When I first started thinking about designing General Staff I envisioned a simple game that was almost chess-like in parts and that was designed to introduce novices to wargames. I thought that the Xbox would be the ideal platform.

After talking to two major digital wargame publishers I was told:

![]() There is absolutely no wargame market for the Xbox and it was idiotic to even think that there was.

There is absolutely no wargame market for the Xbox and it was idiotic to even think that there was.

![]() Traditional wargame buyers want more complex games; not introductory games.

Traditional wargame buyers want more complex games; not introductory games.

![]() Wargame buyers (can we just say Grognards?) still fondly remember UMS, UMS 2 and The War College (UMS 3) and would certainly support a major update.

Wargame buyers (can we just say Grognards?) still fondly remember UMS, UMS 2 and The War College (UMS 3) and would certainly support a major update.

Consequently, I have had to readjust my thinking about the gameplay and design of General Staff. Maybe the wargame you want to buy is different from the wargame that I was planning on making. To better understand what exactly customers want from General Staff I’m going to be posting a series of surveys about very specific gameplay and design issues. I’m going to lay out the pros and cons of the various options and then I’m going to ask you to please vote and give me feedback.

Simple unit details:

My original design called for a very simple unit structure. Other than a number of bookkeeping variables (such as location, facing, speed, orders, etc.) the only values that we would store were the unit’s type and strength.

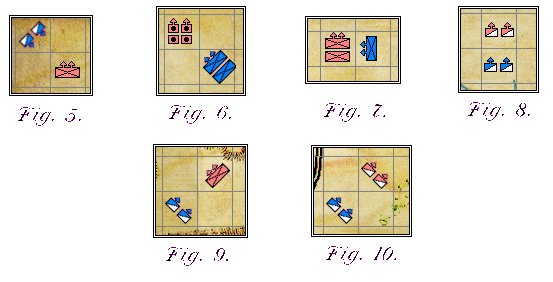

The screen captures below show examples of this design.

Screen captures of various unit types and facings in General Staff. Note that unit strength is obvious (1,2,3 or 4). Click to enlarge.

The rules on unit type and strength are:

- In any given square there can be a maximum of 4 artillery units, 3 cavalry units or 2 infantry units.

- Different unit types cannot occupy the same square.

Advantages of a Simple Unit Structure:

![]() There is a very appealing simplicity to this system. The user can immediately see the strength of forces at any location. As a unit takes losses the number of symbols displayed in the square are decremented until the unit, itself, is removed.

There is a very appealing simplicity to this system. The user can immediately see the strength of forces at any location. As a unit takes losses the number of symbols displayed in the square are decremented until the unit, itself, is removed.

![]() Less data is required to create a scenario. But, the real problem is trying to assign values to variables like ‘morale’, ‘experience’ or ‘leadership’. Inevitably, these are just value judgments.

Less data is required to create a scenario. But, the real problem is trying to assign values to variables like ‘morale’, ‘experience’ or ‘leadership’. Inevitably, these are just value judgments.

![]() It presents a simple and less intimidating interface (no names, ‘strength bars’, etc.) for beginners.

It presents a simple and less intimidating interface (no names, ‘strength bars’, etc.) for beginners.

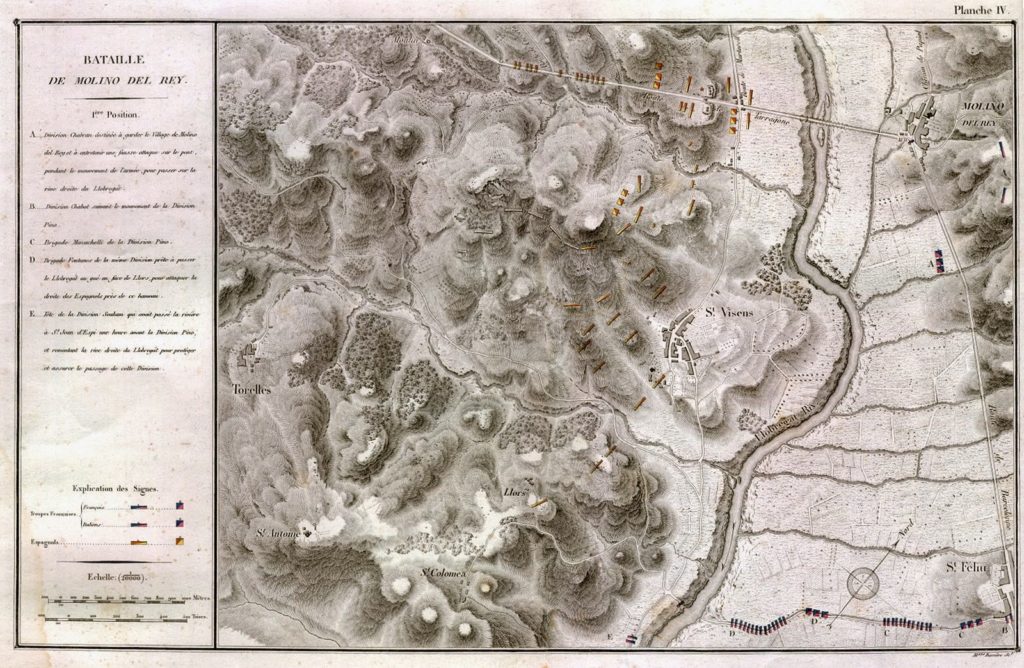

![]() Visually it fits right into the Napoleonic and Victorian topographical battlefield map engravings style that I want to emulate. I, personally, am greatly enamored by this style and would love to maneuver units on these incredible contoured maps:

Visually it fits right into the Napoleonic and Victorian topographical battlefield map engravings style that I want to emulate. I, personally, am greatly enamored by this style and would love to maneuver units on these incredible contoured maps:

Bataille de Molino del Rey : 1ere Position [y] 2éme Position (1820) .From: Biblioteca Virtual del Patrimonio Bibliográfico. A superb example of 19th century battlefield map engraving. Click to open link in new window.

Complex unit details:

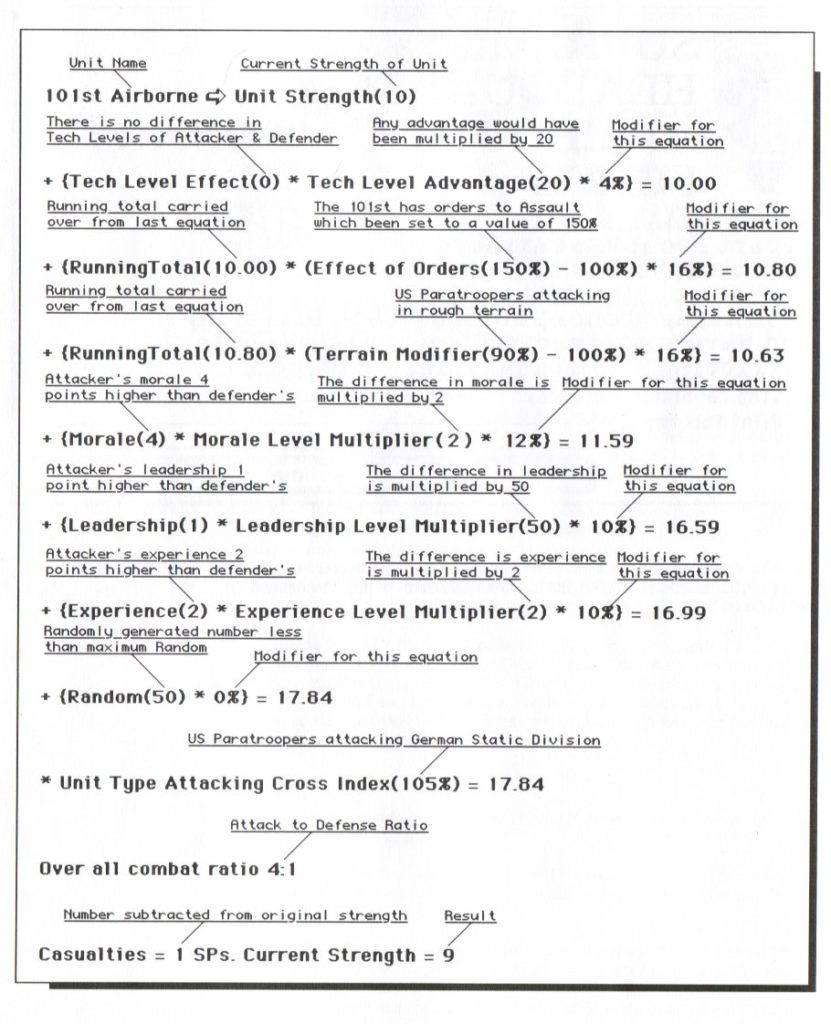

How much information can we store about every unit on the map? The only limit is the size of available storage; in other words, on modern computing devices, there are no real limits. Below is screen shot (with explanations) of the variables used to calculate combat results in UMS II: Nations at War.

Among the most likely variables to be included in the unit structure are: unit name, leadership value, morale level, strength, fatigue and unit type.

Advantages of a Complex Unit Structure:

![]() Theoretically, the more data you have the more accurate the simulation. Obviously, this depends on the accuracy of the data but as long as the variables are relevant to the simulation and your model is good, the more variables the better.

Theoretically, the more data you have the more accurate the simulation. Obviously, this depends on the accuracy of the data but as long as the variables are relevant to the simulation and your model is good, the more variables the better.

![]() Simply having a more detailed model with a lot of unit variables may help to sell more units to Grognards.

Simply having a more detailed model with a lot of unit variables may help to sell more units to Grognards.

Disadvantages of a Complex Unit Structure:

![]() More data has to be researched, compiled and entered into the Create Army Module (see here).

More data has to be researched, compiled and entered into the Create Army Module (see here).

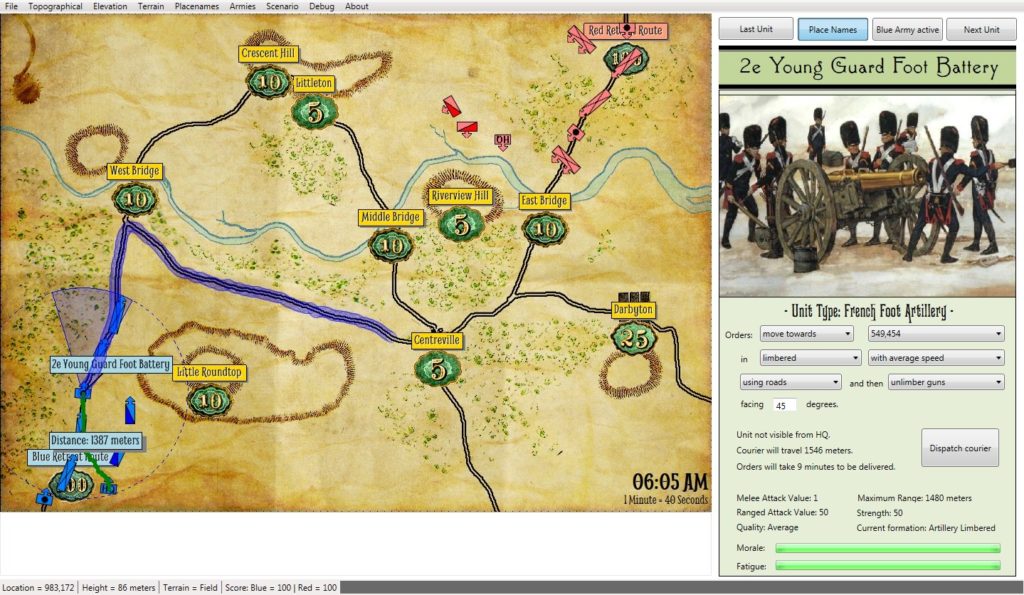

![]() This data needs to be displayed in a way that doesn’t overload the user. Below is a screen shot of some tests that I did for an earlier version of General Staff:

This data needs to be displayed in a way that doesn’t overload the user. Below is a screen shot of some tests that I did for an earlier version of General Staff:

Screen capture showing one method of displaying information about a unit. In this case the stored values include Melee attack value, maximum range, ranged attack value, strength, unit quality, formation, morale and fatigue. Click to enlarge.

![]() Inevitably, at some point the scenario designer has to make some very arbitrary decisions about a unit’s morale and leadership values.

Inevitably, at some point the scenario designer has to make some very arbitrary decisions about a unit’s morale and leadership values.

![]() What is the maximum strength of a unit? Remember we’re talking apples (artillery) and oranges (infantry divisions) here. What does the value ‘strength’ actually mean? Is it the number of men in the unit? Clearly 50 men in an artillery battery have more ‘strength’ than 50 men in a line infantry company. Is there some other modifier (perhaps ‘unit type’) that is necessary to convert a unit’s strength to its combat power? And, what if a scenario designer creates a unit with a strength of 1,000 while other units have values of, say, 10? Will this be an unstoppable behemoth on the battlefield?

What is the maximum strength of a unit? Remember we’re talking apples (artillery) and oranges (infantry divisions) here. What does the value ‘strength’ actually mean? Is it the number of men in the unit? Clearly 50 men in an artillery battery have more ‘strength’ than 50 men in a line infantry company. Is there some other modifier (perhaps ‘unit type’) that is necessary to convert a unit’s strength to its combat power? And, what if a scenario designer creates a unit with a strength of 1,000 while other units have values of, say, 10? Will this be an unstoppable behemoth on the battlefield?

So, now it’s time for you to make your feelings known about these issues. Simple or complex unit data structures? What information should be stored about each unit?

[os-widget path=”/drezrasidran/gameplay-1-unit-complexity” of=”drezrasidran” comments=”false”]

You input is very important to us. Please feel free to give us more feedback either via the online form or by emailing me personally at Ezra [at] RiverviewAI.com

I couldn’t answer the survey question as it really depends on the period you are trying model and the level of command the player assumes. If its 18th or 19th century then only vague, general numbers would be available. While 20th and 21st century commander would have more at hand due to better communications. In general, a brigade commander would have far more information concerning his battalions than an army commander. This would likely be true for any period. Information can flow upward, but that flow would need to be initiated from the top and would not reflect up to the minute accuracy.

Again, unless you are contemplating a 21st century battle, perfect information concerning the position of friendly and enemy troops would never be available. This information can flow upwards but would be, by necessity somewhat out of date due to transmission time. This was always the Achilles heel of miniature gaming.

I suppose the first thing you need to decide is what period you are trying to recreate and also what type of game you want. Do you envision a computerized recreation of the SSI games, where everything concerning the both enemy and friendly units are known? Or do you want a to make a game that recreates the fog of war, so important in real battles, that can be found found in modern games such as SOW?

I certainly should have made this clearer. For this wargame I want to model 18th and 19th century. However, I plan on using the same engine for Ancients and a Modern wargame as well.

Thanks for the feedback!

Dr. Sidran, Mr. Isenberg et al.

GMT games has recently been making more of a push into the computer market with their board game conversions (see Twilight Struggle), Gene Billingsly is very open to helpful advice to game designers and would be another person to sound out with your game design.

Regarding the issue of complexity. Many wargames that appeal to the grognard (OCS system, ASL etc.) have very intricate rules which definitely cry out for a computer system to deal with the complexities of the logistics, supply, troops condition, weather etc. Some PC games do this quite well (Gary Grigsby’s War in the East/West) by making a chit show the basic information and allowing you to click on it to gather more precise information as to its condition. The simplicity level can be taken too far the other way though when you look at Paradox’s Hearts of Iron IV and compare the dearth of information available compared to Hearts of Iron III, in an attempt to broaden their appeal and player base, and ending up pleasing no one.

The old Kriegsspiel game that is available from Too Fat Lardies based on Von Reisswitz’s original rule set, has on the other hand a display system, which you say you desire to emulate, and in reality the barest of tables for looking up results. The enjoyment comes, after running a couple of games, is in the double blind aspect and the players trying to peer into the future not knowing what the umpire is going to determine is happening until it happens, where the enemy truly is or even if their own forces are where they have been told they are from a courier that took 30 minutes to relay a SPOTREP. The enjoyment is all the greater for the player if he only receives intermittent messengers updating him to his troops status so he can concentrate on directing his forces in the field. All the details are being processed behind closed doors by an umpire, much as a computer would do.

The conflict time period would have a consideration here as well. The more modern the conflict, the more information will be expected from the player.

In Summary: Pieces don’t have to be fantastically detailed, as computers allow you to click/hover on them to gather more detail.

The game should have complexity either built into it or brought out of it in a fog of war system which allows the player the intellectual exercise of learning the game and what advantages he can wring out of it.

Offload as much of the complexity as you can into the core processor but allow the spreadsheet of information to be accessible as needed.

looking forward to following your future progress

Thank you so much for your comments! I will certainly take them to heart.

I would echo Brett’s comments.

I’m not sure I agree with the XBOX info. Is it a matter of the chicken and the egg? Or a matter of having an engaging game that people can play using a controller. Depending on the development environment, I’d think one could add a version for XBOX without creating an entirely new build. If it could be done with a minimal amount of effort it would at least help drive traffic to the game. Maybe John Tillers style of games wouldn’t translate well to the XBOX, but maybe another style of game would?

I think the big problem at this point is that Microsoft no longer has the XBox Indie Live channel for independent games. Consequently, to release a game for the XBox now entails going through Microsoft. I’m not sure if this is possible for a small developer.

Ahh, I wasn’t aware that they dropped that channel. Going direct through Microsoft would be a tougher issue. I’d agree with Mr. Bayley’s comment below as well. I can jump into a quick game of War in the East, where to do the same thing with the OCS system would take an evening just to setup.

Automate the fiddly stuff and accentuate the cool stuff.

Yes, the XBox Indie Live channel was dropped in November, 2016.