Hexagons are ubiquitous in wargames now (indeed, both Philip Sabin’s War: Studying Conflict Through Simulation Games and Peter Perla’s The Art of Wargaming feature hexagons on their book covers), but this wasn’t always the case. My first wargame – the first board wargame for many of us – was Avalon Hill’s original Gettysburg (by the way, $75 seems to be the going price for a copy on eBay these days).

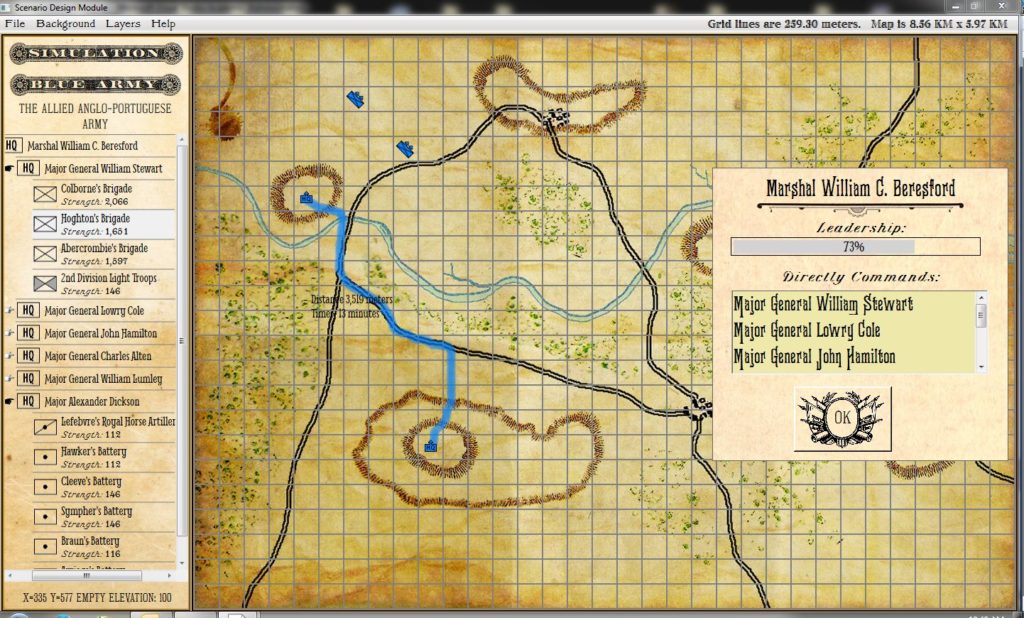

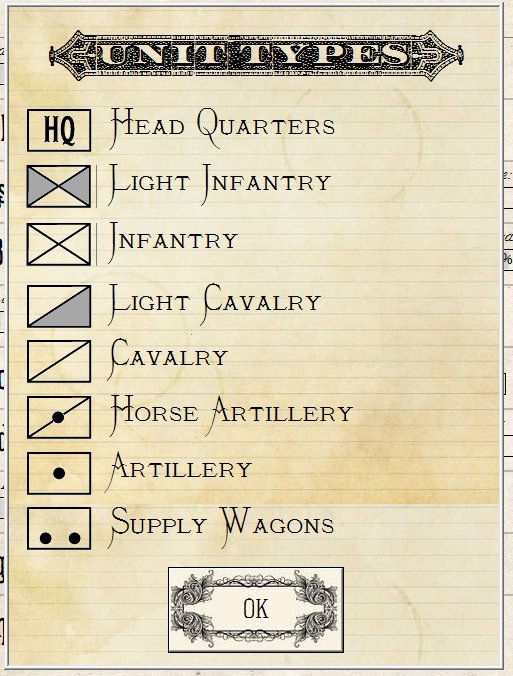

No hexagons in Avalon Hill’s original Gettysburg. Remember how the map contained the original starting positions for the Union cavalry and out posts? From author’s collection. (Click to enlarge)

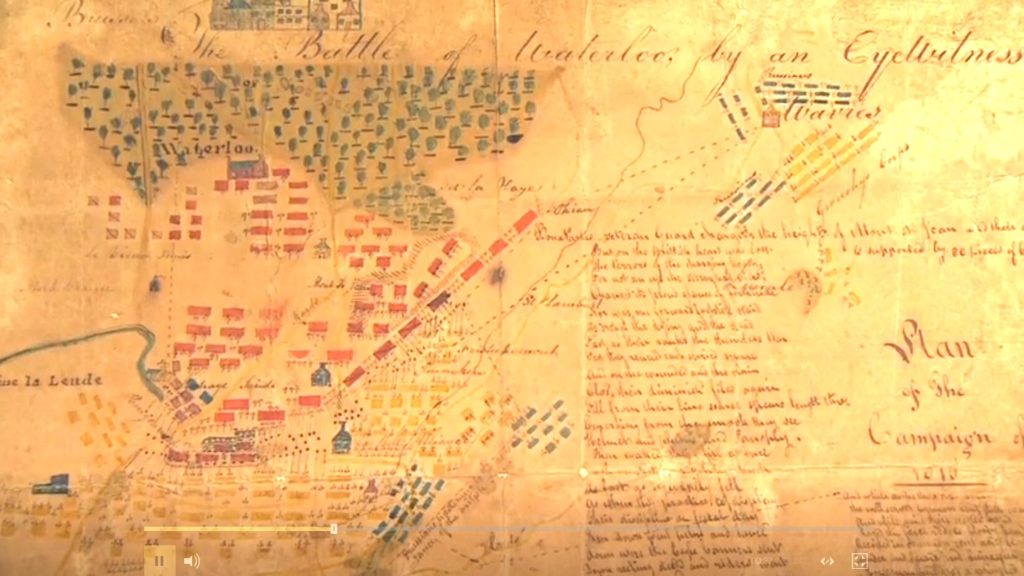

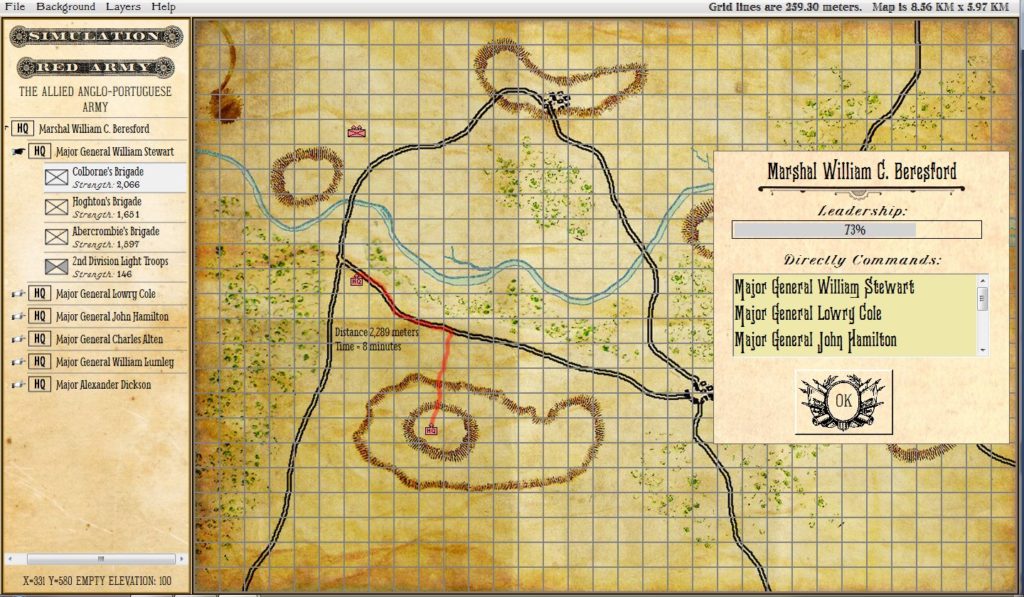

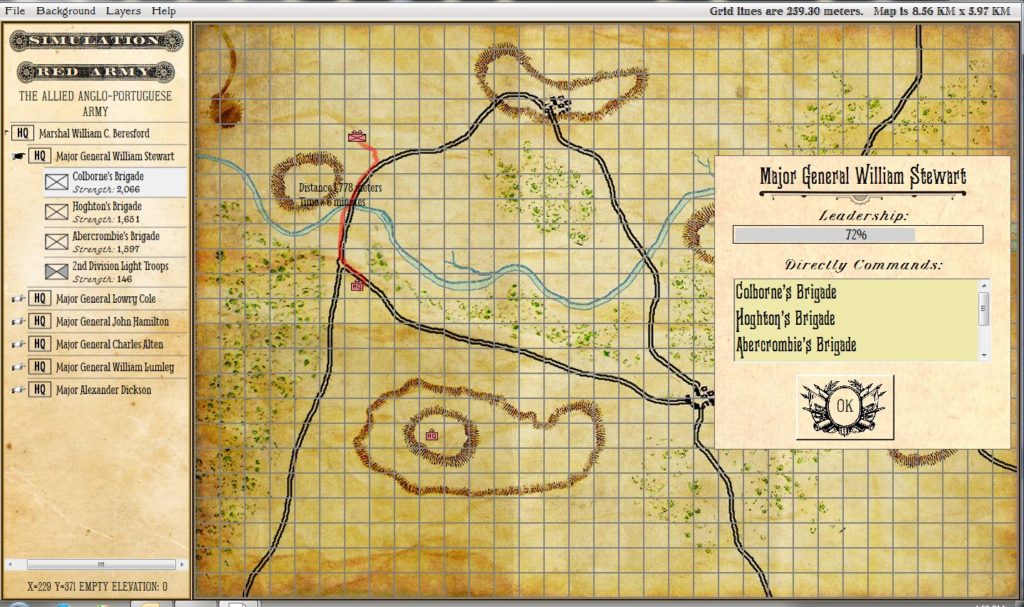

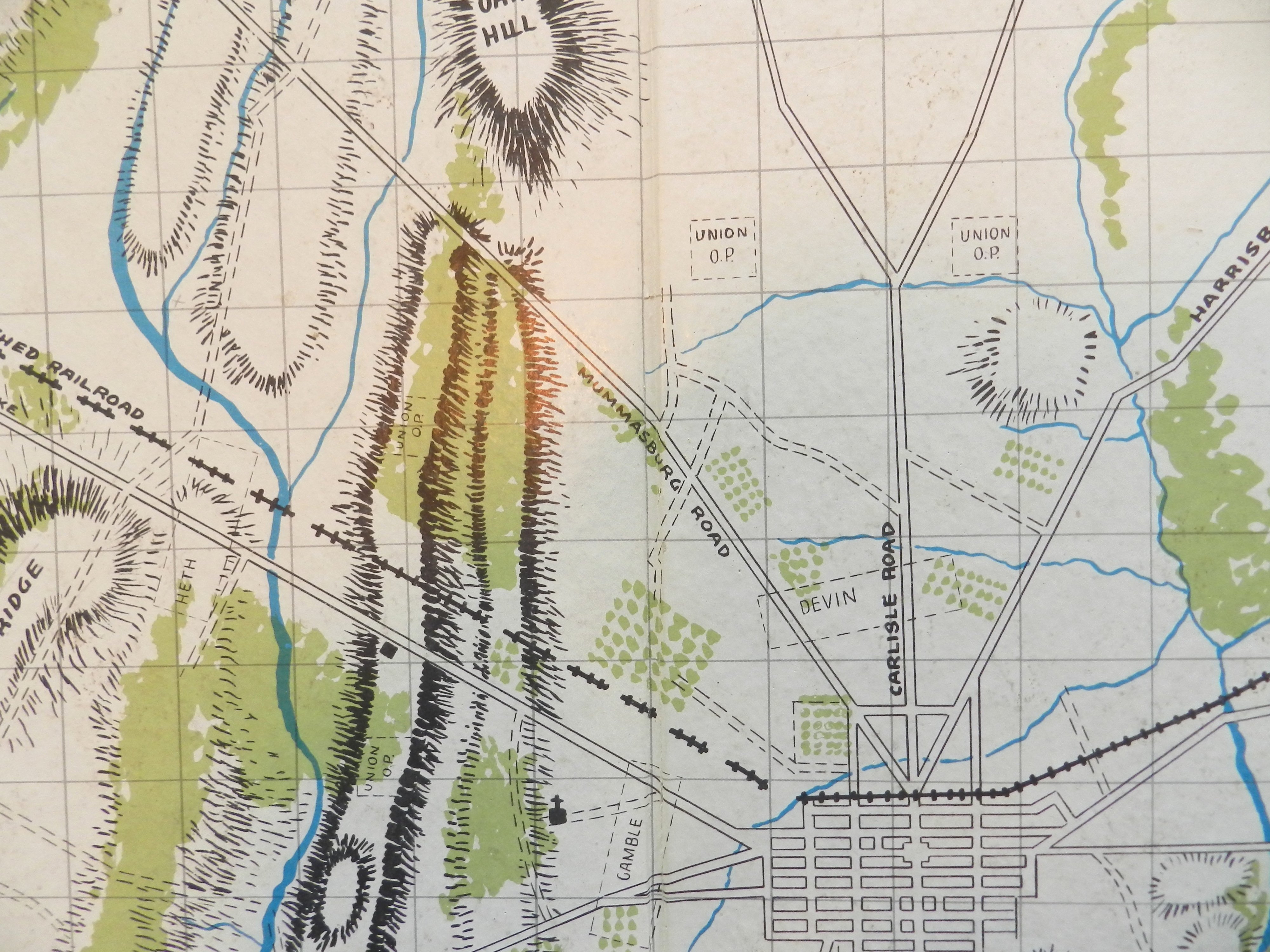

The American Kriegsspiel by Captain Livermore (circa 1882) only had a map grid for estimating distances. We also have a map grid in General Staff to facilitate estimating distances but you can turn the map grid on or off.

Plate 1 from The American Kriegsspiel by Captain Livermore. Click to enlarge. This image is from GrogHeads wonderful blog post on Nineteenth Century Military War Games. Link: http://grogheads.com/featured-posts/5321

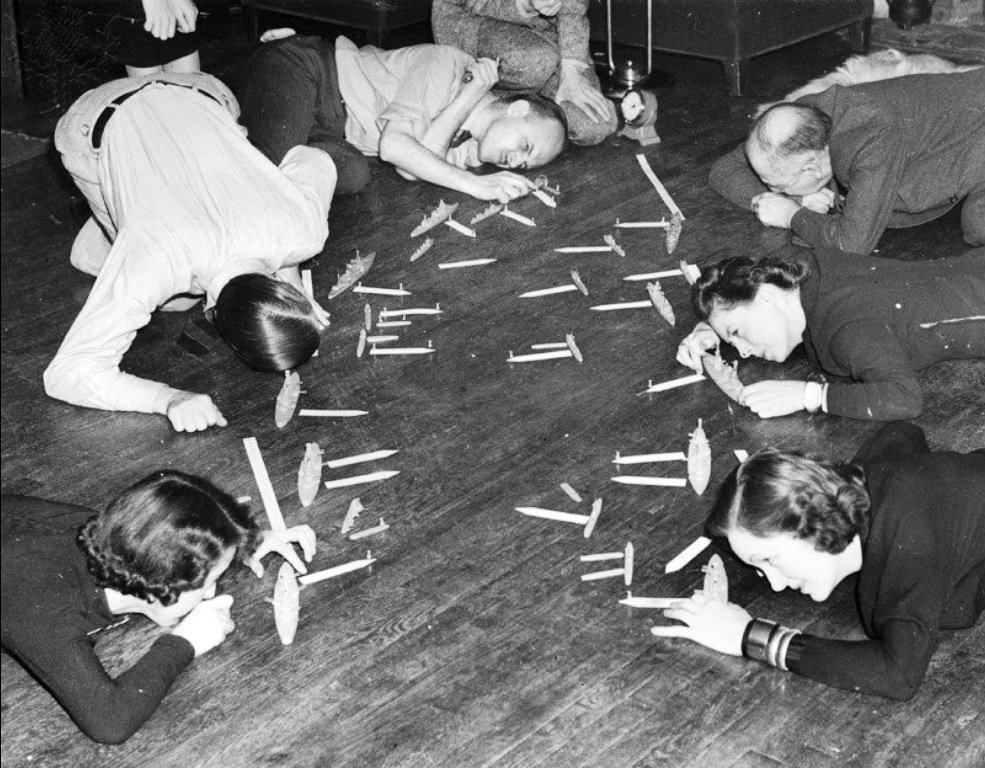

And how about this picture from the Naval War College (circa 1940s)? I just needed an excuse to post this photograph:

A Fletcher Pratt Naval War Game in progress. I never understood why they didn’t use upside down periscopes to check broadside angles rather than getting down on the floor. Click to enlarge. From this blog http://wargamingmiscellany.blogspot.com/2016/02/simulating-gunfire-in-naval-wargames.html

It is pretty common knowledge among the wargaming community that Avalon Hill’s owner, Charles Roberts, introduced hexagons to commercial wargaming in the early 1950s .

“Later, he [Roberts] saw a photograph of one of the RAND gaming facilities and noted they were using an hexagonal grid. This grid allowed movement between adjacent hexagons (or hexes, as they are more frequently called) to be equidistant, whereas movement along the diagonals in a square grid covered more distance than movement across the sides of the squares. Roberts immediately saw the usefulness of this technique and adopted to his subsequent games.”

– The Art of Wargaming, Perla, p. 116

In researching how the RAND Corporation – a major post-war defense think tank – came up with the original idea of employing hexagons to simplify movement calculations (as well as the invention of the Combat Resolution Table or CRT) I stumbled upon an amazing document: Some War Games by John Nash and R. M. Thrall (Project RAND, 10 September 1952; available as a free download here). Yes, that is THE John Nash; A Beautiful Mind John Nash; the Nobel Prize recipient John Nash. The Some War Games summary states:

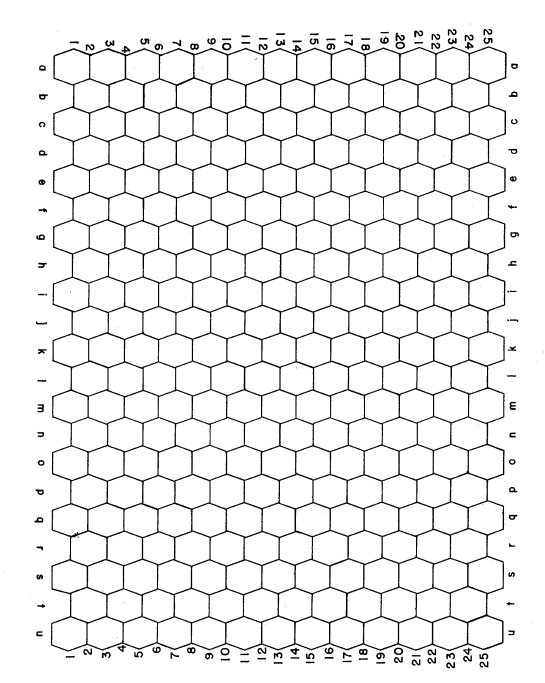

“These games are descendants of the one originally instigated by A. Mood, and are both played on his hexagonal-honey comb-pattern board. – Some War Games Nash & Thrall.

But what appears on Page 1A of Some War Games is even more exciting:

The earliest reference of using hexagons for wargames. “The board is a honeycomb pattern of hexagonal “squares,” the same that was used in Mood’s game” – From Some War Games (Project RAND, Nash & Thrall).

Sadly, I have been unable to find an actual copy or documentation for “Mood’s game,” but did discover that A. Mood was a statistician who wrote the popular text book, “Introduction to the Theory of Statistics,” and, during World War II was involved with the Applied Mathematics Panel and the Statistical Research Group. Mood was also the author of, “War Gaming as a Technique of Analysis,” September 3, 1954 which is available as a free download here. Unfortunately, I have yet to uncover any images of Mood’s original war game and the very first use of his ‘honeycomb pattern’ board.

Let’s take a quick look at the math behind hexagons:

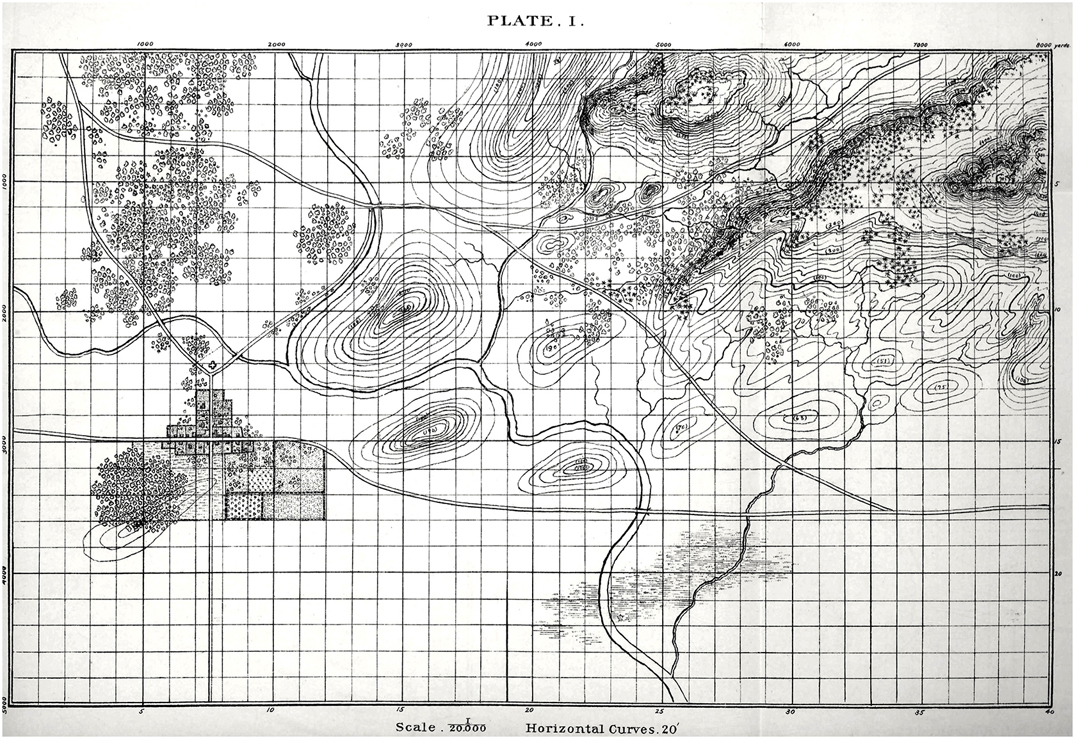

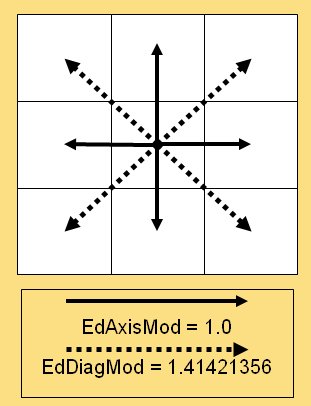

The cost of moving diagonally as opposed to horizontally or vertically on a map board (from a slide in my PhD Qualifying Exam on least weighted path algorithms).

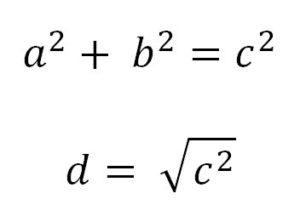

The problem of quick and easy movement calculation (as shown in the above graphic) is caused by the Pythagorean Theorem. Well, not so much caused, as a result of the theorem:

The distance to a diagonal square, d, is the square root of the square of the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) which is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. We all learned this watching the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz, right?

In other words, if everybody could just multiply by 1.41421356 in their heads we wouldn’t even need hexagons! The downside, of course, is now we’ve restricted our original eight axes of movement to six. And there’s another problem; what I call the, “drunken hexagon walk.”

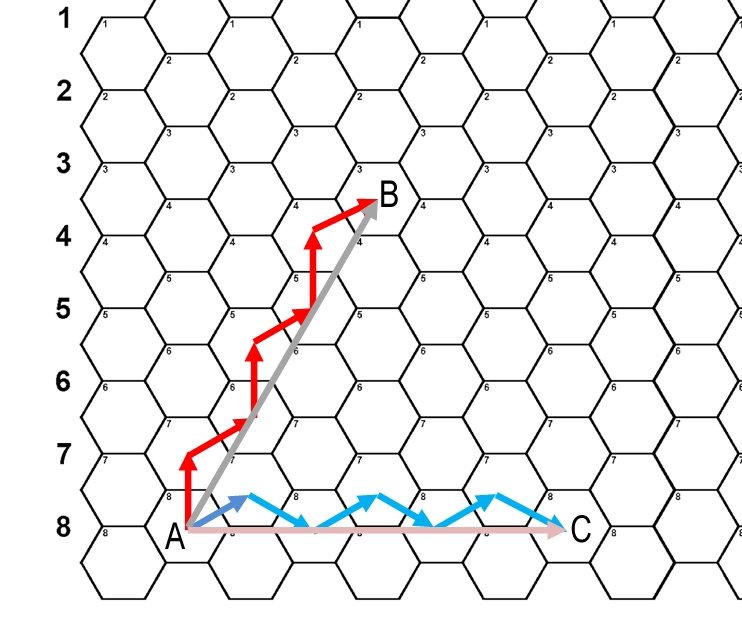

An example of “drunken hexagon walk” syndrome. All we’re trying to do is go in a straight line from Point A to Point B and from Point A to Point C.

In the above diagram we just want to travel in a straight line from Point A to Point B. It’s a thirty degree angle. What could be simpler? How about traveling from Point A to Point C? It’s a straight 90 degree angle. It’s one of the cardinal degrees! What could be simpler than that? Instead our units are twisting and turning first left, then right, then left like a drunk stumbling from one light post to another light post across the street. In theory the units are actually traversing considerably more terrain than they would if they could simply travel in a straight line. This is the downfall of the hex: sometimes it simplifies movement; but just as often it creates absurd movement paths that no actual military unit would ever take.

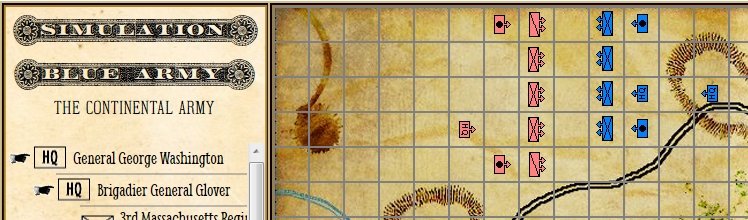

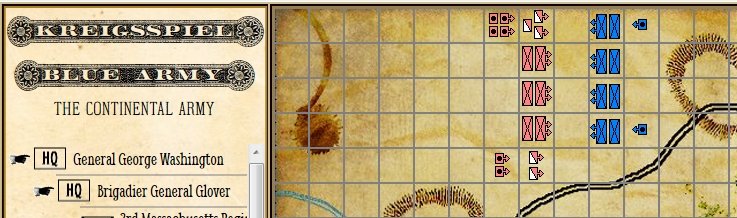

So, what’s the solution? Clearly, there is no reason why a computer wargame should employ hexes. Computers are very good at multiplying by 1.41421356 or any other number for that matter. Below is a screen shot of General Staff:

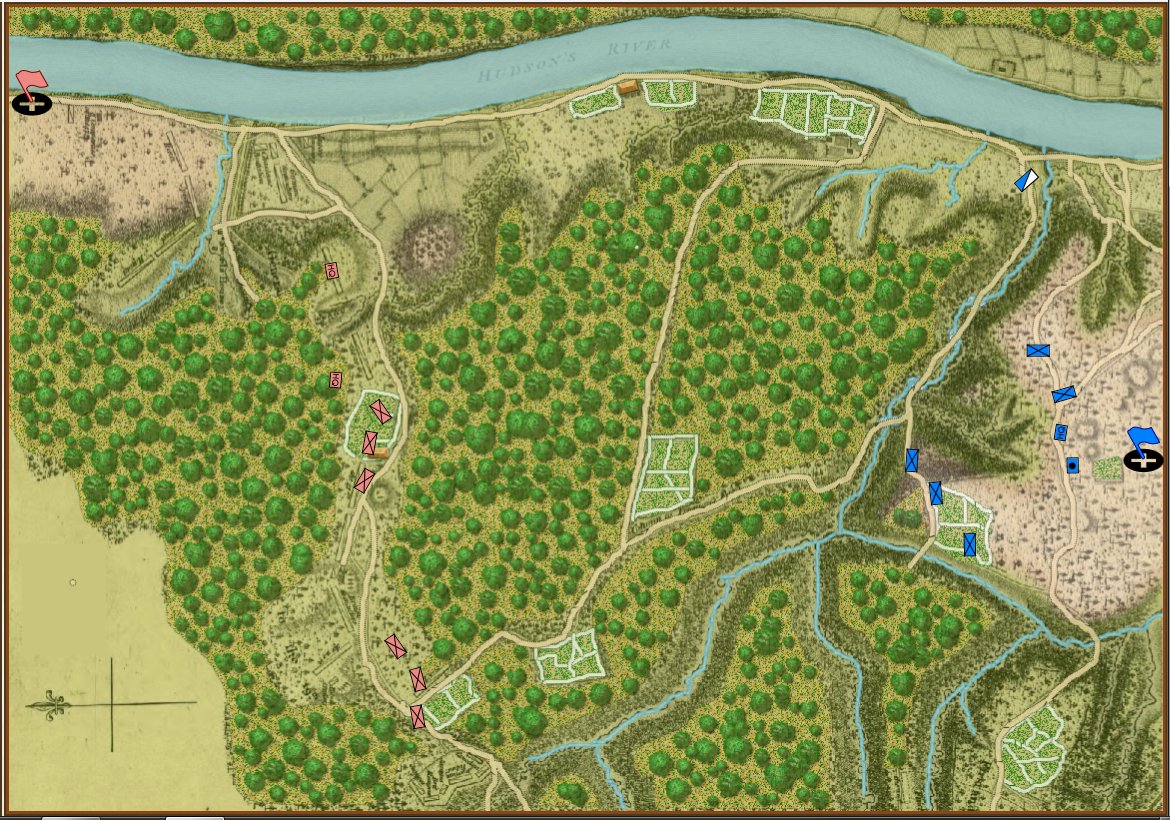

Screen shot of General Staff (2nd Saratoga) based on the map of Lt. Wilkinson, “showing the positions of His Excellency General Burgoyne’s Army at Saratoga published in London 1780) . Click to enlarge.

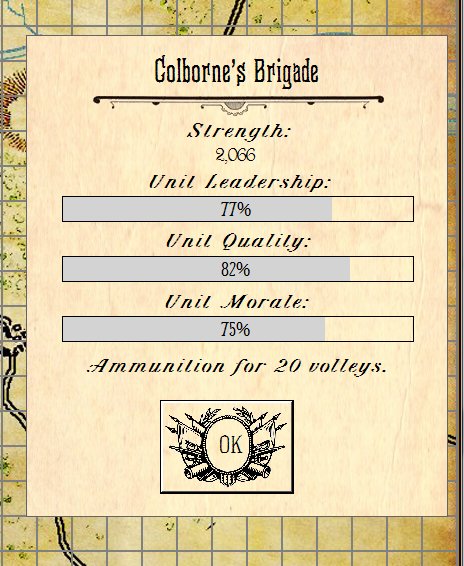

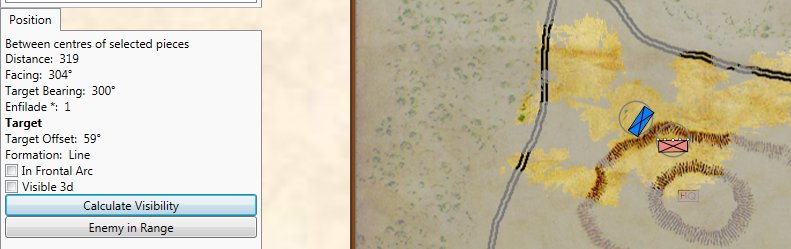

What’s missing from the General Staff screen shot, above? Well, hexes, obviously. Units move wherever you tell them to in straight lines or following roads precisely if so ordered. And units can obviously face in 360 degrees. Consider this screen shot from the General Staff Sandbox where we’re testing our combat calculations:

Screen shot from the General Staff Sandbox. Notes: 3D unit visibility is turned on, displayed values: unit facing, distance, target bearing, enfilade values, target offset. Click to enlarge.

For board wargames hexagons seem to be a necessary evil unless you want to break out the rulers (that never stopped us with the original Gettysburg or Jutland). But, when it comes to computer wargames, I just don’t see the upside for hexagons but I do see a lot of downside. And that’s why General Staff doesn’t use hexes.