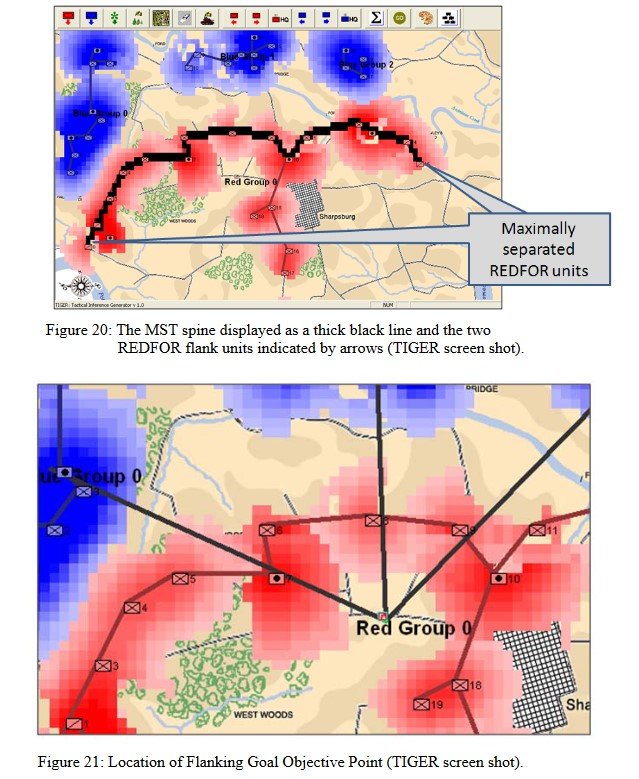

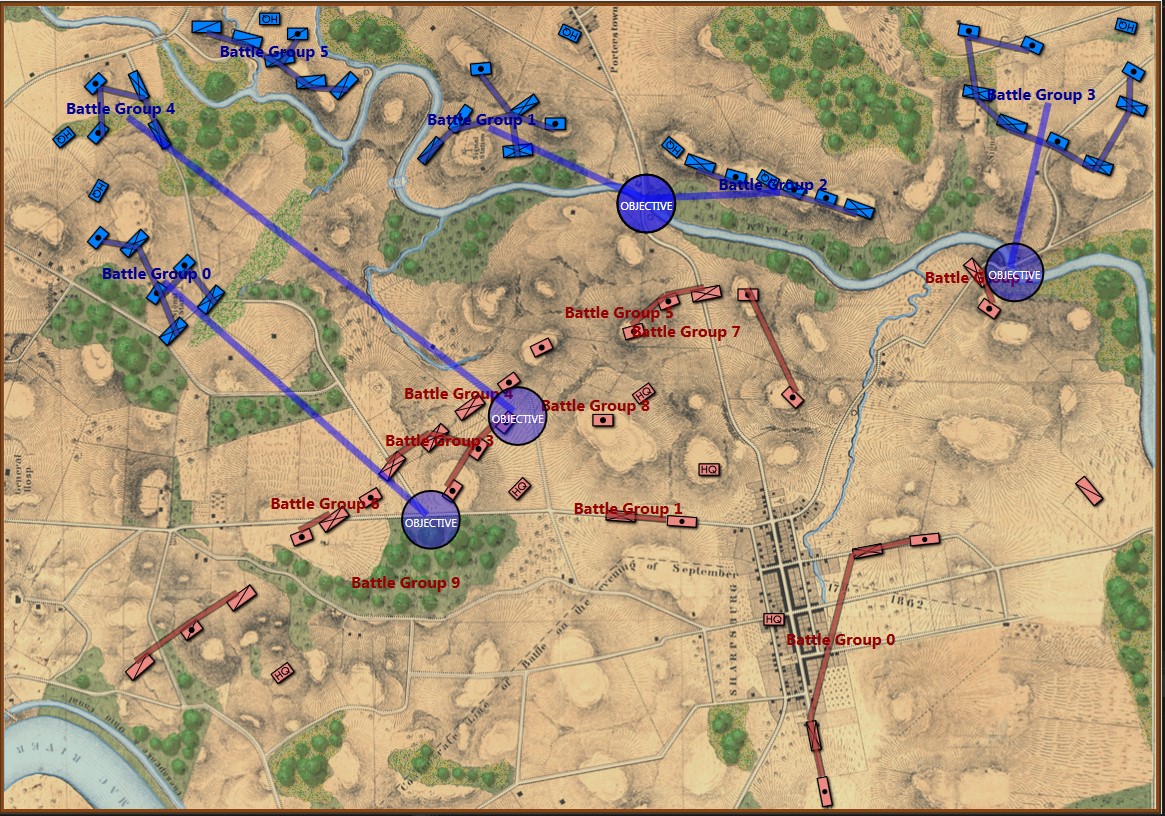

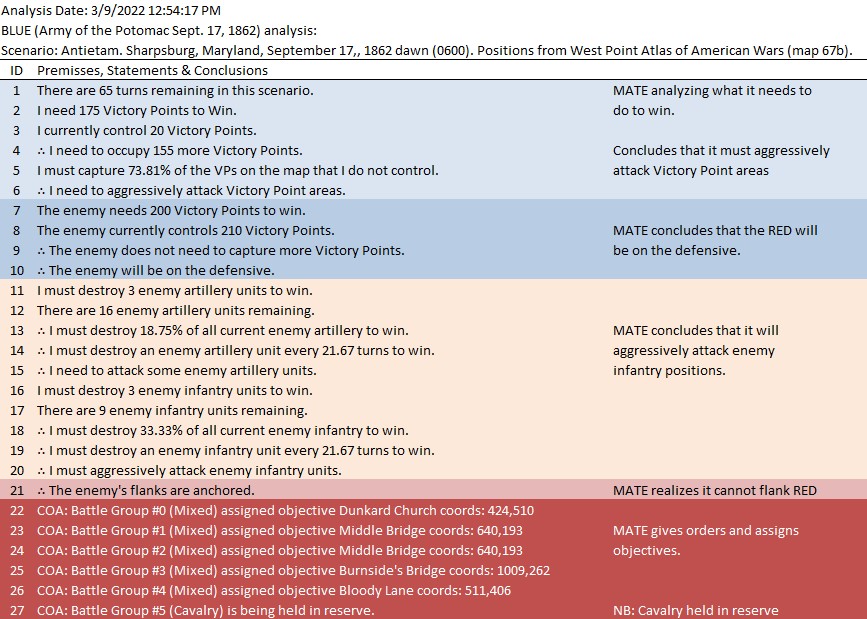

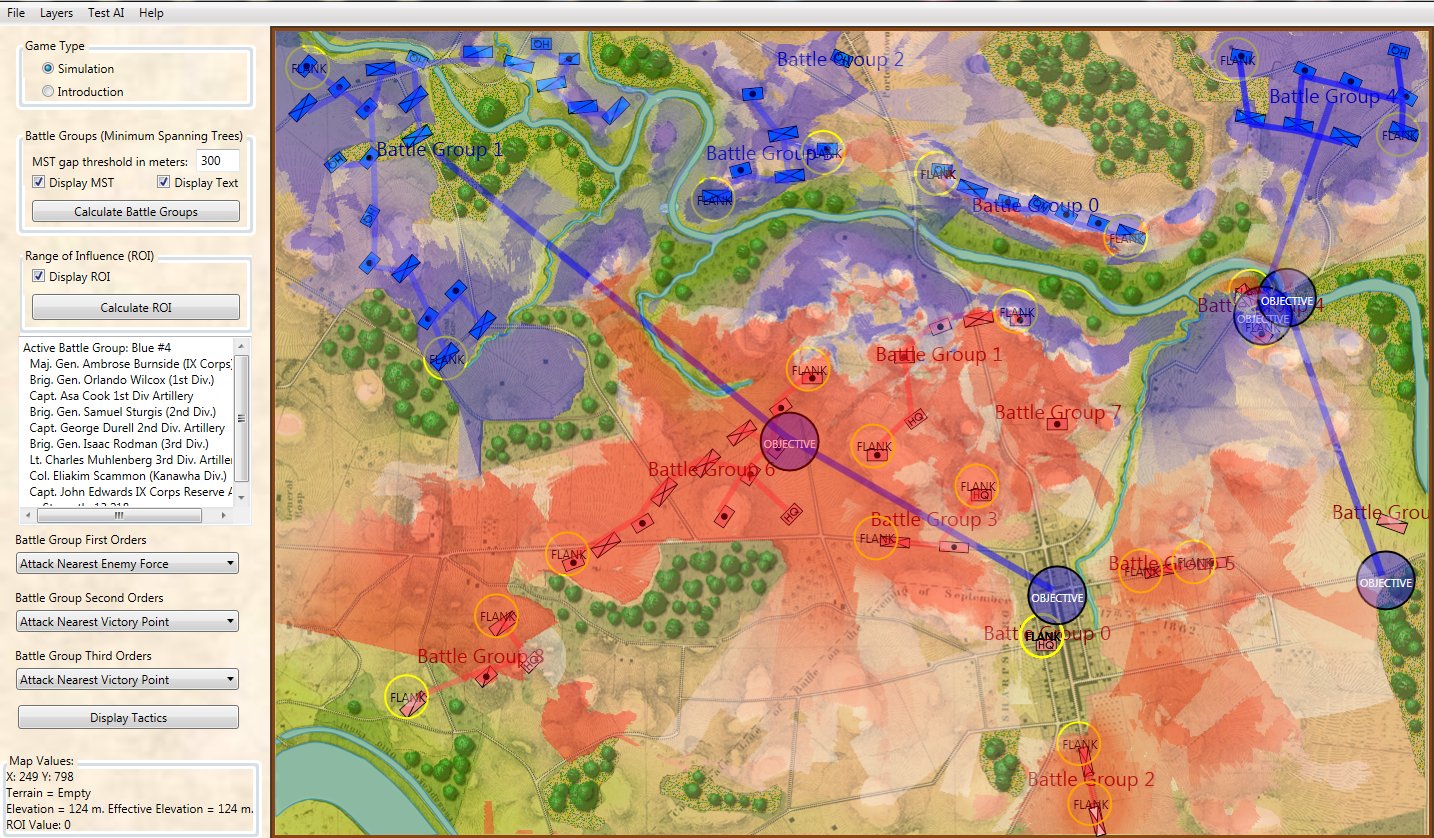

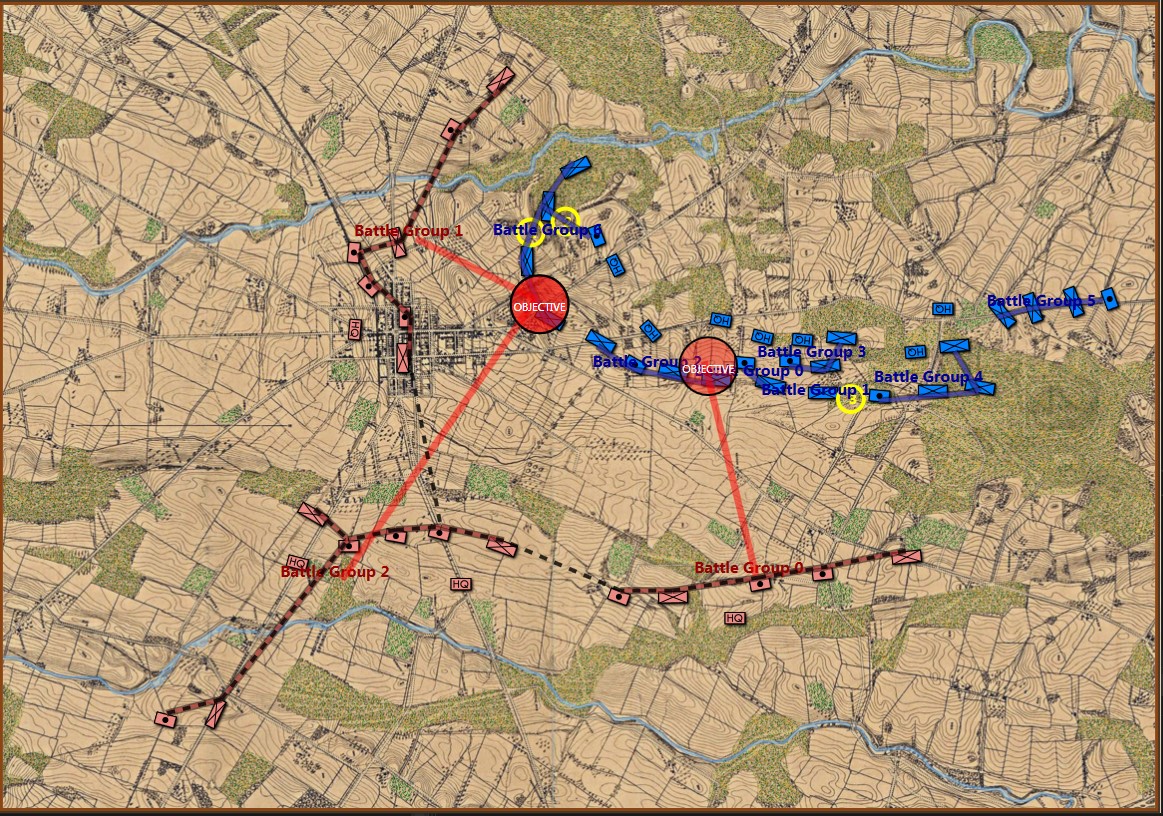

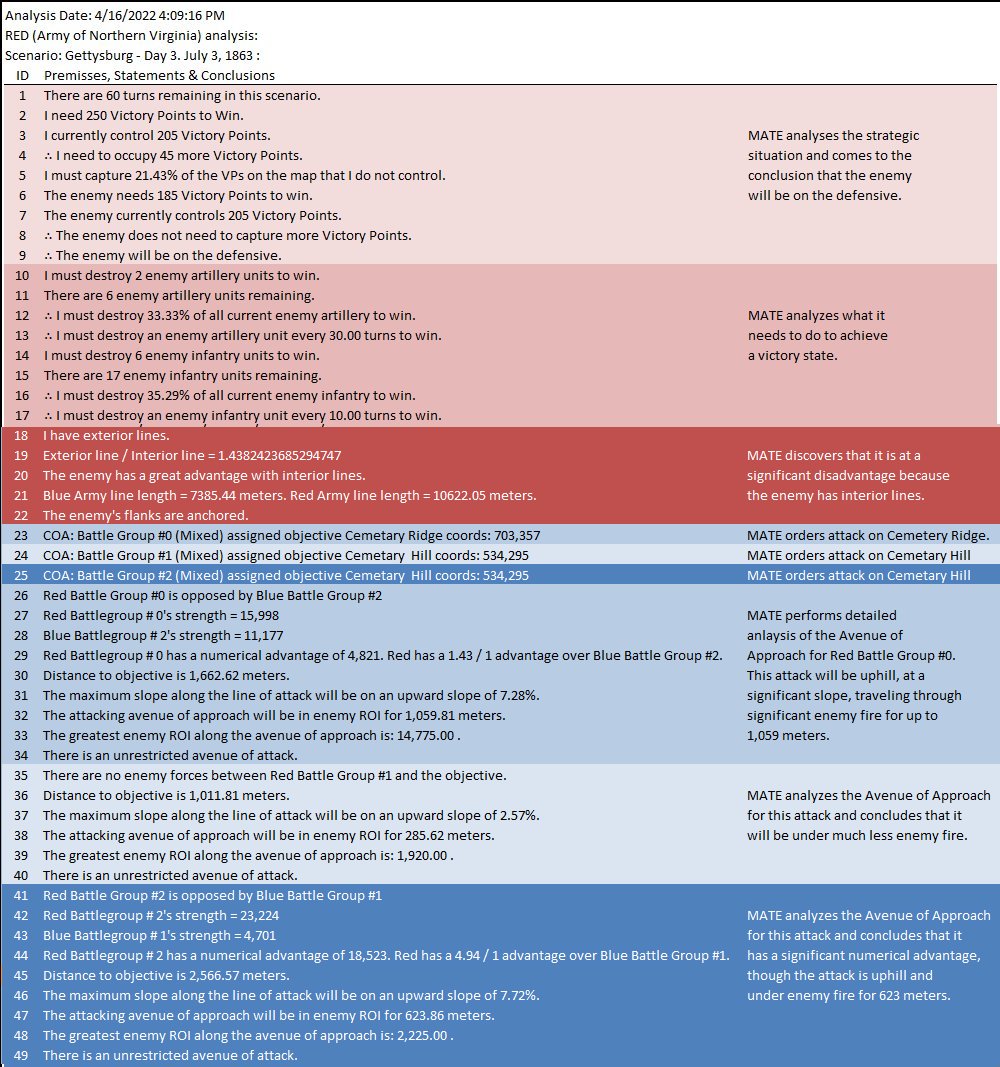

Screenshot of MATE analysis of Gettysburg, Day 3 from the Red (Confederate) position. Click to enlarge.,

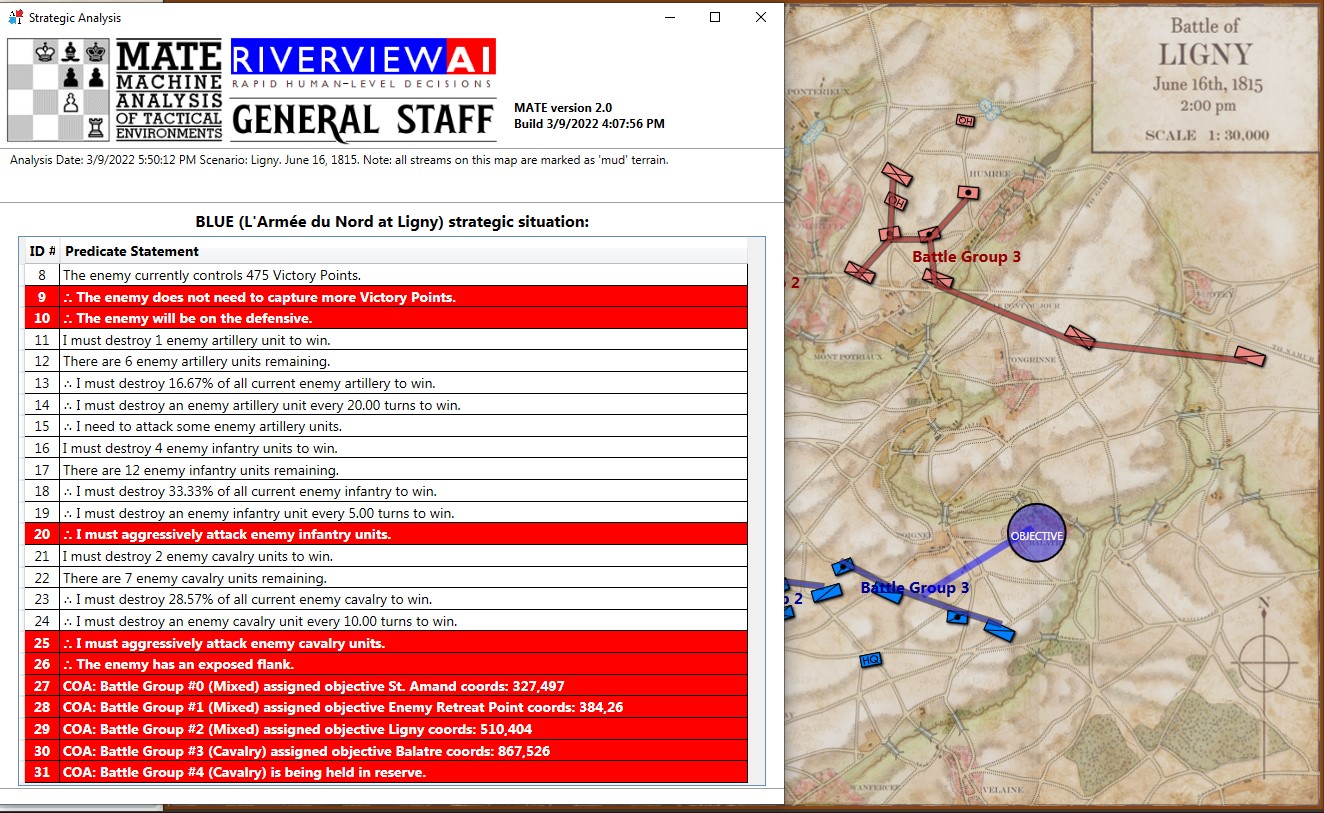

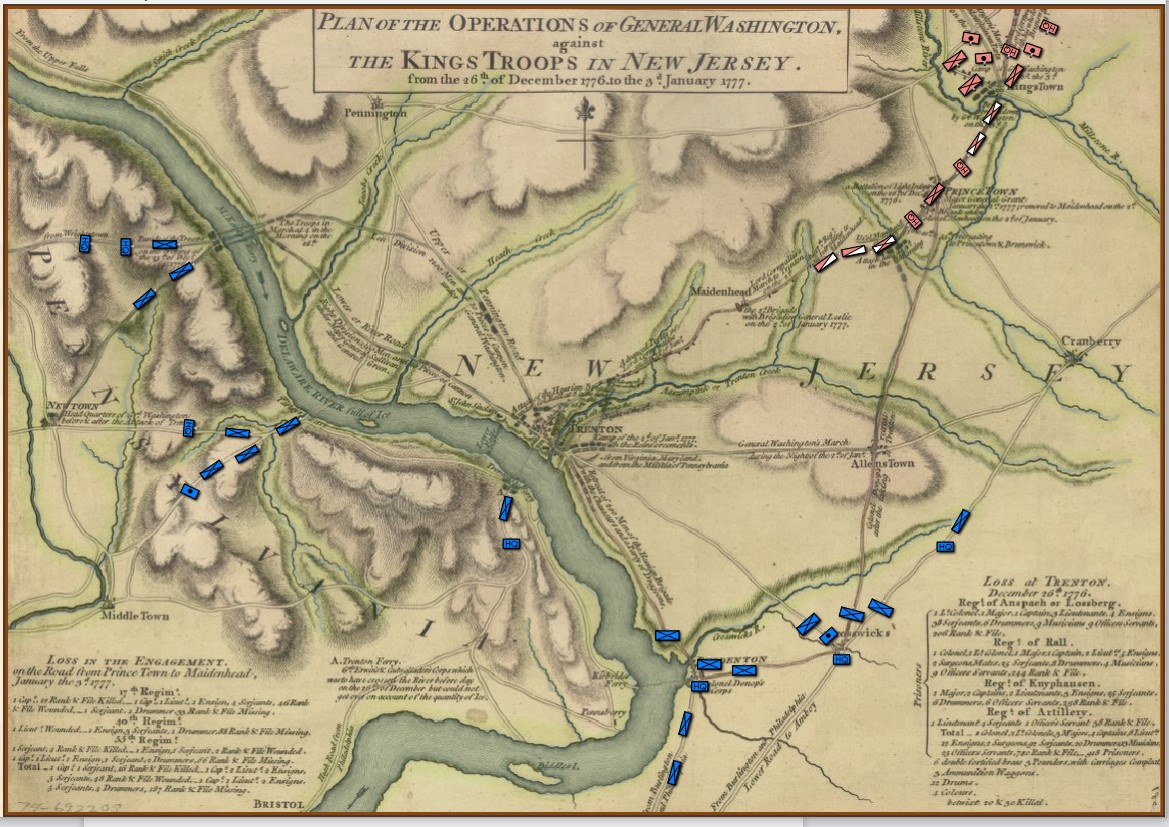

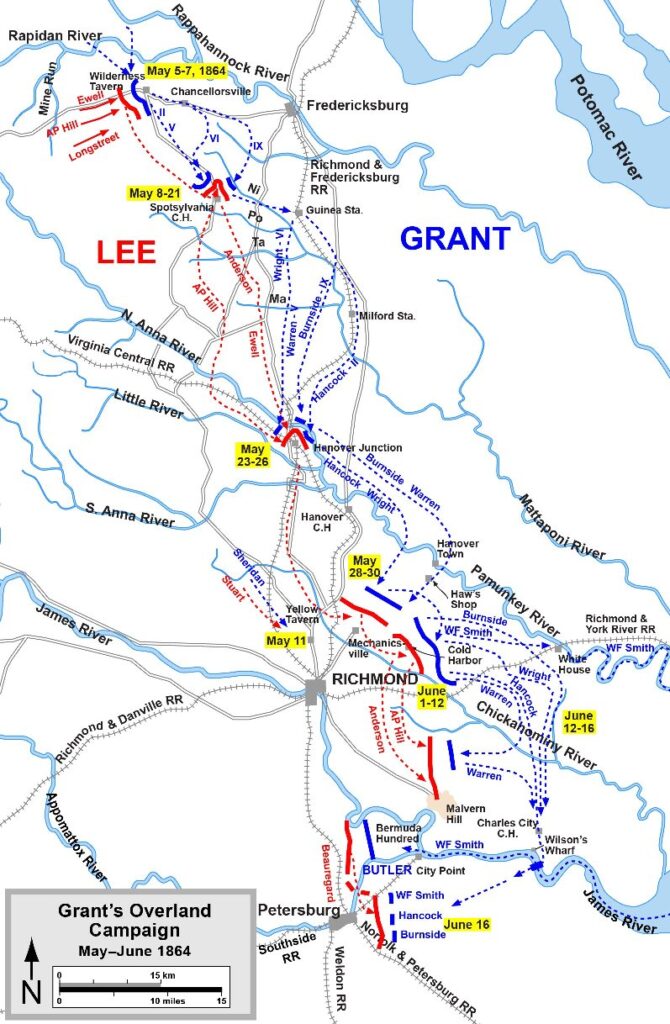

General Lee, at Gettysburg, said: “the enemy have the advantage of us in a shorter and inside line and we are too much extended.” – quoted by Major General Isaac Trimble.1)Isaac Trimble, Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 26, Richmond, Virginia: Reverend J. William Jones, D.D., MATE, the AI behind General Staff, came to the exact same conclusion:

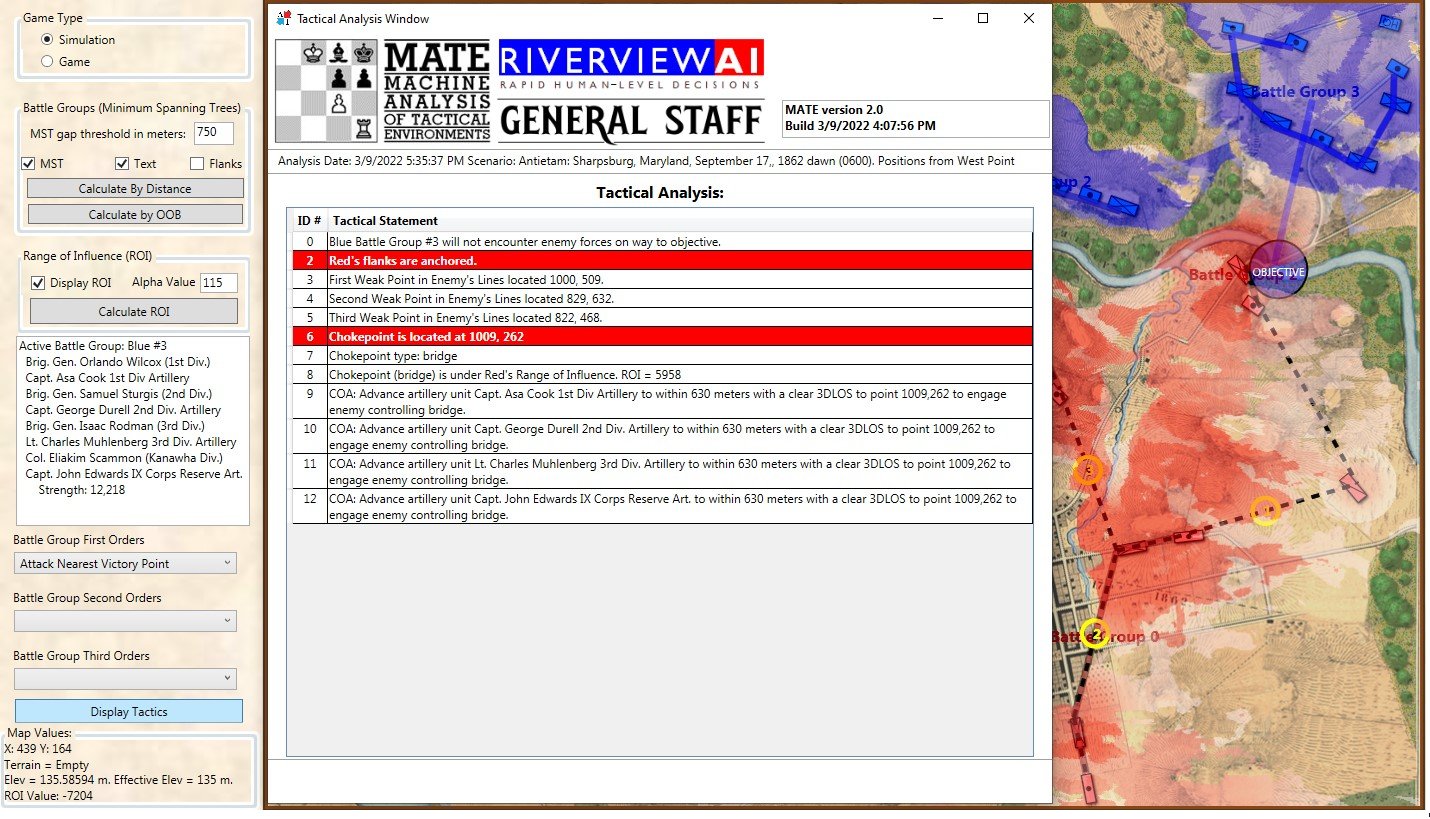

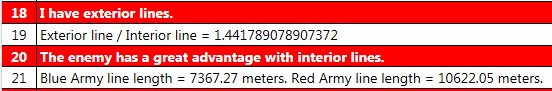

A portion of MATE’s analysis of Red’s position at Gettysburg, Day 3. Here MATE recognizes that Red has exterior lines and the enemy has a decided advantage.

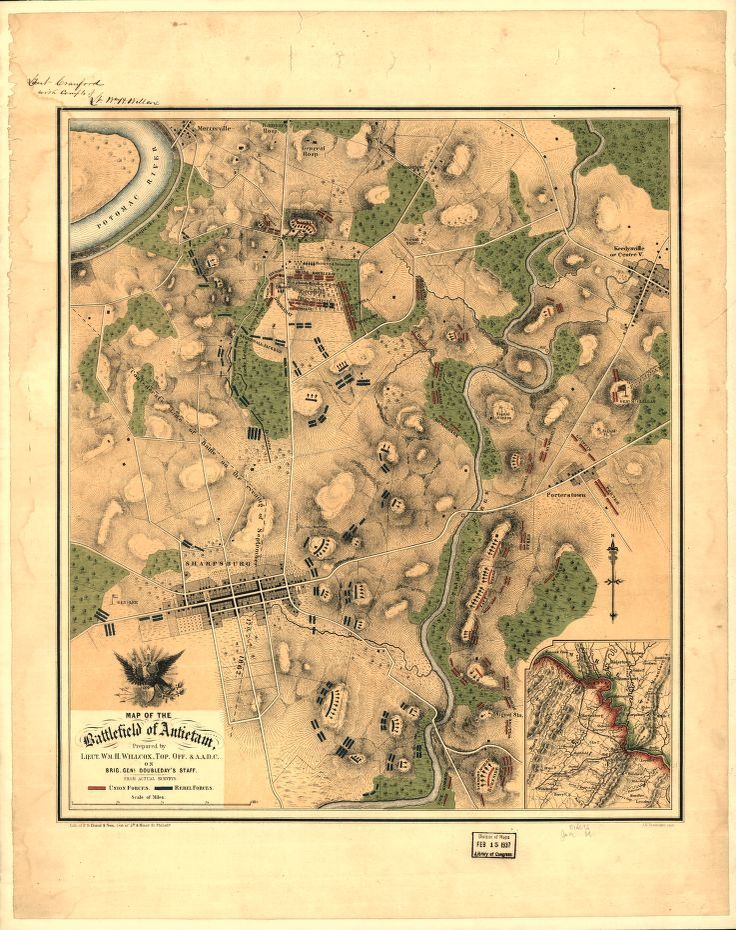

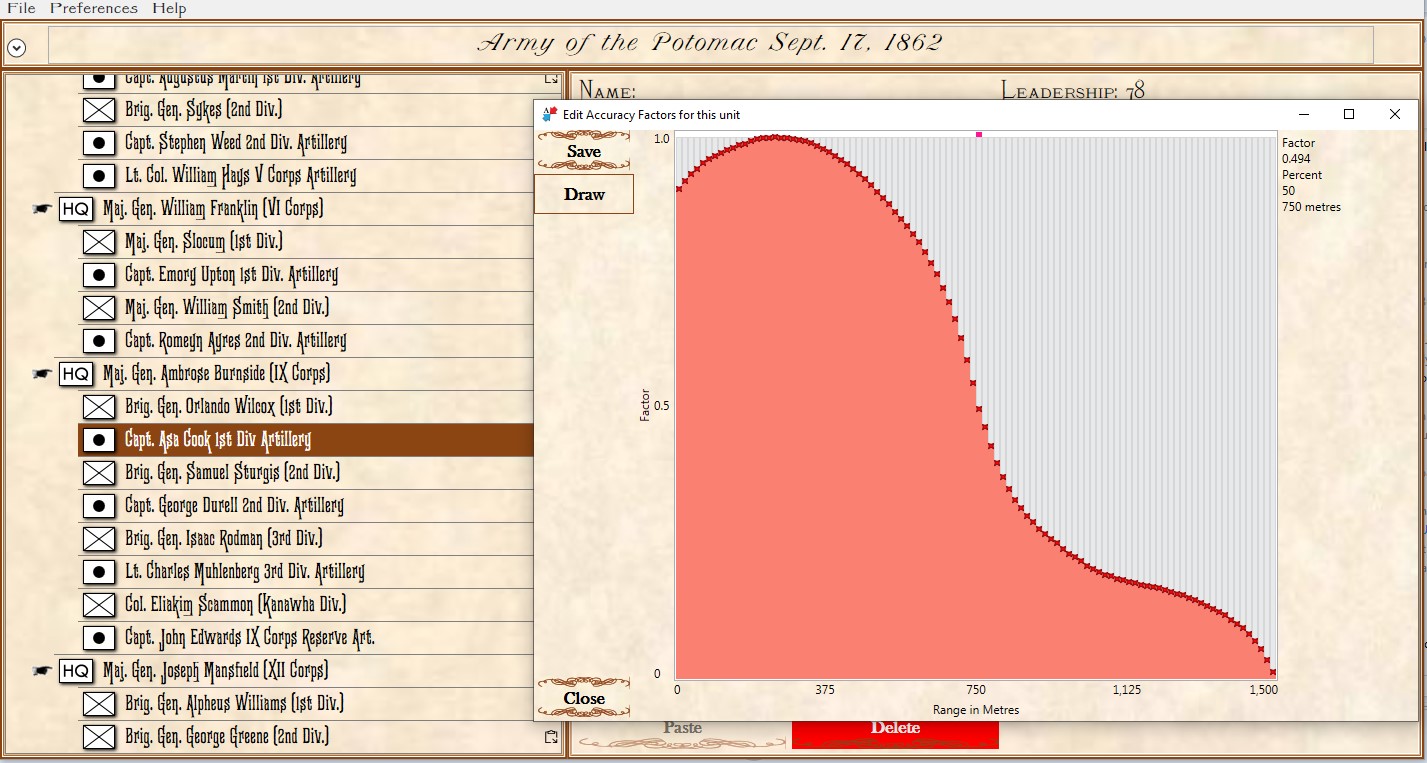

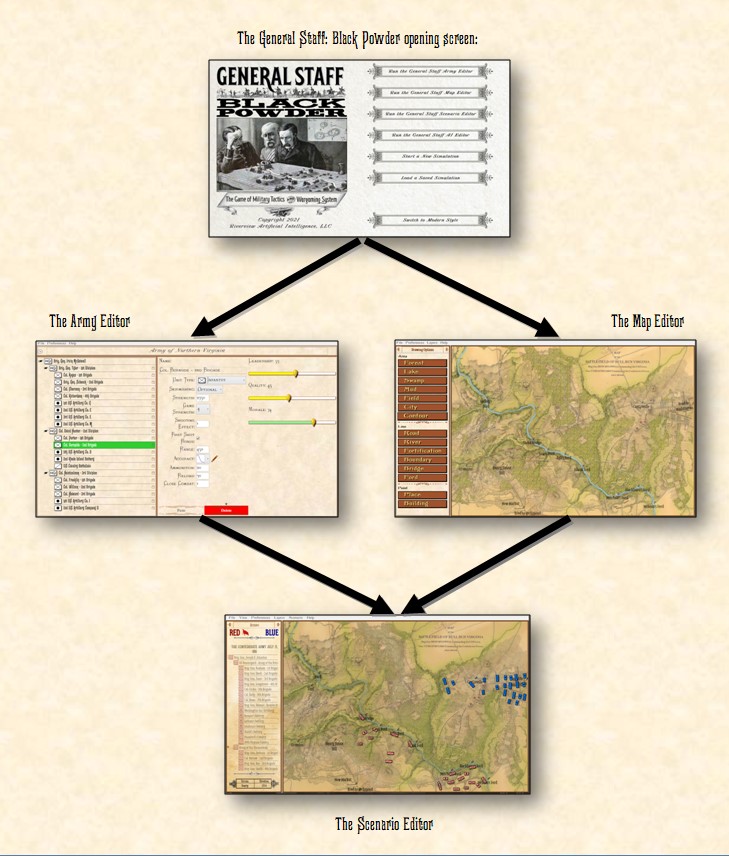

I have been porting TIGER 2)Tactical Inference GenERator, the AI behind my doctoral thesis and my DARPA sponsored research from C++ to C# and integrating it into the General Staff: Black Powder wargaming system. I have been doing this via the method of first creating a scenario typifying a specific attribute (exterior lines, exposed flanks, choke points, etc.) and then porting the actual code over and feeding it the scenario for analysis. Gettysburg, Day 3, is the canonical example of exterior and interior lines.

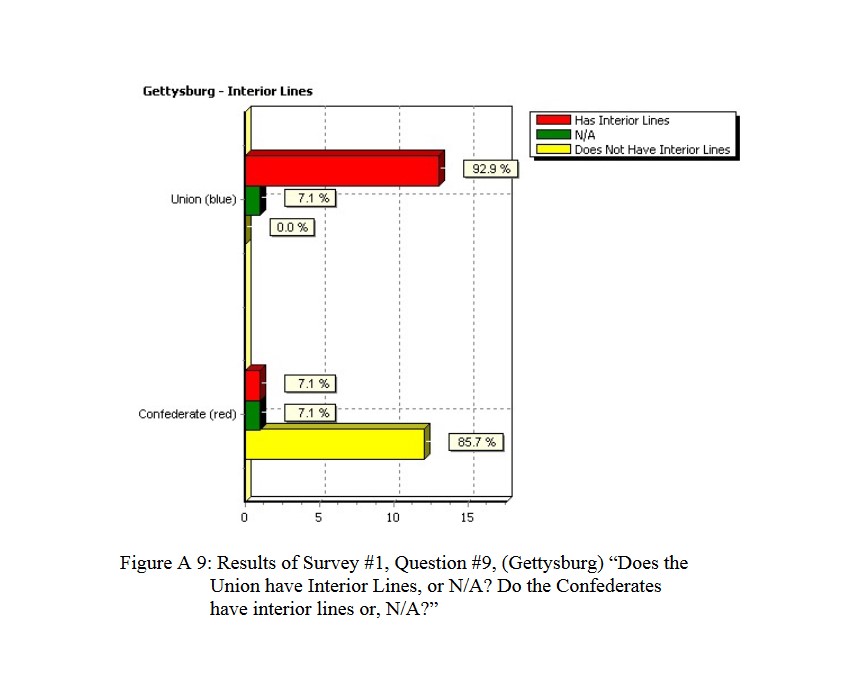

92.9% of Subject Matter Experts agree! The Union (Blue) lines at Gettysburg, Day 3, exhibit the attribute of being Interior Lines. Interior lines are good. Exterior lines are bad. From author’s doctoral thesis.

So, first a significant number of Subject Matter Experts (combat commanders, tactics instructors at military academies, etc.,) agree that there is an attribute called ‘Interior Lines’ and that it is exhibited by the Union (Blue) forces at Gettysburg, Day 3. We then create an algorithm that can detect such an attribute and convert it from C++ code to C# code (and substantially rewrite and improve said algorithm in the process) . We then create a Gettysburg, Day 3 scenario using the General Staff Army Editor, the General Staff Map Editor and the General Staff Scenario Editor and feed the scenario3)In Computer Science lingo programs are machines that consume data / tokens to MATE, the General Staff: Black Powder AI. These are the results:

MATE analysis text output (with author’s commentary) of Gettysburg, Day 3, from the Red (Confederate) position. Click to enlarge.

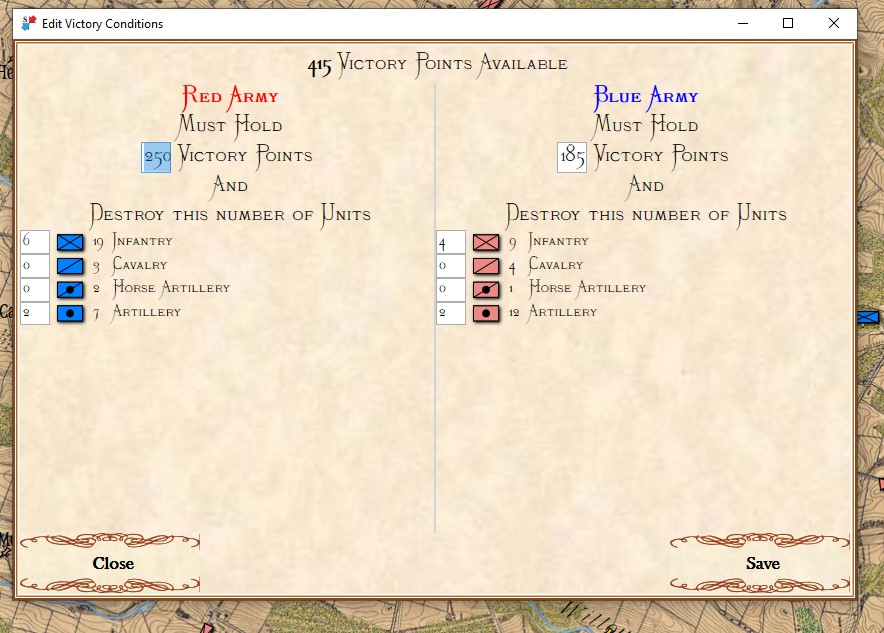

The first time that I presented the Gettysburg, Day 3 scenario as Red to MATE it refused to attack. The enemy has interior lines (1.4, or 40% greater is pretty significant value), you’re attacking uphill (slope > 7%), your attacking units are under enemy ROI (mostly batteries of 12 lb. Napoleon canon shooting explosive shot and then canister and then double-shotted canister) for over a kilometer. Attacking is not a good idea. To get MATE to attack I had to go back to the Map Editor and create a number of new Victory Points; specifically the places where significant roads (Emmitsburg Road, Cashtown Road, Baltimore Pike, etc.) enter the map. Then I went in to the Scenario Editor and assigned appropriate values and current ‘ownership’. Saved it all and fed it back to MATE and the, above, is what I got.

The only way for MATE to win (as Red) is to attack large Victory Point areas (Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge) and hope to destroy significant numbers of Blue (Union) forces along the way to meet the victory conditions set in the Scenario Editor:

Anybody who has built a wargame scenario (and I suspect there are more than a few among the readers of this blog) know the drill of going back to edit the OOBs, starting positions, victory conditions, etc. I would just like to say it’s pretty painless using the General Staff Wargaming System. The various editors all integrate seamlessly like Microsoft Office products (they were written in Microsoft WPF by Andy O’Neill who is a Microsoft Gold Developer).

But, the real question that this raises is: why did Lee attack on Gettysburg, Day 3? Blue (the Union) not only had interior lines, an elevated position, but they also had anchored flanks (see #22 above). MATE is running out of options at this point. If you look at the top screenshot you will see yellow numbers in yellow circles. These represent MATE’s three ‘weakest points’ in Blue’s line and it’s not much.

So why did Lee attack?

James Longstreet’s From Manassas to Appomattox states absolutely that

All that I could ask was that the policy of the campaign [Lee’s invasion of the north] should be one of defensive tactics, that we should work so as to force the enemy to attack us, in such good position as we might find in his own country, so well adapted to that purpose, – which might assure us of a grand triumph. To this he readily assented as an important and material adjunct to his general plan. [p. 331]

So, Longstreet, in his autobiography, is saying that Lee agreed that at some point in Pennsylvania, the Army of Northern Virginia would find a good solid defensive position and let Hooker (they didn’t yet know that Meade was the new commander of the Army of the Potomac) smash his army to pieces upon it. James McPherson in, To Conquer a Peace: Lee’s Goals in the Gettysburg Campaign writes:

“In a conversation with General Isaac Trimble on June 27, when most of the Army of Northern Virginia was at Chambersburg, Pa., and when Lee believed the enemy was still south of the Potomac, he told Trimble: “When they hear where we are, they will make forced marches…probably through Frederick, broken down with hunger and hard marching, strung out on a long line and much demoralized, when they come into Pennsylvania. I shall throw an overwhelming force on their advance, crush it, follow up the success, drive one corps back on another, and by successive repulses and surprises, before they can concentrate, create a panic and virtually destroy the army.” Then “the war will be over and we shall achieve the recognition of our independence.”

The argument is that Lee, on the morning of July 3, 1863, found himself in a terrible strategic situation with very few options. It was imperative that Lee must, “destroy the [enemy] army;” nothing less than a great triumph in enemy territory would do. In Lee’s only official report of the battle of Gettysburg, written on July 31, 1863 he states:

The enemy was driven through Gettysburg with heavy loss, including about 5,000 prisoners and several pieces of artillery. He retired to a high range of hills south and east of the town. The attack was not pressed that afternoon, the enemy’s force being unknown, and it being considered advisable to await the arrival of the rest of our troops. Orders were sent back to hasten their march, and, in the meantime, every effort was made to ascertain the numbers and position of the enemy, and find the most favorable point of attack. It had not been intended to fight a general battle at such a distance from our base, unless attacked by the enemy, but, finding ourselves unexpectedly confronted by the Federal Army, it became a matter of difficulty to withdraw through the mountains with our large trains. At the same time, the country was unfavorable for collecting supplies while in the presence of the enemy’s main body, as he was enabled to restrain our foraging parties by occupying the passes of the mountains with regular and local troops. A battle thus became in a measure, unavoidable. Encouraged by the successful issue of the engagement of the first day, and in view of the valuable results that would ensue from the defeat of the army of General Meade, it was thought advisable to renew the attack. . . .

Lee was in for a penny and in for a pound. This was not the defensive battle of Longstreet’s choosing. This was now Lee desperately trying to, “throw an overwhelming force on their advance, crush it, follow up the success, drive one corps back on another, and by successive repulses and surprises, before they can concentrate, create a panic and virtually destroy the army,” but now the enemy had, “retired to a high range of hills south and east of the town.” The Union had flipped Longstreet’s strategy 180 degrees and it was they who had, “force[d] the enemy to attack [them], in such good position as [they] might find.”

I will create some other Gettysburg scenarios including ones with the Union and Confederate cavalry available. While not historical, it might make for some interesting gameplay and Human-Level AI decisions.

As always, please feel free to contact me directly with comments.