1960 edition). Author’s collection. Click to enlarge.

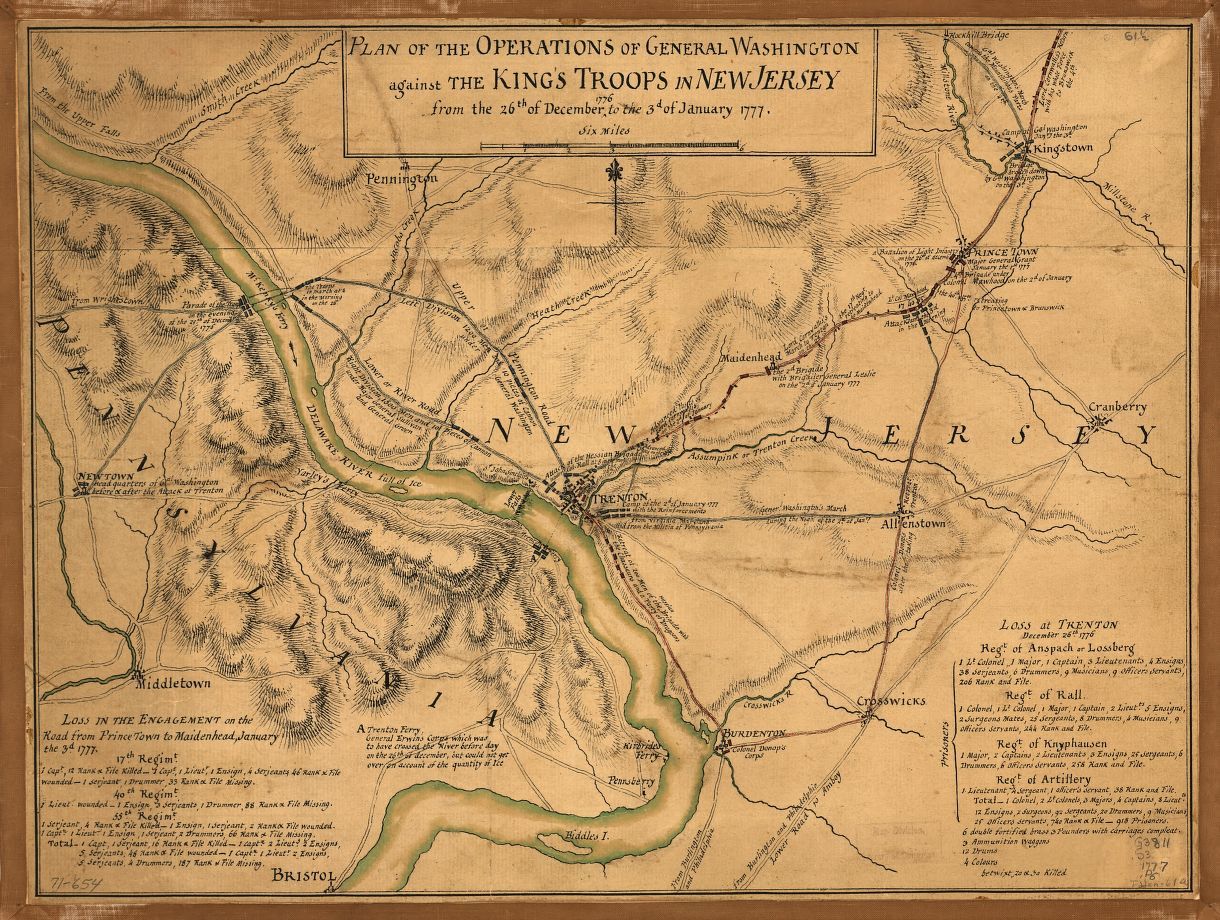

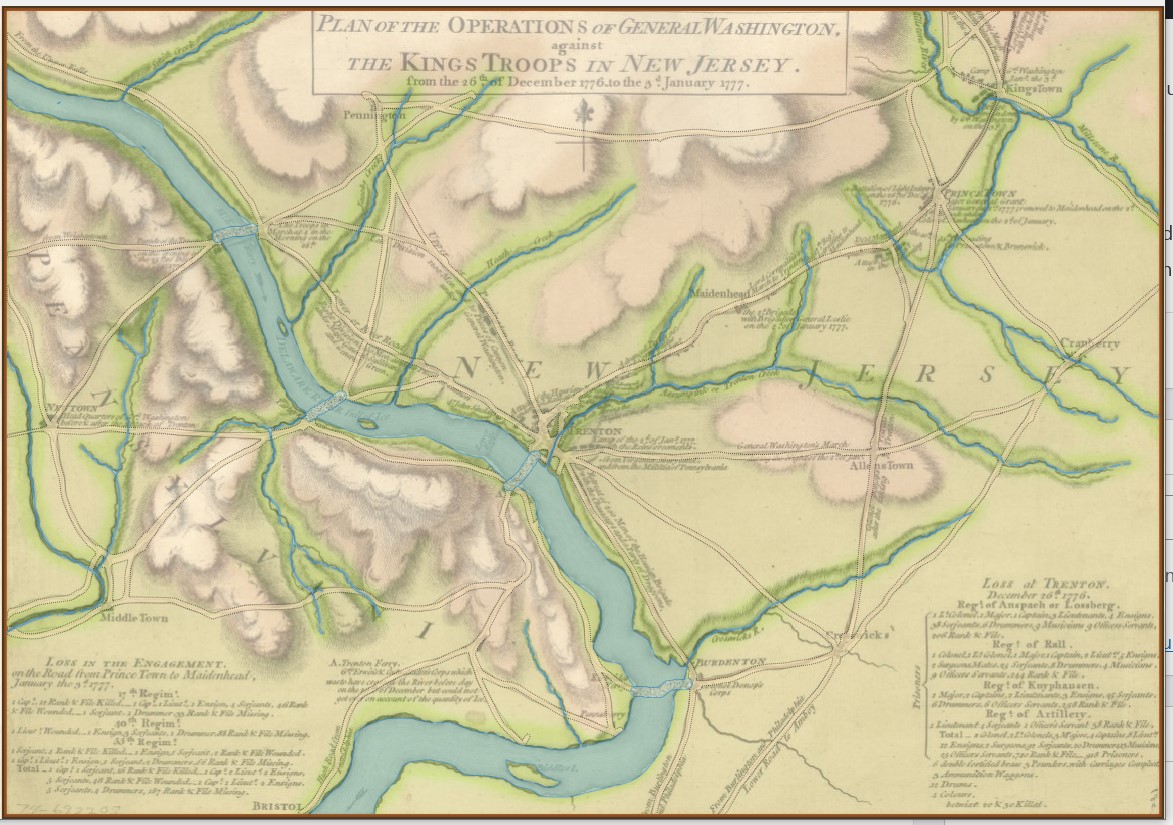

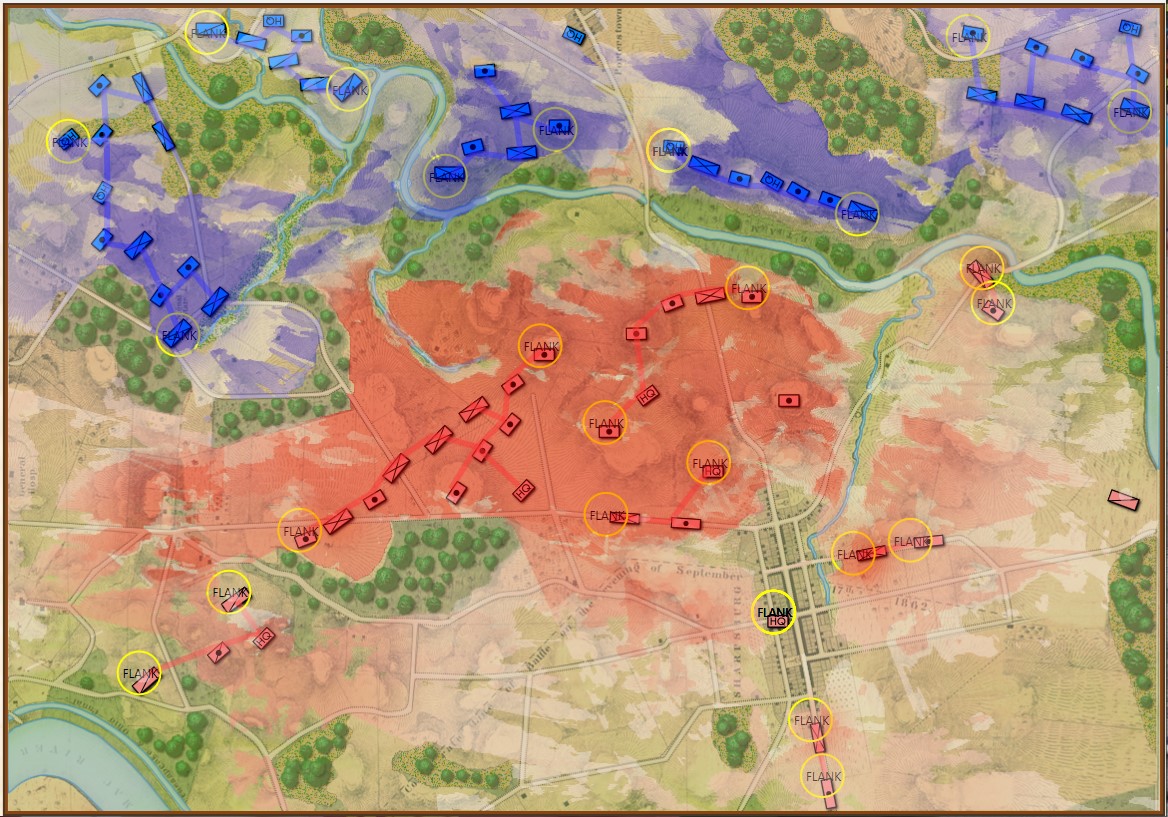

One of the first rules that we all learned when we began to play wargames (at least this was true of early Avalon Hill games for me way back in the 1960s) was that if the defending unit was on a hill and the attacking unit was on the slope, the defender’s ‘defense factor’ was doubled. Under some circumstances, a defending unit could even have its defense factor tripled (see right). And, yes, there were situations (see below) where an enfilading attacking unit could negate the defenders 2:1 advantage. For my entire wargaming life – over fifty years now – this basic rule of thumb applied: a unit on a hill was twice as strong, defensively, than it would be on the plains below. I’ve used this ‘defensive factor multiplier’ in every wargame I’ve designed going back to UMS in the 1980s. I never gave it a second’s thought. Until now.

Detail of rules from Avalon Hill’s Waterloo (1962) showing when a defender’s strength is doubled on a hill and when the effect is negated.

General Staff has no concept of “defense factor.” Think about it, what is a ‘defensive factor’? It seems to act like armor of some sort. It certainly is a valid concept in naval warfare or armored warfare or jousting, but it doesn’t apply in 18th and 19th century warfare that General Staff: Black Powder is designed to simulate. Instead, units in General Staff are weapons platforms. Units project firepower which result in casualties. Indeed, all combat resolution boils down to this equation: How many casualties did this unit inflict on that unit?

Since there is no ‘defensive factor’ to multiply by two for being on a hill defending against an attacker climbing a slope, how or what does General Staff multiply or divide? What is the source for the 2:1 defense factor multiplier for having the high ground? These were the questions that I recently investigated.

It turns out there has been very little research done on the subject of military movement on slopes of various degrees, and the effect of angle of slope on defending a position against a unit attacking up slope. Yes, the U. S. Army has published this on foot marches and slopes but it doesn’t cover 19th century cavalry, artillery, horse artillery, etc.).

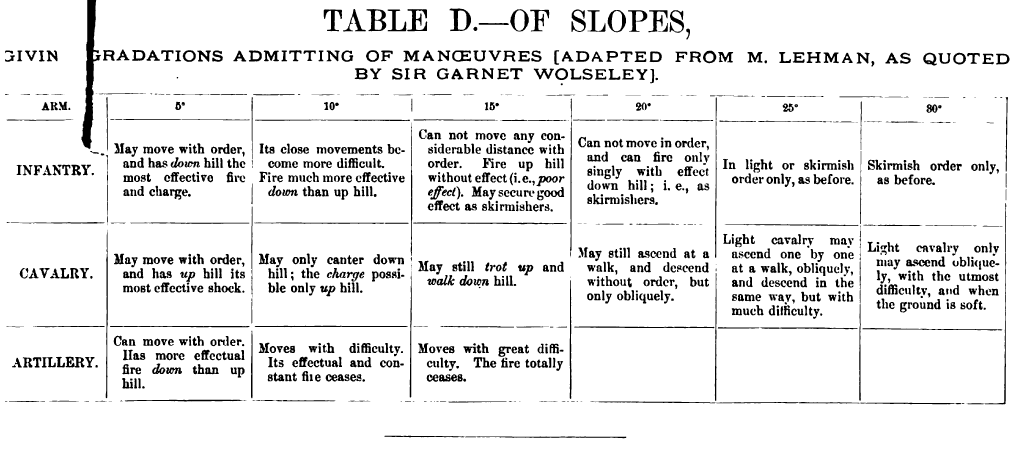

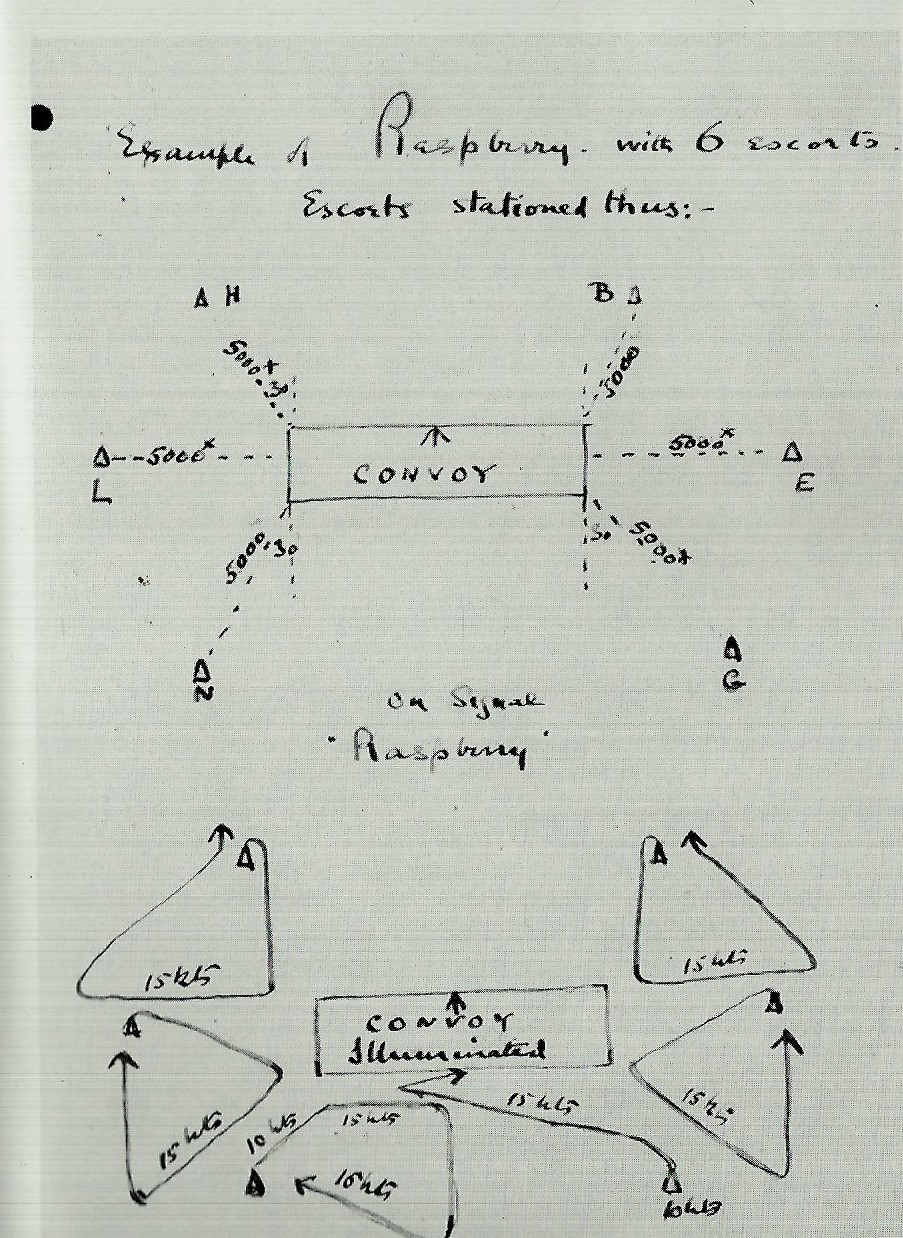

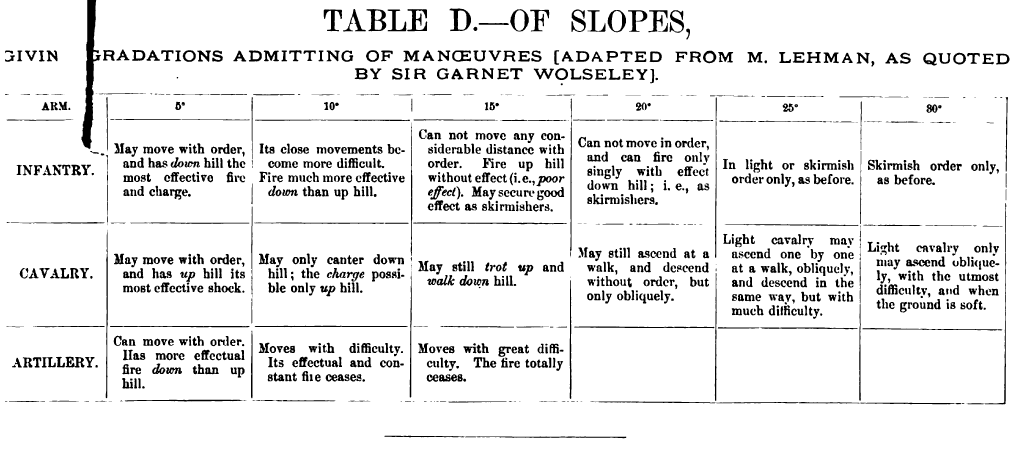

What I was looking for was a table that cross-indexed angle of slope with its effect on attack, defense and movement. What I found was Table D, (below) from the rules for Charles Totten’s Strategos: The Advanced Game. on the Grogheads.com site:

From. “Charles Totten’s Strategos: The Advanced Game.” found at Grogheads.com. Published in 1890.

What this chart shows is:

- Unit types respond differently to moving up or down different slopes; e.g. no artillery can ascend a slope greater than 15°, no cavalry can descend a slope greater than 30°, and infantry can only ascend slopes of greater than 30° in skirmish formation.

- Having superior elevation does not impart any defensive advantage by itself.

- Having superior elevation on a steep slope can actually be a defensive disadvantage; e.g. artillery cannot fire down a 15° slope, and cavalry cannot charge down slopes greater than 15°.

- Units firing uphill have increasingly less effect as the angle of slope increases; e.g. infantry has limited or no effect firing uphill at greater than a 20° slope, cavalry cannot charge up a slope greater than 15°, and artillery has no effect when firing up a slope greater 15°. Indeed, this is where the the traditional defensive advantage of holding the high ground derives from: defensive fire is not more effective, rather offensive fire is much less effective when attacking uphill.

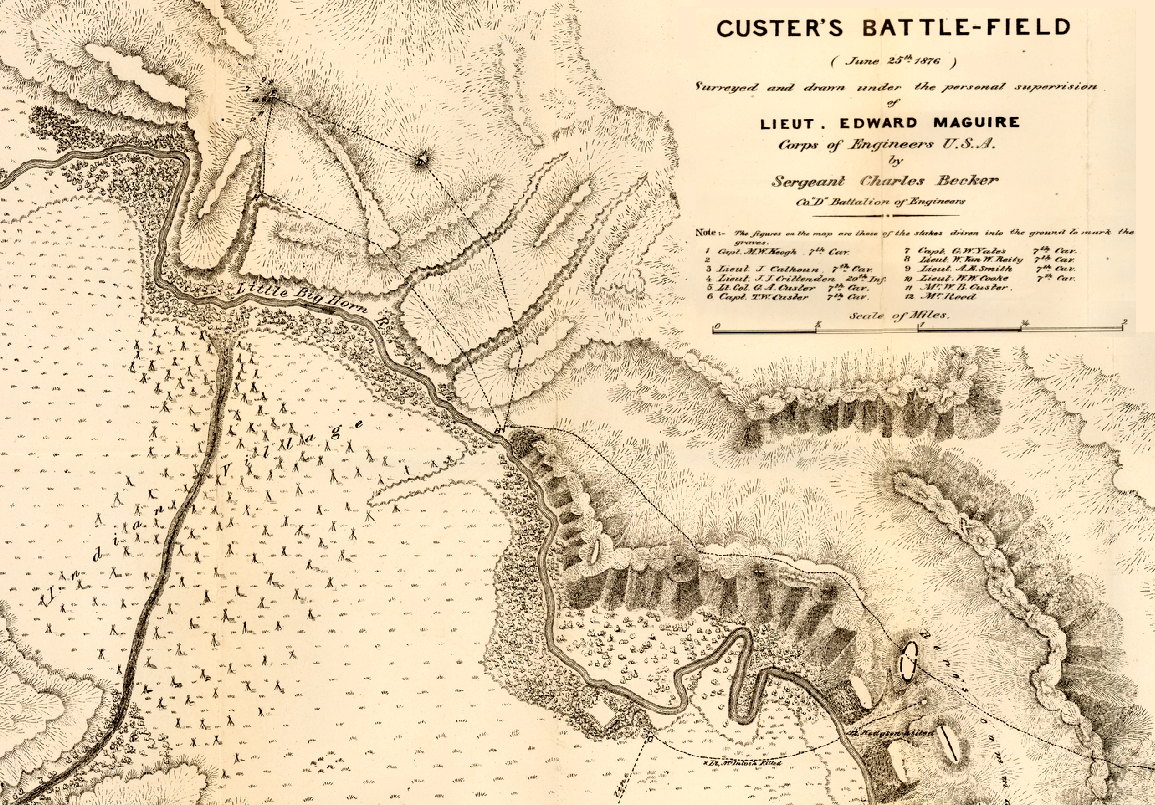

If we look at two battles of the American Civil War that are known for assaults up steep slopes (Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862 and Missionary Ridge, November 23, 1863) we find that the values in Table D, above, are largely validated.

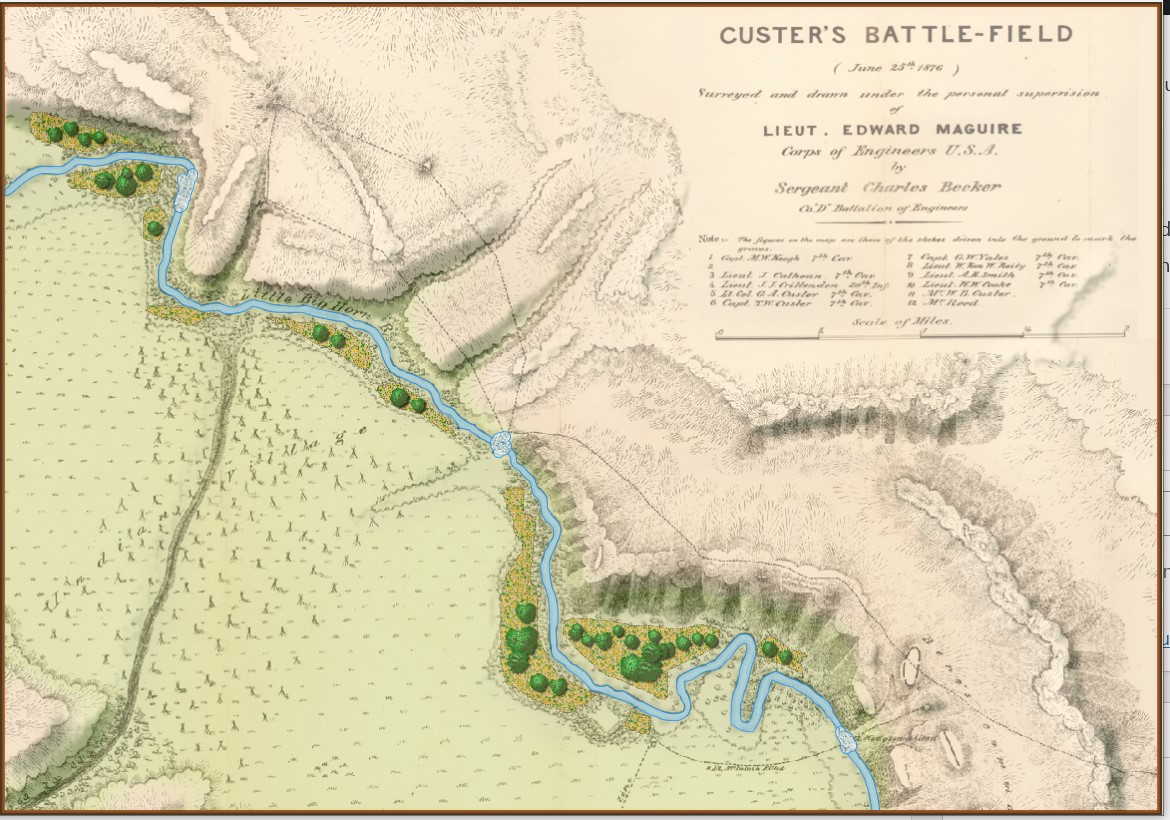

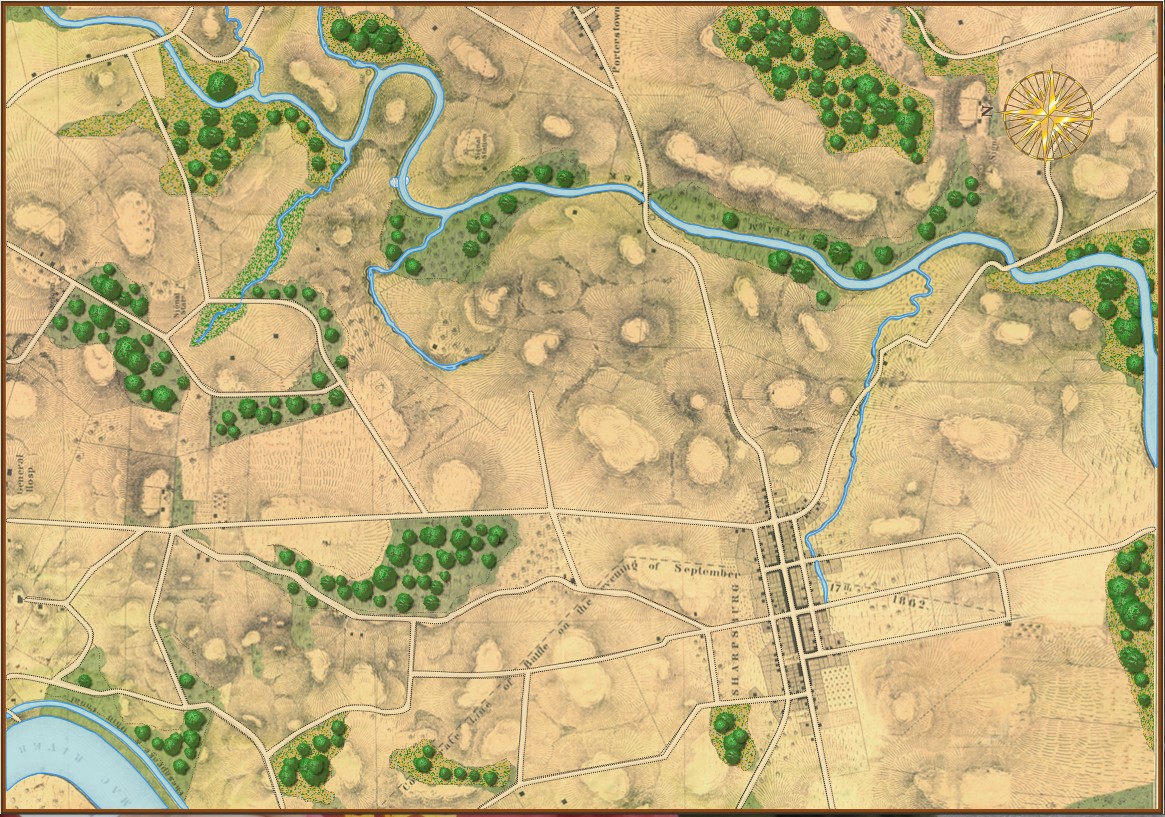

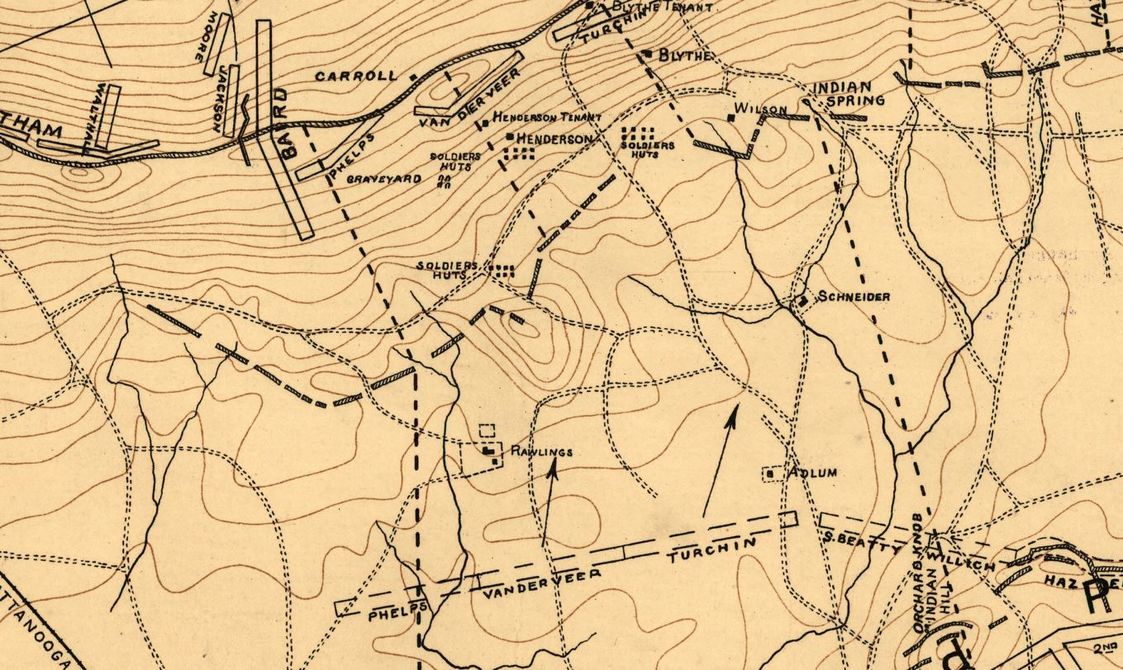

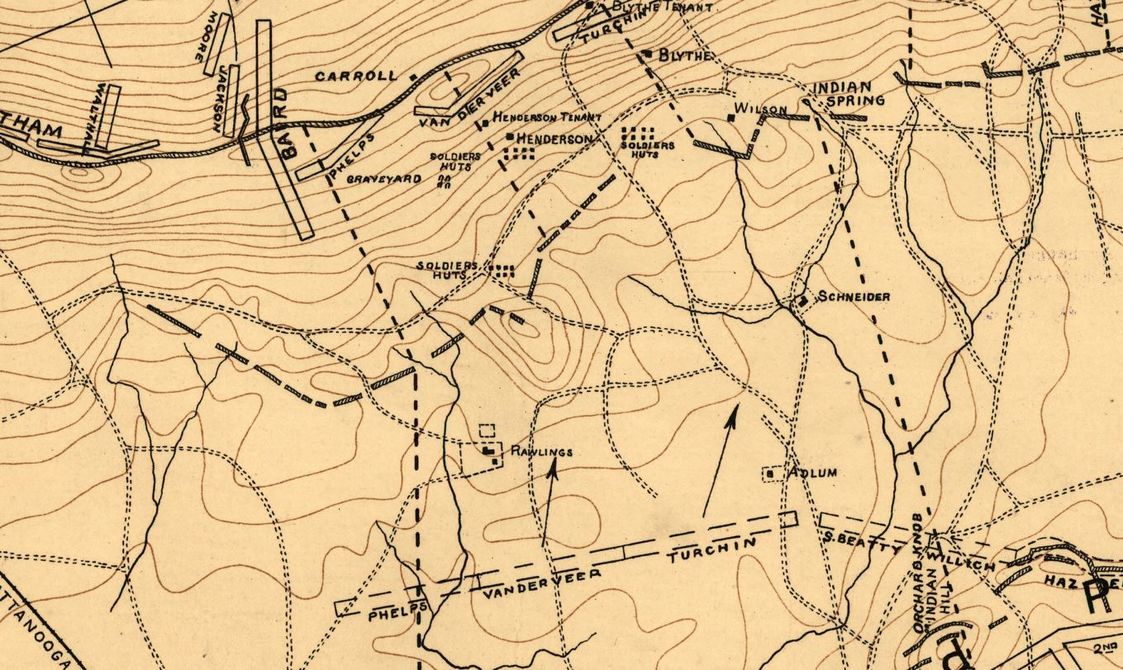

Detail of map of Missionary Ridge from the Library of Congress. The crest of the ridge is about 275 feet above the plain below. In numerous places, the slope is greater than 20°.

The story of the successful Union attack on Missionary Ridge is legendary: Union forces originally assigned to capture the rifle pits at the base of the ridge pushed up the slope without orders, primarily to escape defensive fire from above. They scaled the ridge in a loose, skirmish formation, not firing until they reached the crest.

As we can see from the above map the slope of the Union attack up Missionary Ridge is, at points, greater than 20°. In Brent Nosworthy’s, Roll Call to Destiny: The Soldier’s Eye View of Civil War Battles he writes (page 250), “One of the most notable characteristics of this engagement was the relatively light number of casualties suffered by Van Derveer’s attack force, even though it had to break through two sets of fieldworks.” “To the untrained eye looking at the defenses way up on Missionary Ridge… the Confederate position must have appeared impressive, possibly impregnable, and if not impregnable, then capturable only after the expenditure of many lives. This was the opinion of the Confederate commanders who had chosen to defend the position. (page 252)” “Unfortunately for the Confederates, the military reality was quite the opposite. A high ridge immediately above a steep gradient is one of the worst imaginable defensive positions, about equivalent to placing one’s forces in a line with their back to a river and no avenue of retreat. (page 253). ”

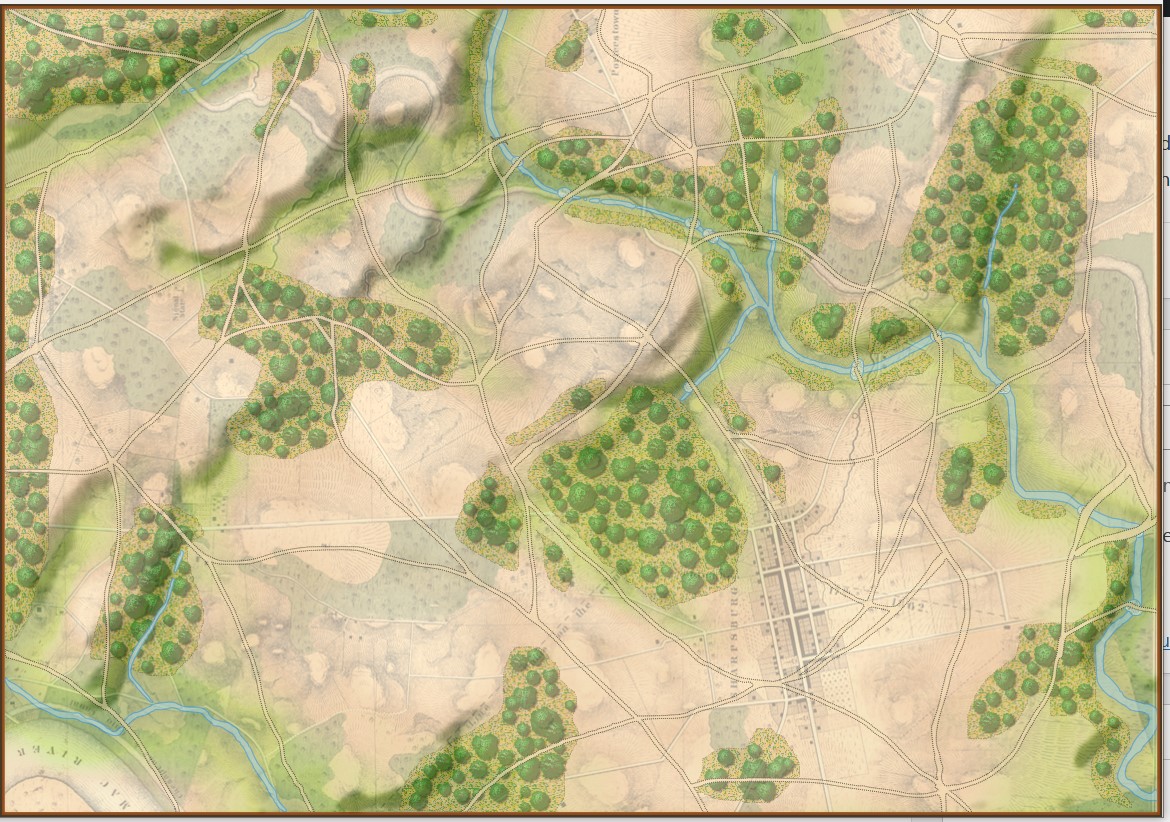

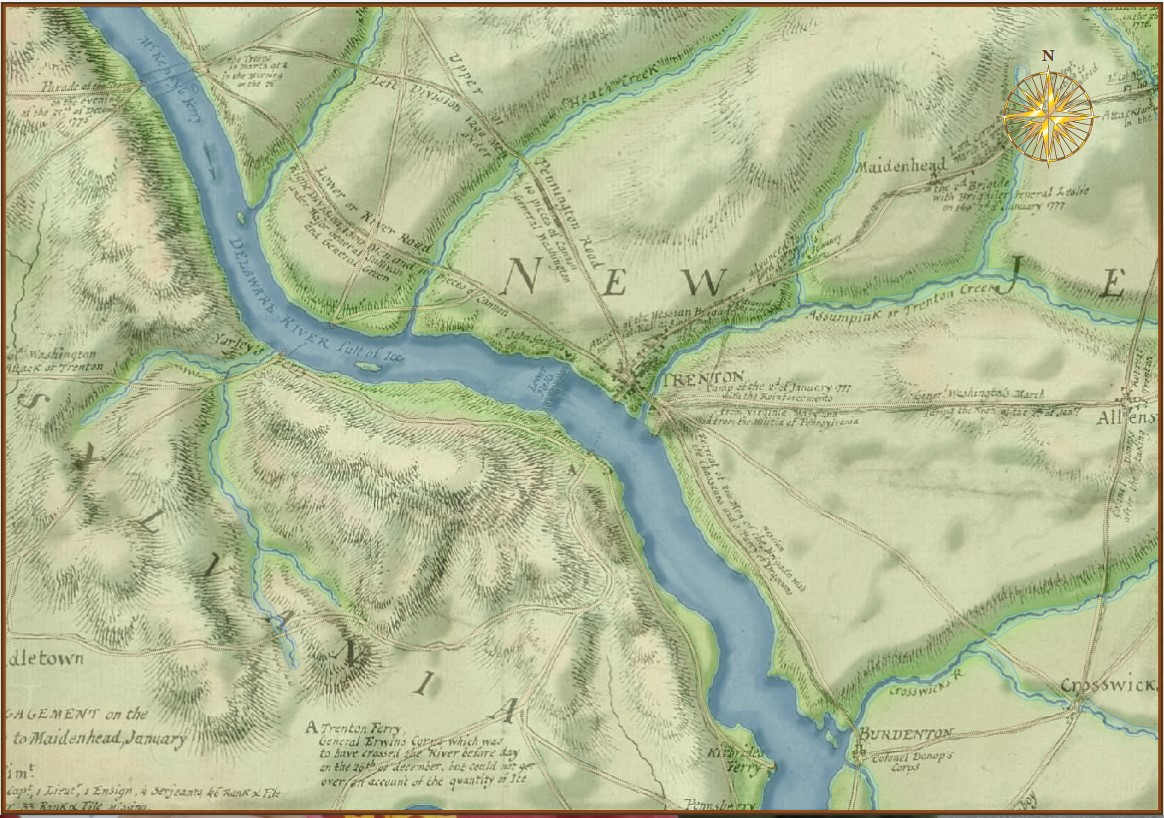

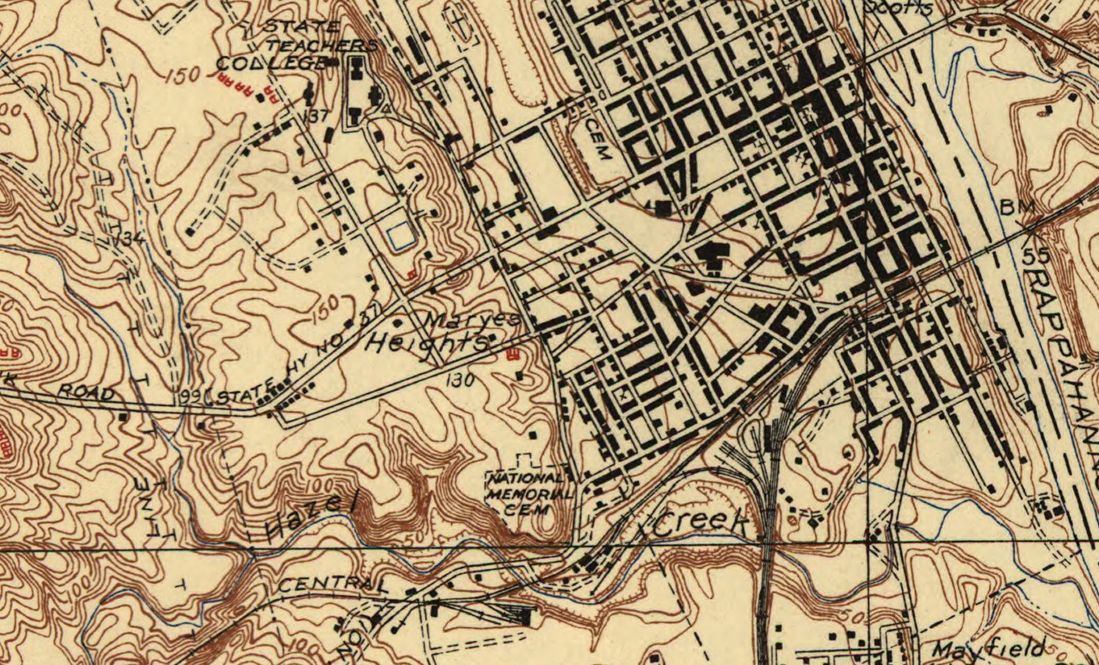

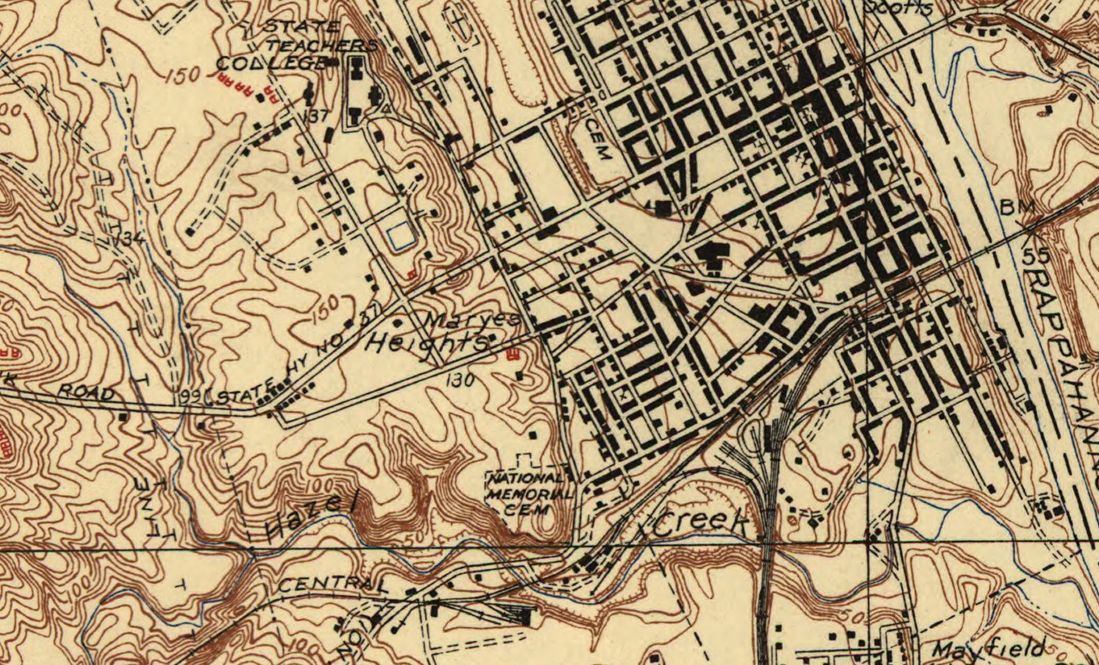

This map of Fredericksburg from the Library of Congress (1931) shows a 90 foot rise in elevation above the plain for Marye’s Heights.

Union forces attacking up the gentler slope at Fredericksburg were not so fortunate. Except in a few steep places that offered shelter from Confederate artillery most of the Union attack was under constant fire. Quoting from Nosworthy’s Roll Call to Destiny (page 129), “a British artist on assignment for the Illustrated London News would recall the effect of the artillery fire on the advancing Union lines: ‘I could see the grape, shell, and canister from the guns of the Washington Artillery mow great avenues in the masses of Federal troops rushing to the assault.'”

Nosworthy, in, The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War, writes (422-3), “It had long been a general maxim that artillery should only be placed at the top of a slope which it could defend by itself. The artillery had to be able to direct an unobstructed fire against the base of the hill otherwise the enemy force could form in the dead zone and begin its assault up the hill unopposed by the artillery. Officers were cautioned, however, against ever placing artillery on either steep hills or high elevations. Ideally, artillery was placed on elevations whose height was 1% of the distance to the target and were never to be placed upon hills where the elevation was greater than 7% of this distance. When artillery was required to defend a lofty hill or elevation, whose height made it impossible for the artillery to command the base, artillery officers were advised, if at all possible, to place the battery lower along the slope, such as at the halfway point.” The problem of course, was that artillery could not lower the barrels of their guns sufficiently to fire down steep slopes.

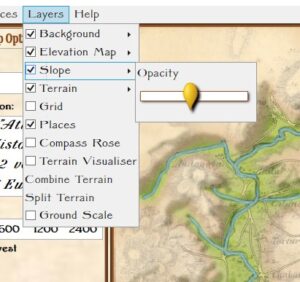

Slopes in General Staff

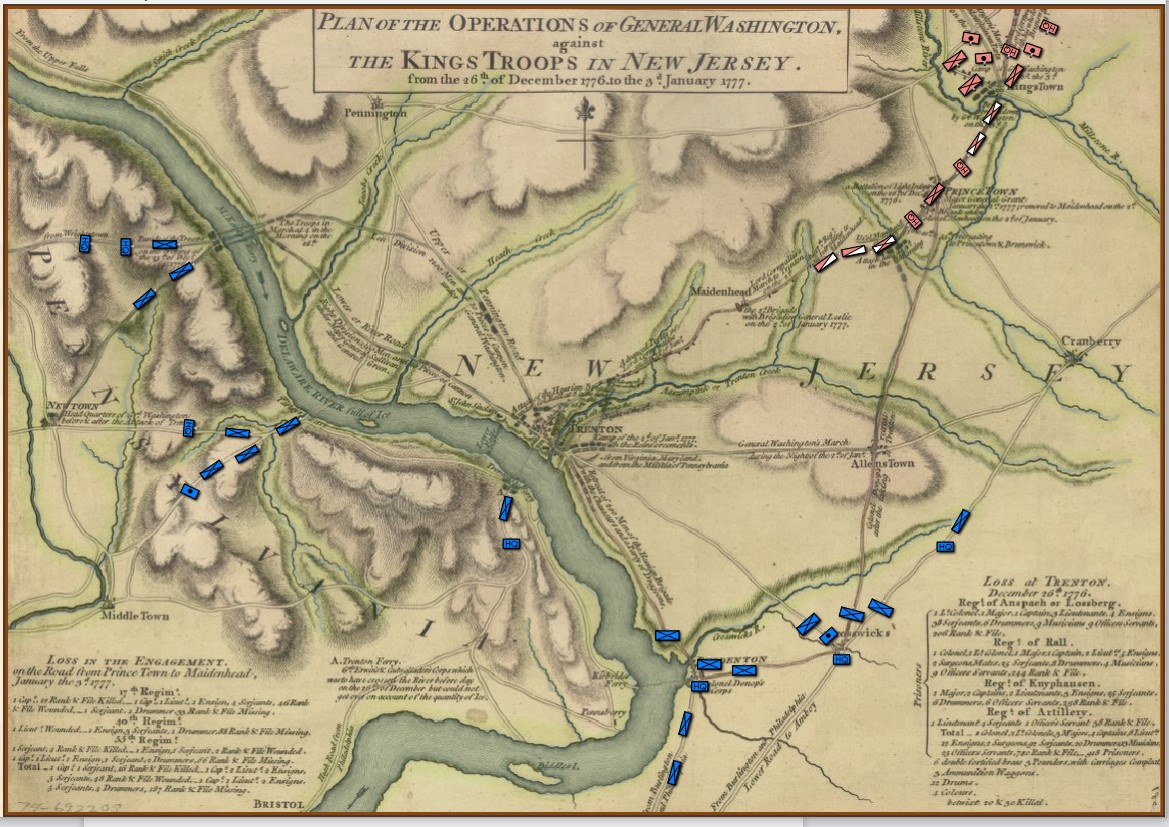

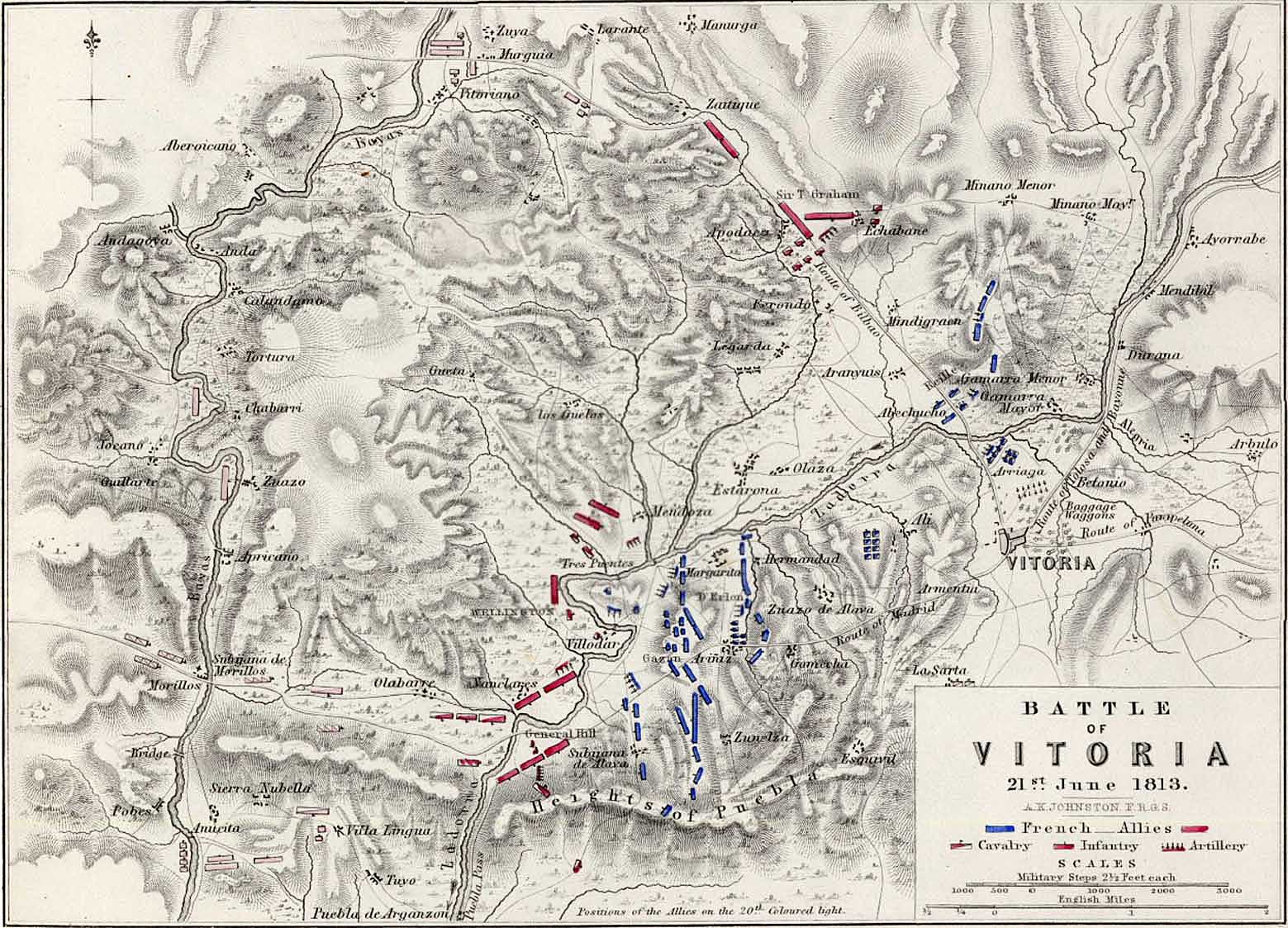

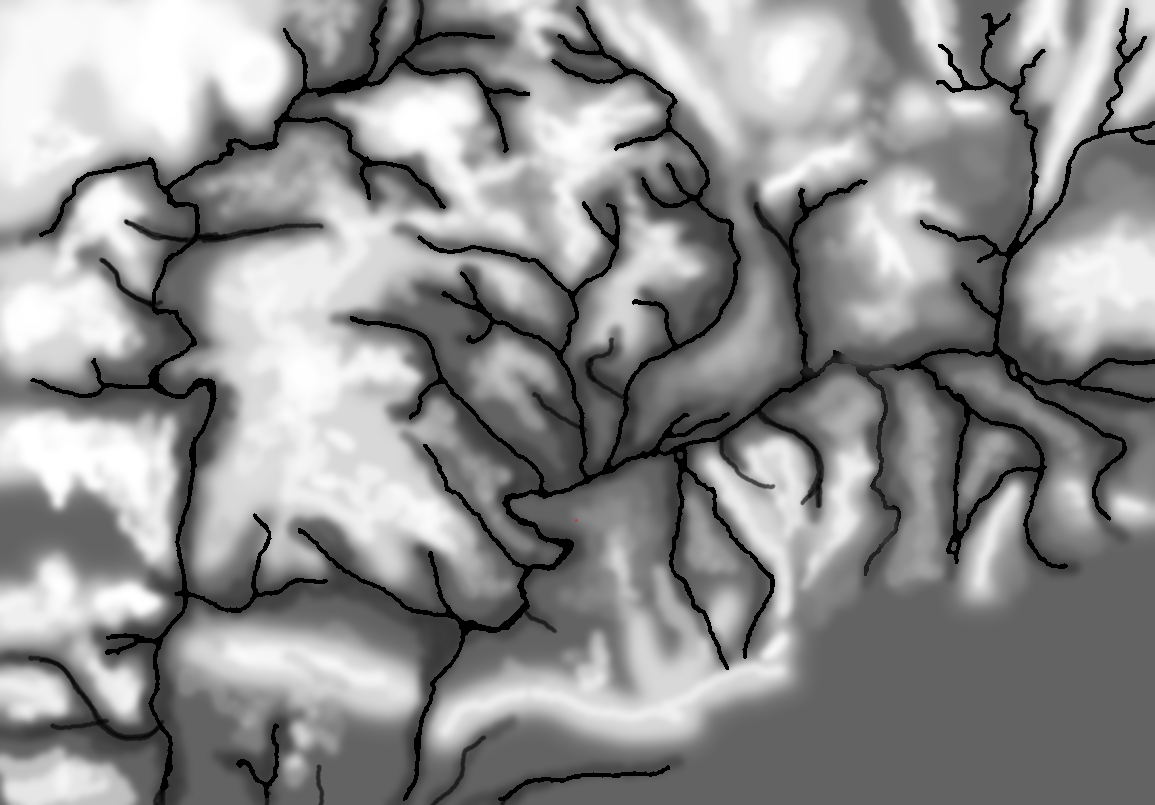

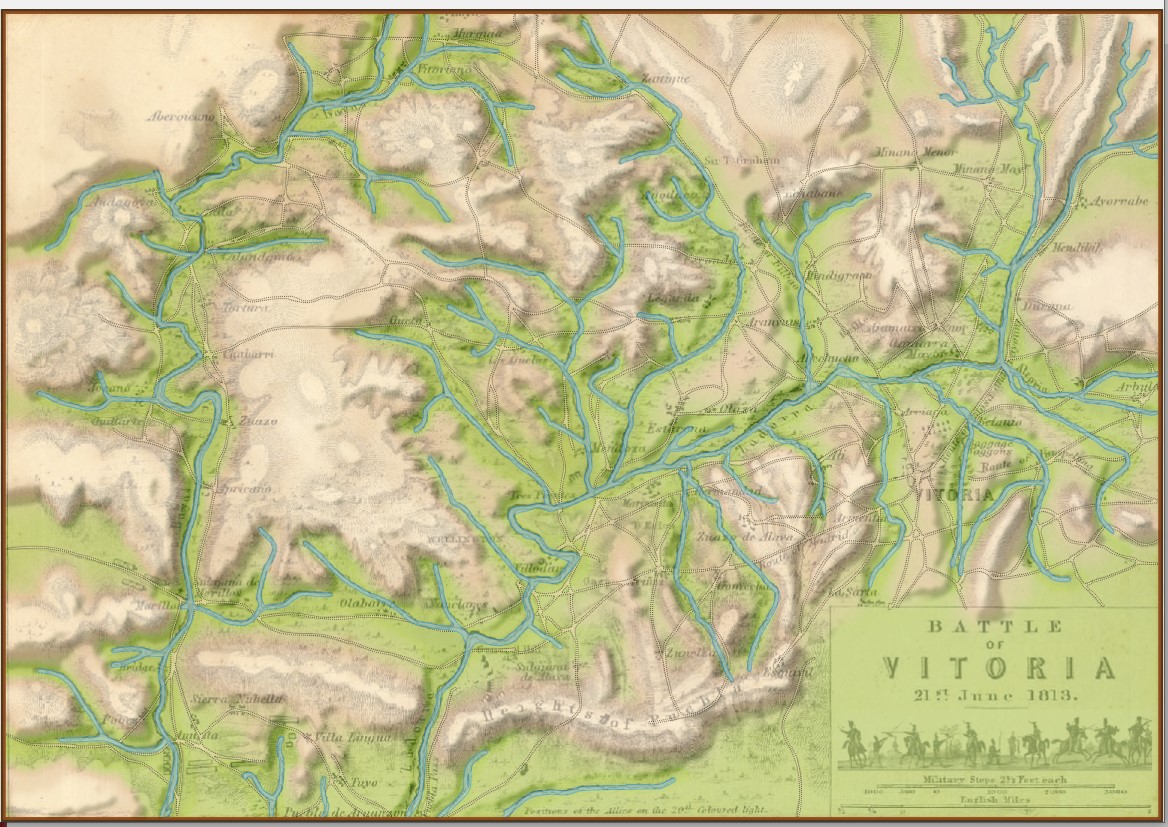

General Staff does not use hexagons or ‘zones’ of any sort. One of the failings of a system using hexes is that the entire hex has one elevation; there are no gradual slopes, just precipitous cliffs. From primary source elevation and topographical maps (like below) three-dimensional battlefields are constructed in the General Staff Map Editor (see below).

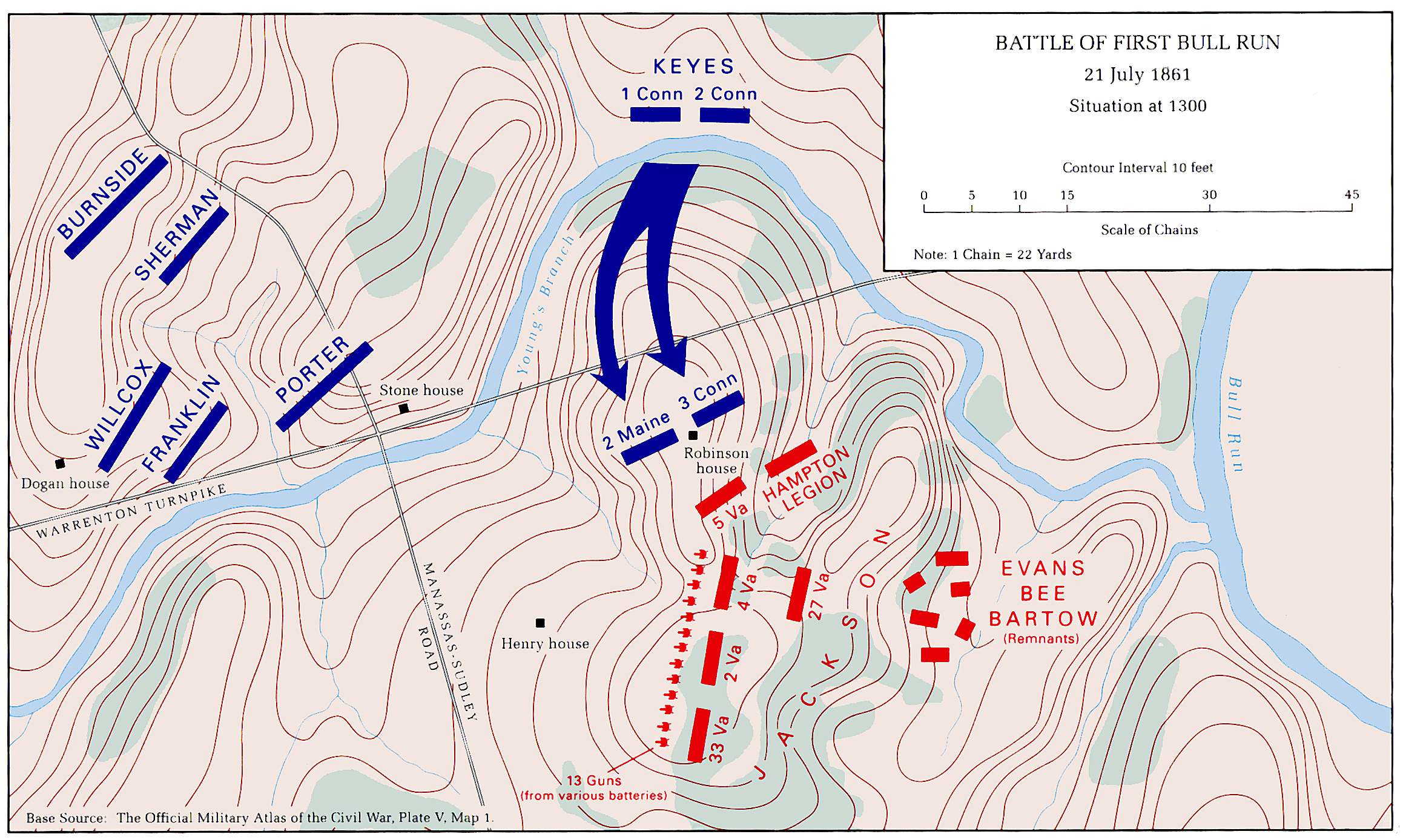

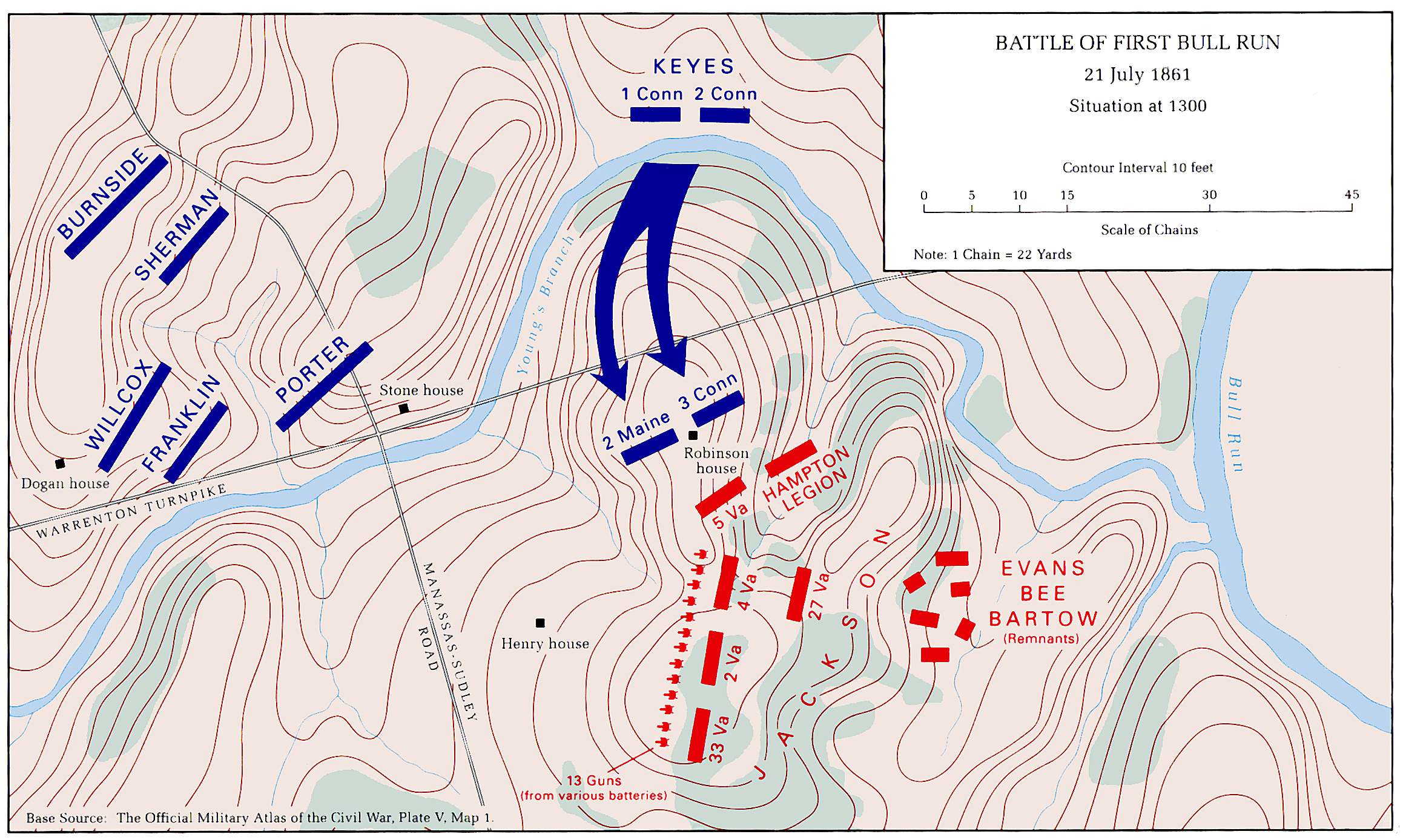

Topographical map with contour lines of Keyes’ attack at the battle of 1st Bull Run. From Wikipedia. Click to enlarge.

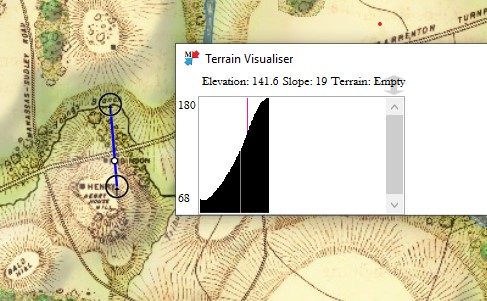

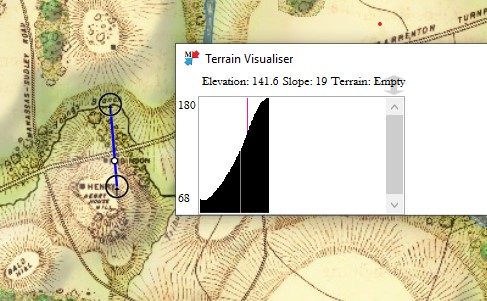

The General Staff Map Editor has a Terrain Visualizer tool (see below). It allows a line to be drawn between any two points on the map and a cross-section of the terrain and elevation to be displayed.

The area of Keyes’ attack in the General Staff Map Editor showing the cross-section Terrain Visualizer with slope calculations along the blue line drawn between the two user selected red circles. The white circle on the blue line is the current point being displayed by the vertical line in the Terrain Visualizer.

In the above image we see that the steepest part of the slope up Henry House hill is 19°. This is confirmed by the contour map, above and a photograph of the actual area below:

This panorama photographic view of the area covered by Keyes’ attack at 1st Bull Run was taken by Johnnie Jenkins December, 2020. The Robinson House was beyond the large tree, center. Click to enlarge.

As always, please feel free to contact me directly (Ezra[at]RiverviewAI.com) if you have any questions or comments.

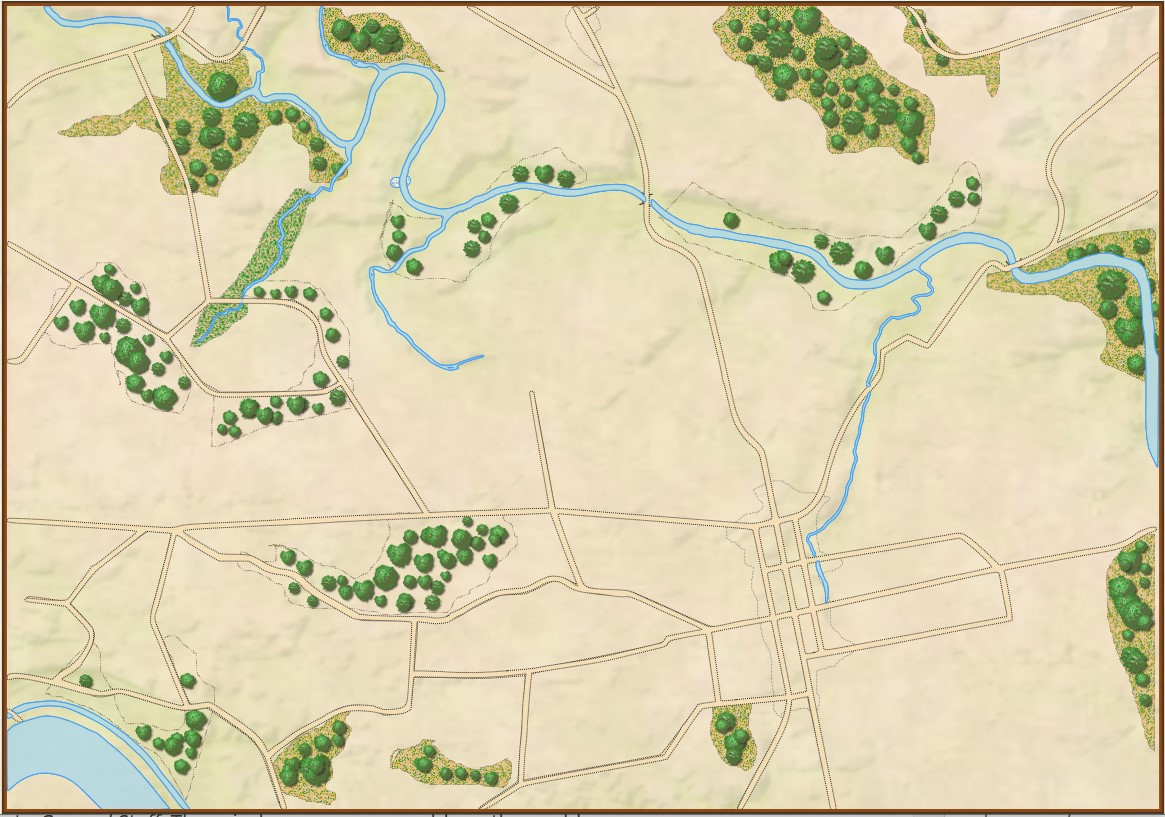

This map (above) certainly reminds me the plastic 3D maps we used to see back in grade school. I think they look fantastic. Here are some more:

This map (above) certainly reminds me the plastic 3D maps we used to see back in grade school. I think they look fantastic. Here are some more: