We’ve just added a video showing the MATE 2.0 tactical artificial intelligence playing Blue (Union Army of the Potomac) against Red (Confederate Army of Northern Virginia) at Antietam. This video also includes an announcement that we’ll be working on getting the Army Editor, Map Editor and Scenario Editor installation packages and keys ready on Steam.

Category Archives: Fog of War

Video Walk-through of the Army, Map & Scenario Editors

I‘ve just uploaded a video of a walk-through of the General Staff: Black Powder Army Editor, Map Editor and Scenario Editor. These applications are completed. We will be using Steam for distribution. While we are registered with Steam, and they have given us ‘our space’, we still have to build it out and make arrangements for download keys for early backers. We (why do I keep using ‘we’, it’s just me here) truly appreciate your patience.

I will be posting a gameplay video of General Staff: Black Powder next. As always, please feel free to contact me directly.

The Friction of War

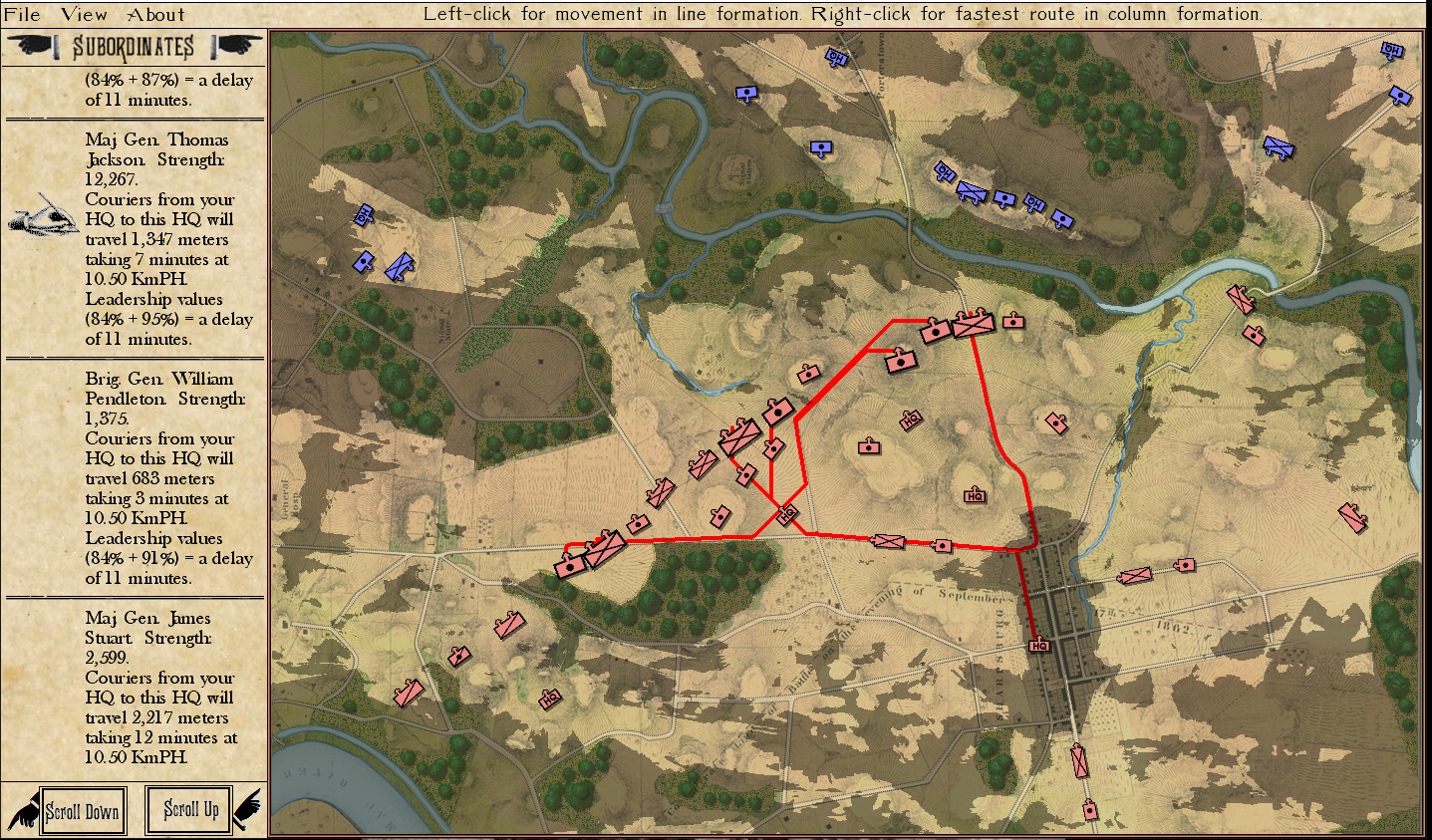

The delay in the transmittal of orders from headquarters and staff is one example of the Friction of War. Note the calculated time for couriers to arrive displayed in the Subordinate Orders list on the left of the screen. The red lines are the routes that couriers from General HQ to Corps HQ to individual units will take. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

Carl von Clausewitz, in has seminal work, On War, (Book 1, Chapter 7) originated the phrase, “Friction of War”:

“Friction is the only conception which, in a general way, corresponds to that which distinguishes real war from war on paper. The military machine, the army and all belonging to it, is in fact simple; and appears, on this account, easy to manage. But let us reflect that no part of it is in one piece, that it is composed entirely of individuals, each of which keeps up its own friction in all directions.”

I knew that if General Staff: Black Powder were to be an accurate simulation, and not just ‘war on paper’, that the friction of war would have to be calculated into the command / orders chain. One part of this – the distance the couriers will travel from one headquarters to the next to deliver their orders and the time it takes to travel this distance – can be calculated with reasonable certainty (I’m using the rate of 10.5 kilometers per hour for a horseman, I’m not an expert but this seemed reasonable, and it’s easy to change if somebody has a more accurate value).

Another example of friction of war is factored into the delaying of the arrival of orders is Leadership Value:

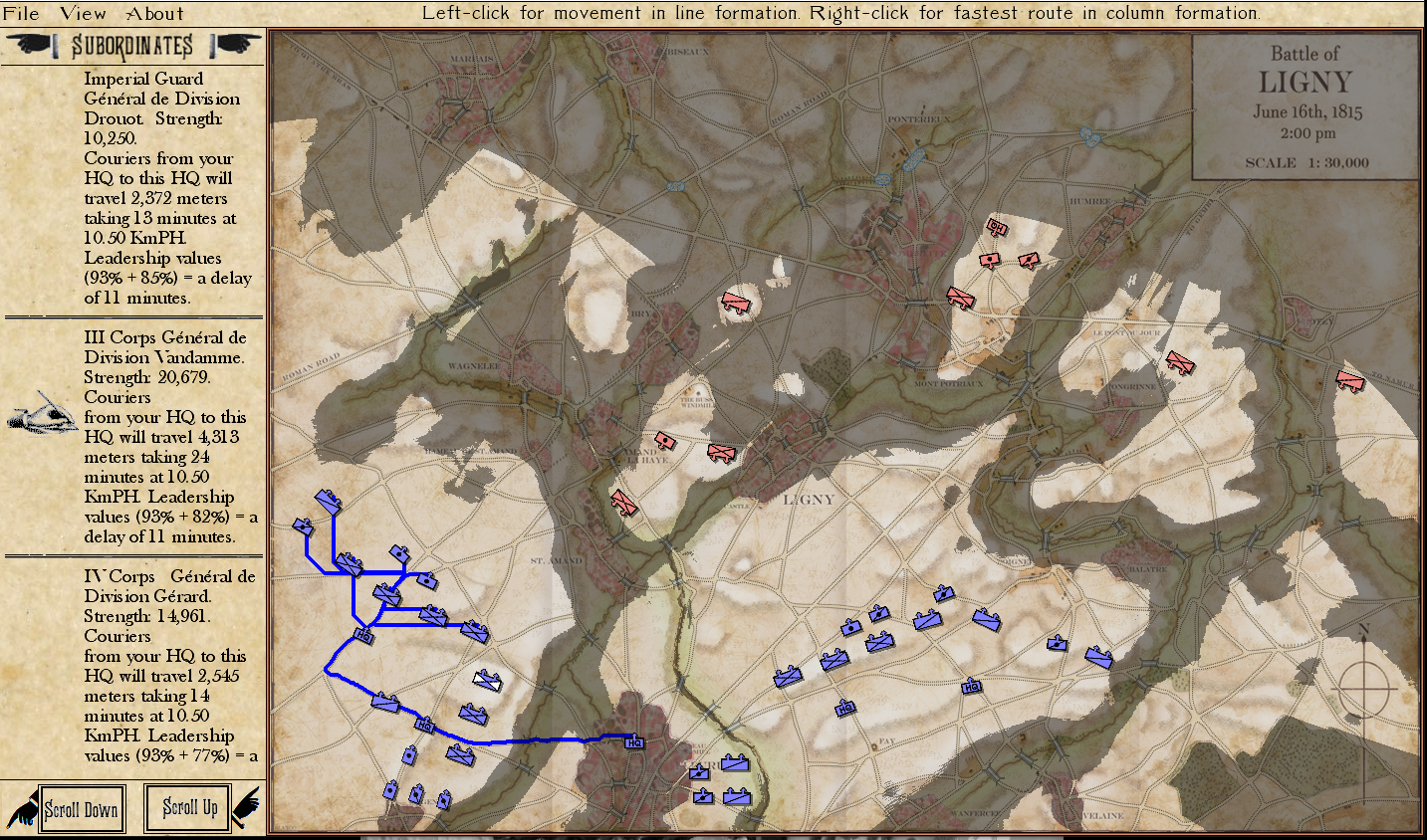

In this example, the Imperial couriers will travel over 4.3 kilometers, taking 24 minutes, to deliver their orders. Also, note the cost of the combined Leadership Values. Because Napoleon and Vandamme have very high Leadership Values little additional delay is added. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

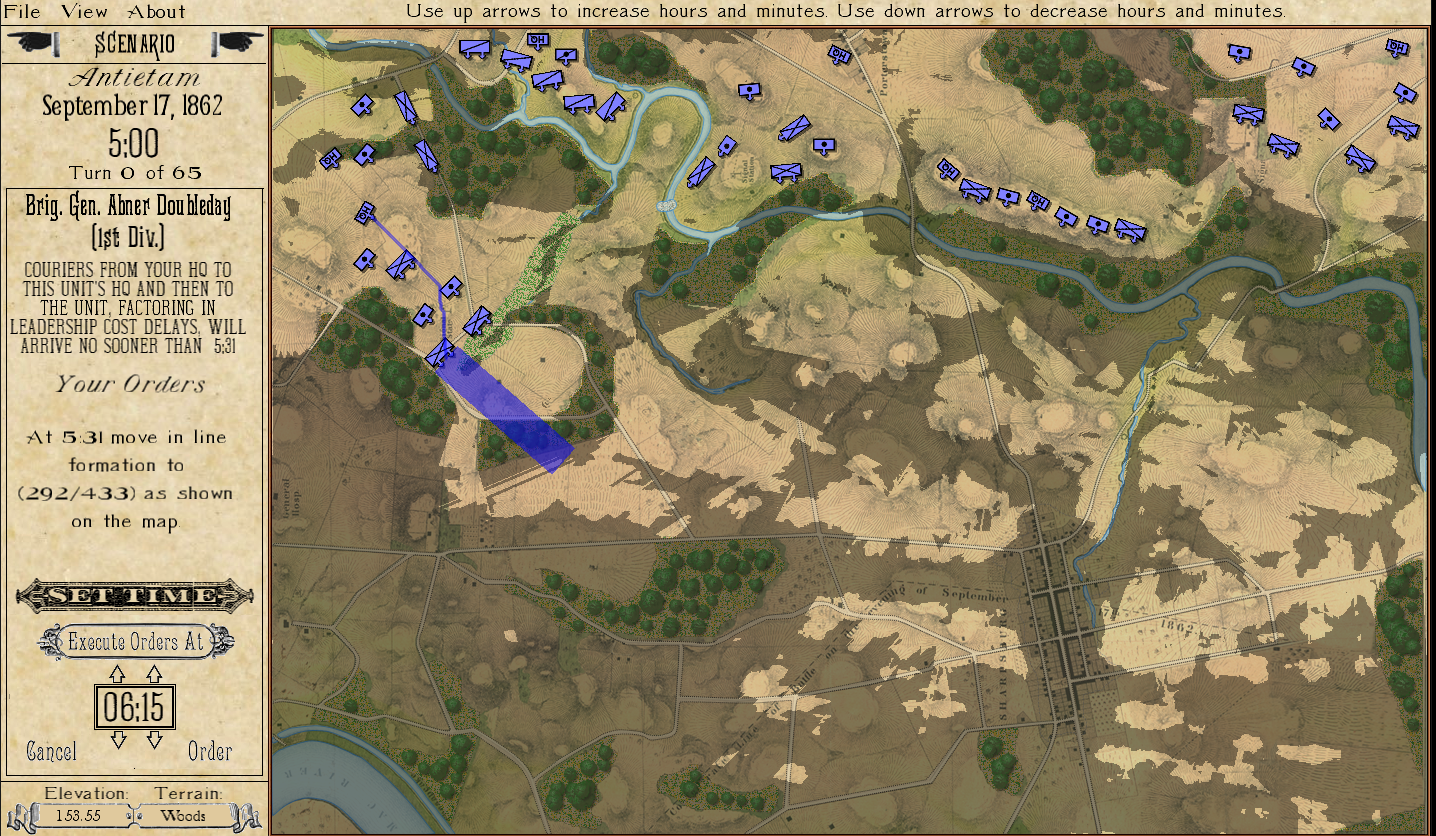

You can specify at what time the order is to be executed (in this case 6:15), however you can not set a time earlier than when the couriers would arrive. This allows for coordination of attacks across units. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

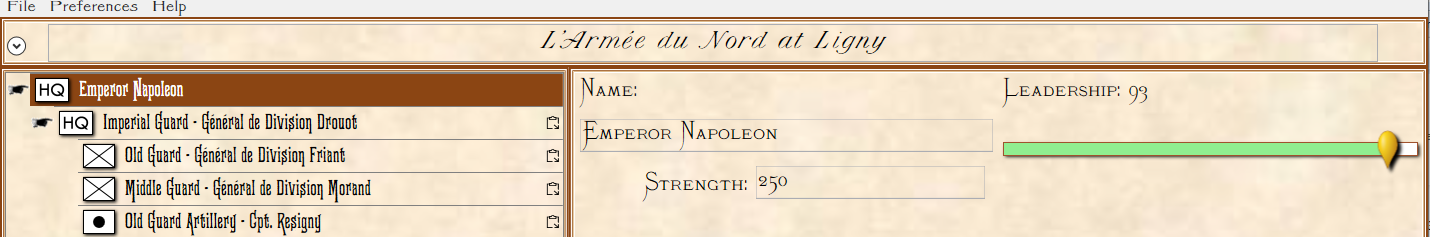

The other value – and it is arbitrarily set – is the cost of ineptitude, incompetence, lack of motivation, and sloppy staff work. In the above scenario (Ligny) Napoleon’s Leadership is set at 93%:

The slider adjusts Napoleon’s Leadership Value which effects the delay in issuing orders. General Staff: Black Powder Army Editor screen shot. Click to enlarge.

I understand that Napoleon may have been feeling a bit under the weather during the Hundred Days Campaign. You can set his Leadership Value to anything you want in the Army Editor (above).

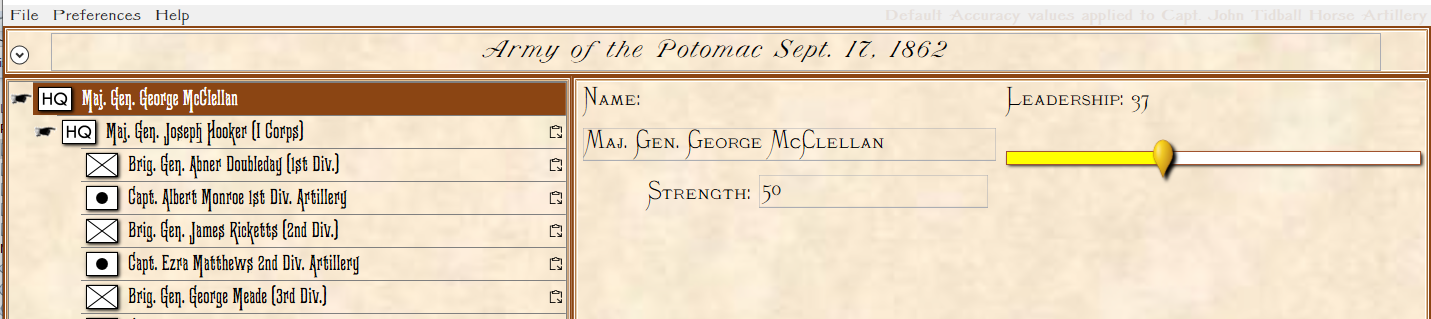

Major General George B. McClellan’s Leadership Value can be changed in the Army Editor. Click to enlarge.

Did I set McClellan’s Leadership Value too low? He was amazingly incompetent. Note below:

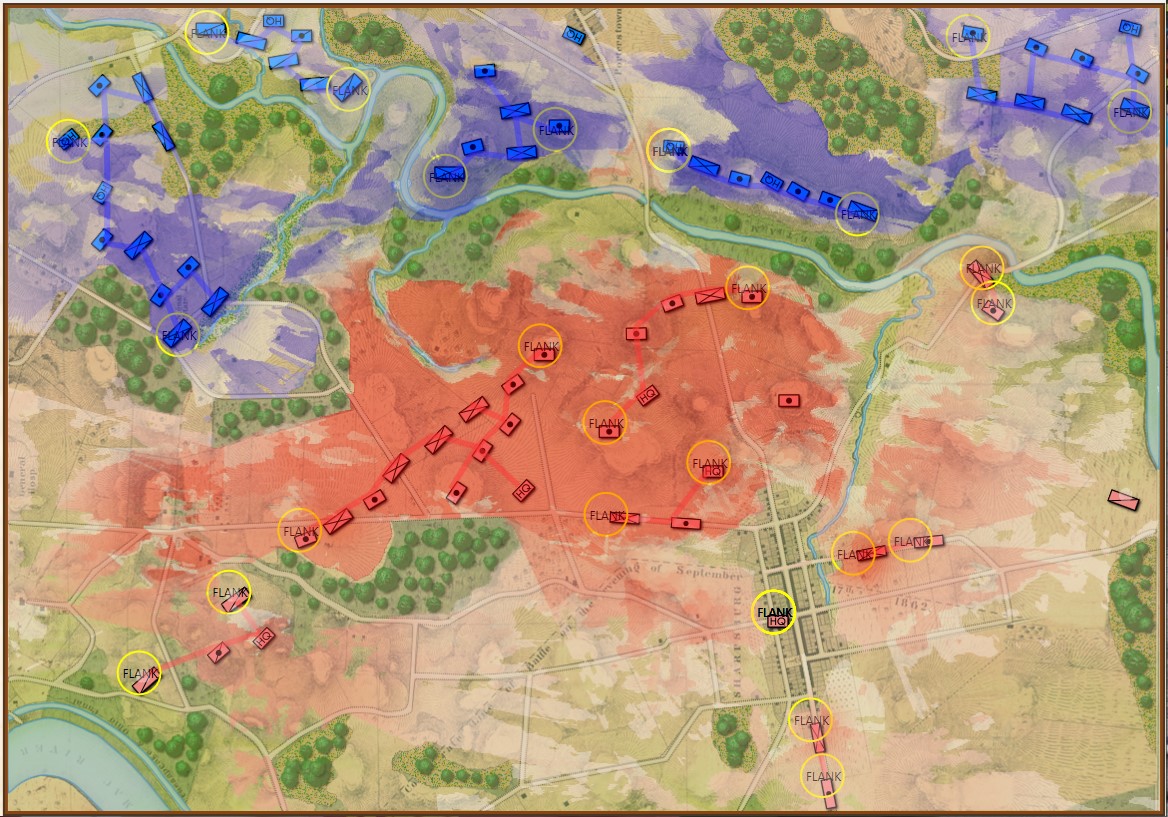

The combination of McClellan’s and Burnside’s extremely low Leadership Values adds an additional 29 minutes to the transmittal of orders. The blue lines trace the route that couriers would travel from McClellan’s headquarters to Burnside’s headquarters and then to each division and battery. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

The combination of McClellan’s and Ambrose Burnside’s Leadership Values results in almost a half hour delay in transmittal of the orders (remember after receipt of the orders, Burnside has to send couriers to his divisional and battery commanders, too and their Leadership Values effects the delay before their unit executes the order). After factoring the time it would take for a horseman to travel the distance between McClellan’s headquarters to Burnside’s headquarters (14 minutes) the earliest that a unit could be expected to respond to the original order from General Headquarters would be forty-one minutes later (and, in reality, a bit after that because of that unit’s Leadership Value).

The path of the couriers from McClellan’s headquarters, to Burnside’s Headquarters and then out to the divisions and batteries. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

I have spent some time at Antietam and studied it at length and this delay of about three-quarters of an hour between the time McClellan wanted to issue an order and the men of Burnside’s IX Corps moved out seems if anything, too optimistic of a timetable. In fact, as I write this, I think I need to increase the penalty for poor Leadership Value. McClellan and Burnside couldn’t possibly have got units moving in less than an hour.

As I have begun playtesting General Staff: Black Powder I found the delay between issuing orders and wanting to see something move now was a bit disconcerting. It shouldn’t have been. I’ve read enough military history to know that battlefield orders were often transmitted the night before and moving units around during the battle could be a risky proposition. Some armies, however, were less afflicted with these problems than others, and that I would attribute to ‘leadership value’ which also encompasses the army’s general staff.

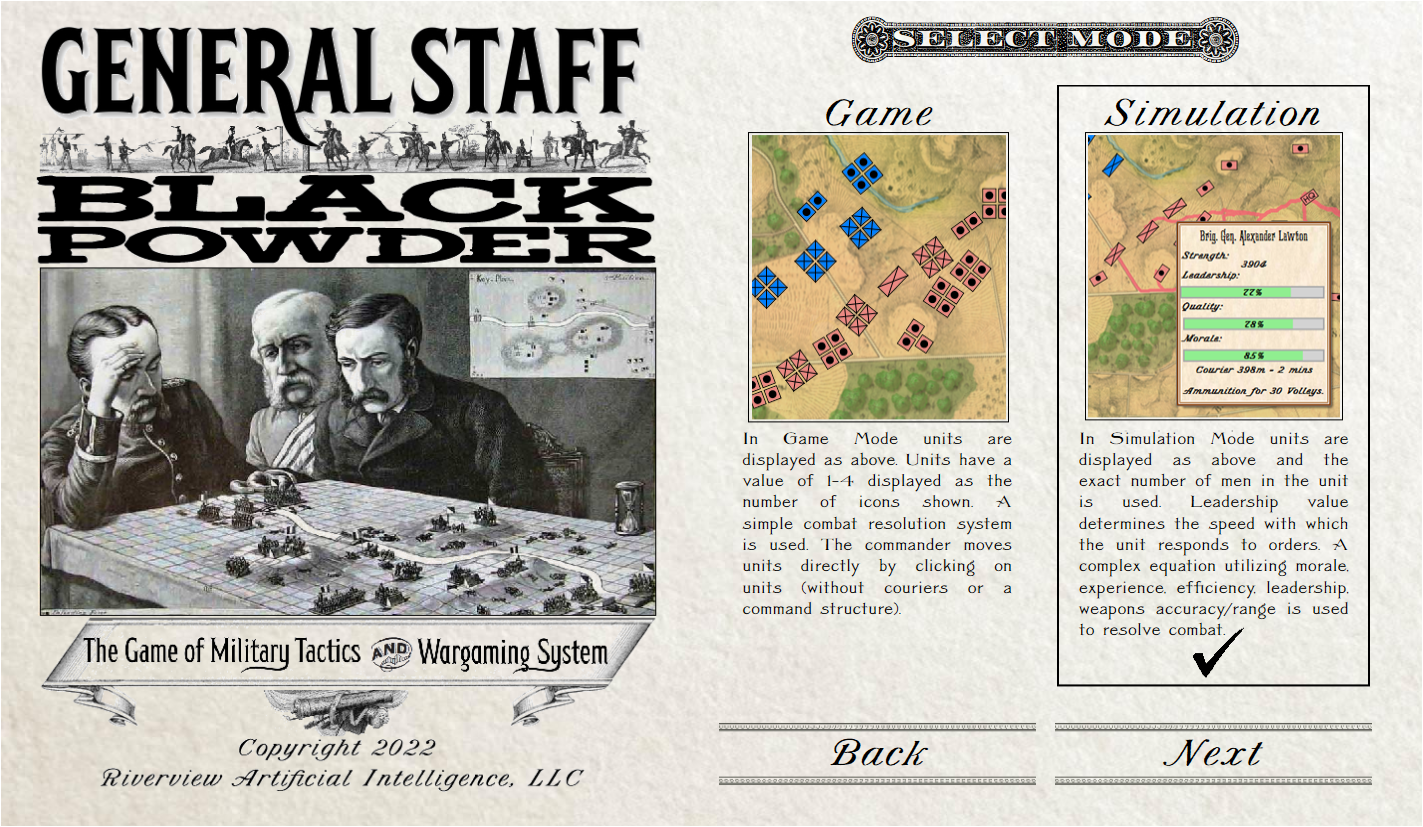

If you don’t want to use General Staff: Black Powder as a simulation that inserts a calculated delay between orders and execution, and would rather just move units instantly, there is ‘Game Mode’:

The Select Mode screen in General Staff: Black Powder. The user chooses between ‘game’ and ‘simulation’ with differences in rules and unit icons. Click to enlarge.

Game Mode has the same maps but uses simpler icons and rules. I originally envisioned Game Mode as a way of introducing wargaming to a new generation (I wanted to write it for the XBox). Anyway, it’s included with General Staff: Black Powder.

Lastly, I know everybody is waiting for news about when can I get my hands on the game?!!?!! My friend, Damien, wasn’t able to work on finishing it using Unity so I’m finishing it up using MonoGame. As you can see I’m pretty far along and I think I will be playing the first ‘actual game’ (that is a simulation from start to finish) within the next couple of weeks; maybe sooner. After that, probably at least another month of fixing bugs, but then I’m hoping to set up a Beta download for all the early backers via Steam. We have a space on Steam but I haven’t even begun to build it out. Obviously, I’m just one guy, I’m working as fast as I can, but I think this is all good news. Also, I’m working on a video to show everything off.

As always, if you have any questions or comments, please feel free to contact me directly.

Layers: Why a Military Simulation Is Like a Parfait

Detailed military simulations and wargames are made up of layers1)Here is the obligatory link to Shrek and the layers, onions and parfait bit. by necessity. Layers keep simulation designers and users from being overwhelmed by oceans of data. In General Staff every scenario (battle) is made up of these layers (some are optional):

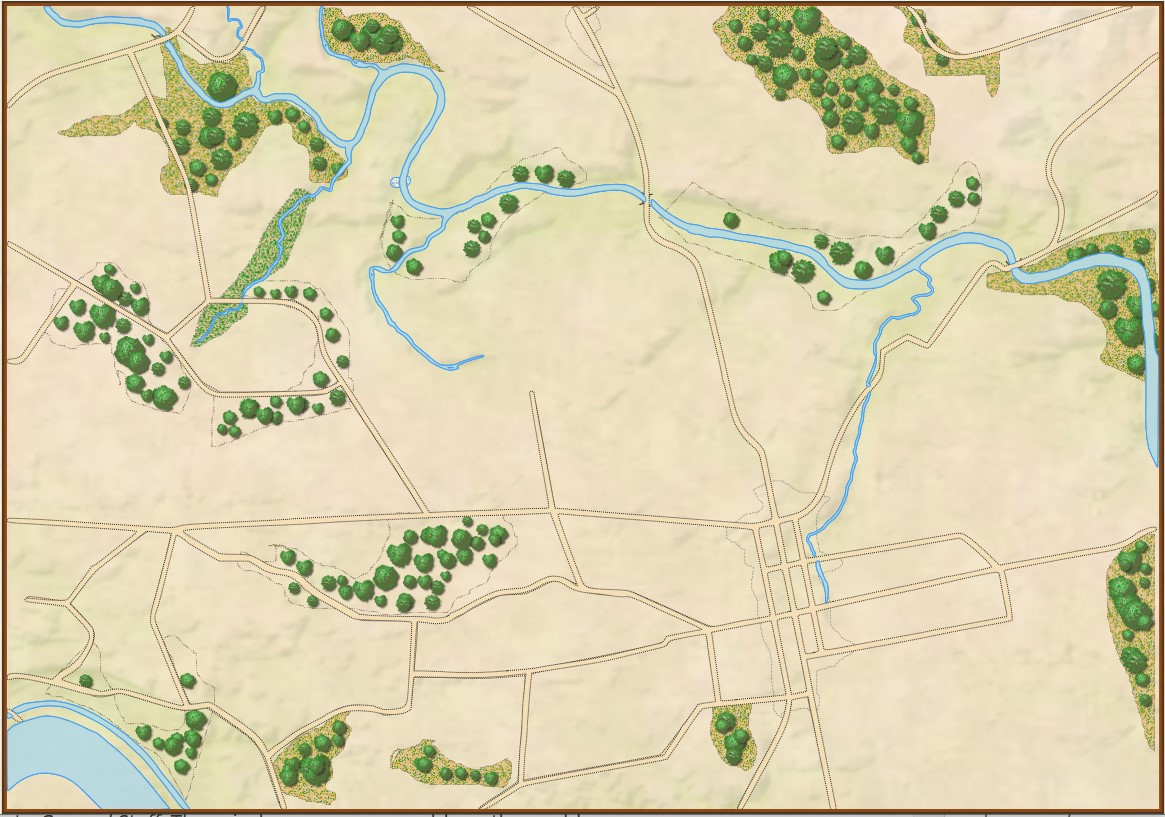

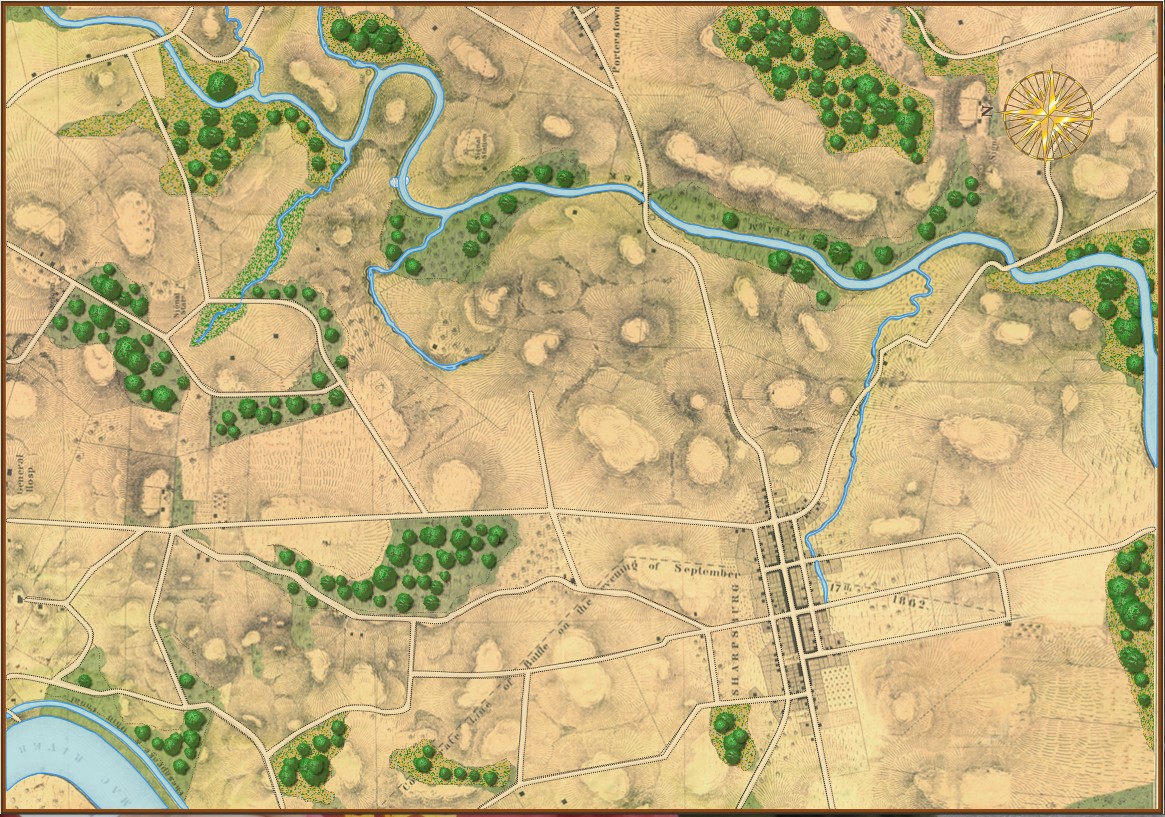

The Background Image. Ironically named because even though it’s underneath all the other layers it’s makes up most of what the user sees of the battlefield. However, the background image contains no data that is actually used by the computer; it is completely ‘eye candy’ for the user. That said, us humans get most of our data from looking at this map (we can make sense of the hills, roads, forests, rivers, etc.). But that’s not how computer vision works (see below).

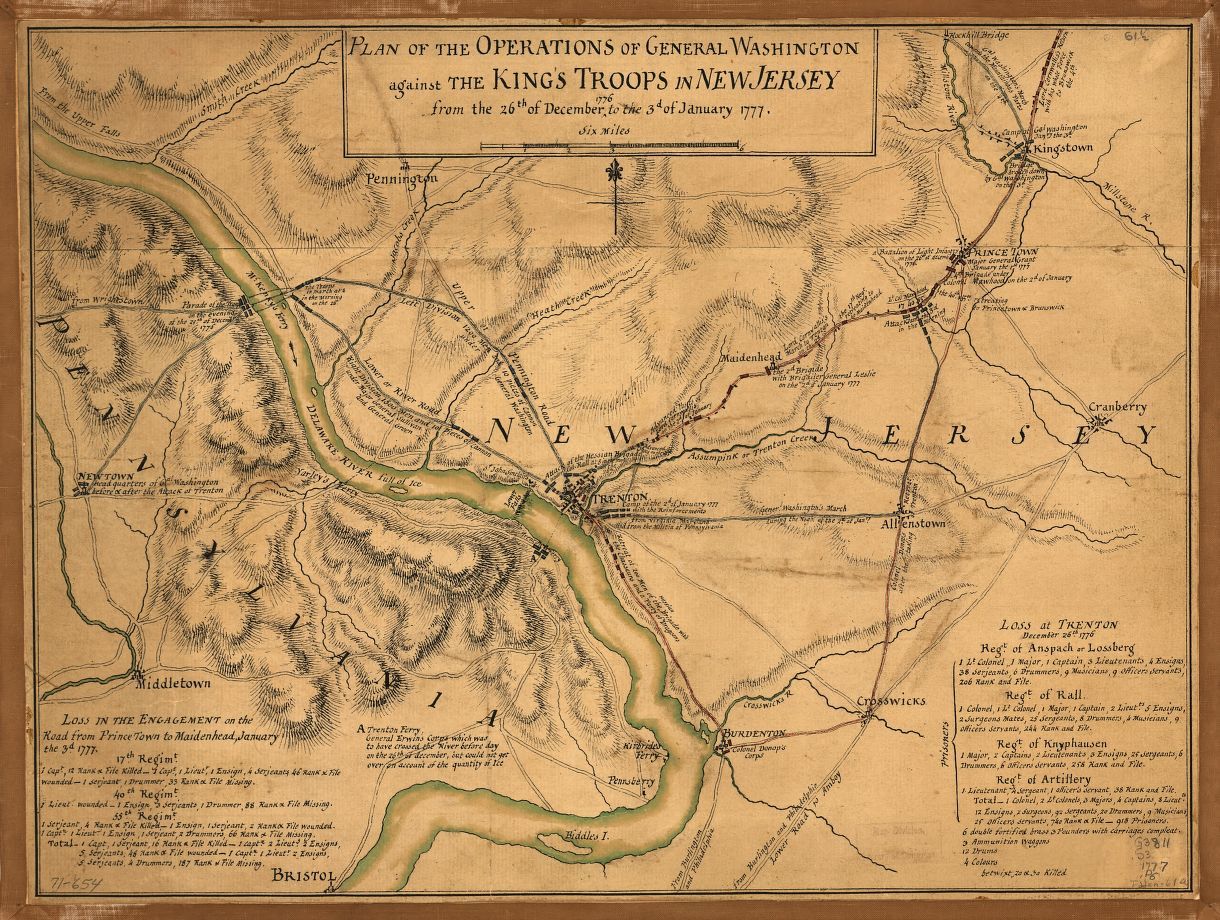

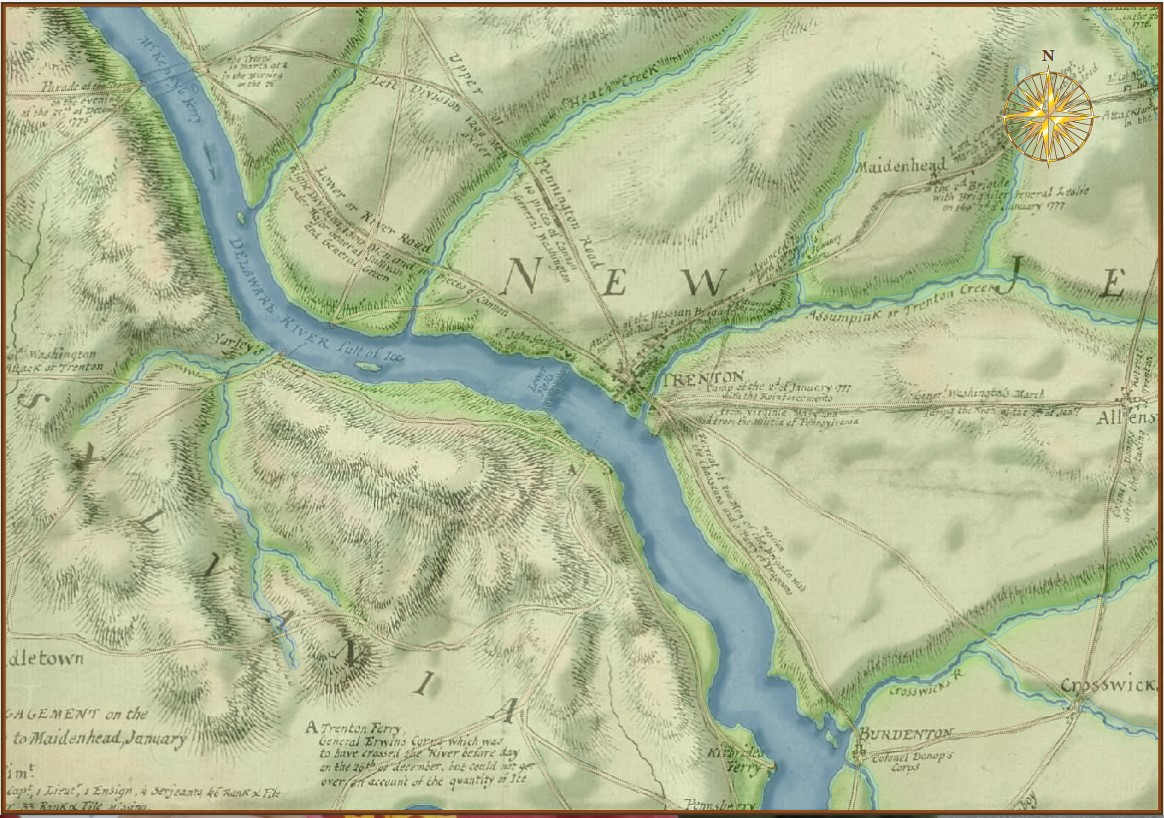

This map came from the Library of Congress (here). The Library of Congress is a great place to get royalty-free battlefield maps from American history. Personally, it’s exactly these old maps that inspired me to create General Staff. There is, however, one problem: these old maps are just not ‘GPS accurate’. That is to say, even though the General Staff Map Editor allows the user to directly import Google Maps elevation data, it won’t align properly with maps made over a hundred years ago without GPS data. That means the scenario designer will have to enter the elevation data by hand and not import it from satellite data.

The Terrain Layer. This layer is a visual display of what the computer ‘sees’ of the terrain: forests, water, fences, hedges, walls, swamp, mud, field, city, road, river, fortification, buildings (seven kinds), fords, and bridges.

The Terrain Drawing tab (right). This is one of the tabs in the General Staff Map Editor (click here to go to the online Wiki for more detailed information). Click on the desired terrain type and then draw with either the mouse or a digitizing tablet and pen. I have absolutely no drawing abilities, but I’ve watched actual artists create a map using a digitizing tablet and pen in about 30 minutes. If you’re drawing a river, the harder you press with the digital pen the wider the river gets.

There are three ways you can input water and roads in the Map Editor: mouse, digitizing tablet and XAML code. For me, because I have very limited drawing abilities, I find using XAML code the easiest (below):

The Road Net Layer (optional). This image (below) was created in a paint program (PhotoShop, though any paint program that you’re comfortable with will work just fine). It was then imported into Inkscape (free download here) and exported as XAML.

The Water Layer (optional). Like the Road Net image (above) this was created in a paint program (PhotoShop). It was then imported into Inkscape (free download here) and exported as XAML.

The Elevation Layer. There are four ways to input elevation in the General Staff Map Editor: you can draw with the mouse, use a digitizing tablet and pen, input elevation data directly using Google Earth and directly importing a BMP image.

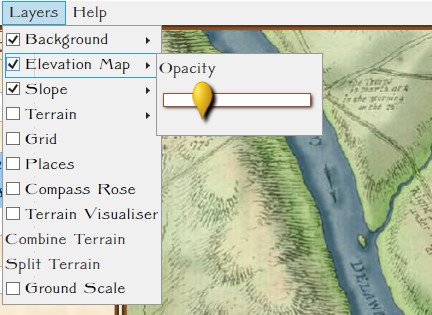

The Slope Layer. This layer shows the extrapolation of slopes from the elevation layer (above). Combined with the Background, and Elevation layer it can produce a dramatic 3D effect. See Trenton, below.

Blending Multiple Layers. This is a blend of the Background, Elevation, Terrain and Slope layers. The user can set the blend values (see screen shot from the Map Editor, right).

Blending Multiple Layers. This is a blend of the Background, Elevation, Terrain and Slope layers. The user can set the blend values (see screen shot from the Map Editor, right).

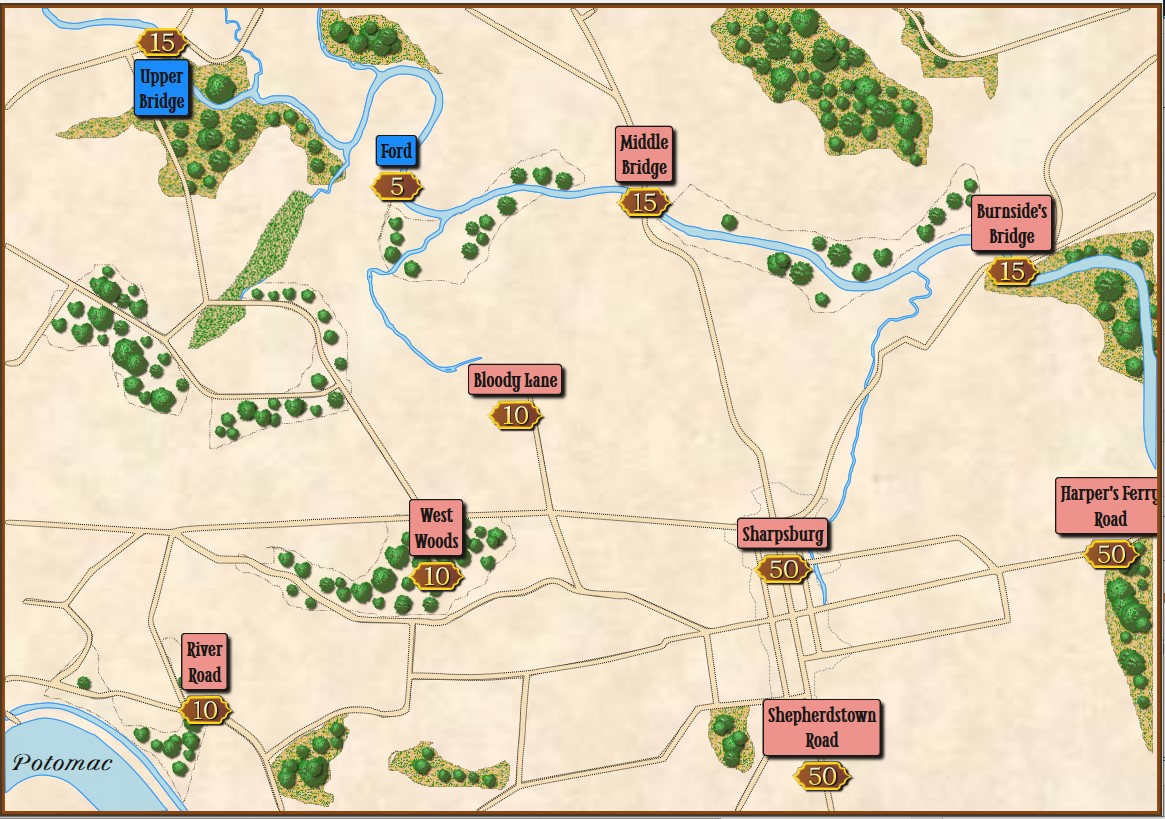

The Places and Victory Points Layer. This layer allows you to set certain locations as Victory Points or Placenames. A Placename is a descriptive text placed on the map that has no importance to the simulation; e.g. labeling the Potomac River (below).

The Units Layer. This is a visual representation of the current simulation state showing unit locations. This information may be filtered by Fog of War (FoW) and what units can observe other units (both friend and foe) using 3D LOS (see below):

The Units layer for Antietam. Note: reinforcements are displayed on this layer even though they won’t enter the scenario until later. This screen shot was taken from the Scenario Editor. Click to enlarge.

The Fog of War Layer. This layer is a visual representation of what can be observed from any point on the battlefield; in this case, the 3D LOS view from the Pry House (McClellan’s Headquarters at Antietam).

The AI Layer. This layer is a visual representation of the output of a number of AI algorithms including Range of Influence (ROI), battle groups, and flank units. This is how the AI ‘sees’ the battlefield.

Trenton. I recently began working on a Trenton scenario. One of the best places to begin a search for a contemporary map of an American battle is the US Library of Congress. That is where I found the extraordinary campaign map for Trenton published in 1777.

From the above original map, Ed Kuhrt created an elevation or height map (see above) in PhotoShop. From that Elevation Layer we extrapolated the slopes and displayed them using an algorithm created by Andy O’Neill. When blended together the result is striking:

Screen shot of the Trenton map in the General Staff Map Editor. Note how the blending of the slope layer with the elevation and original background create a 3D effect. Click to enlarge.

References

| ↑1 | Here is the obligatory link to Shrek and the layers, onions and parfait bit. |

|---|

A Game of Birds & Wolves

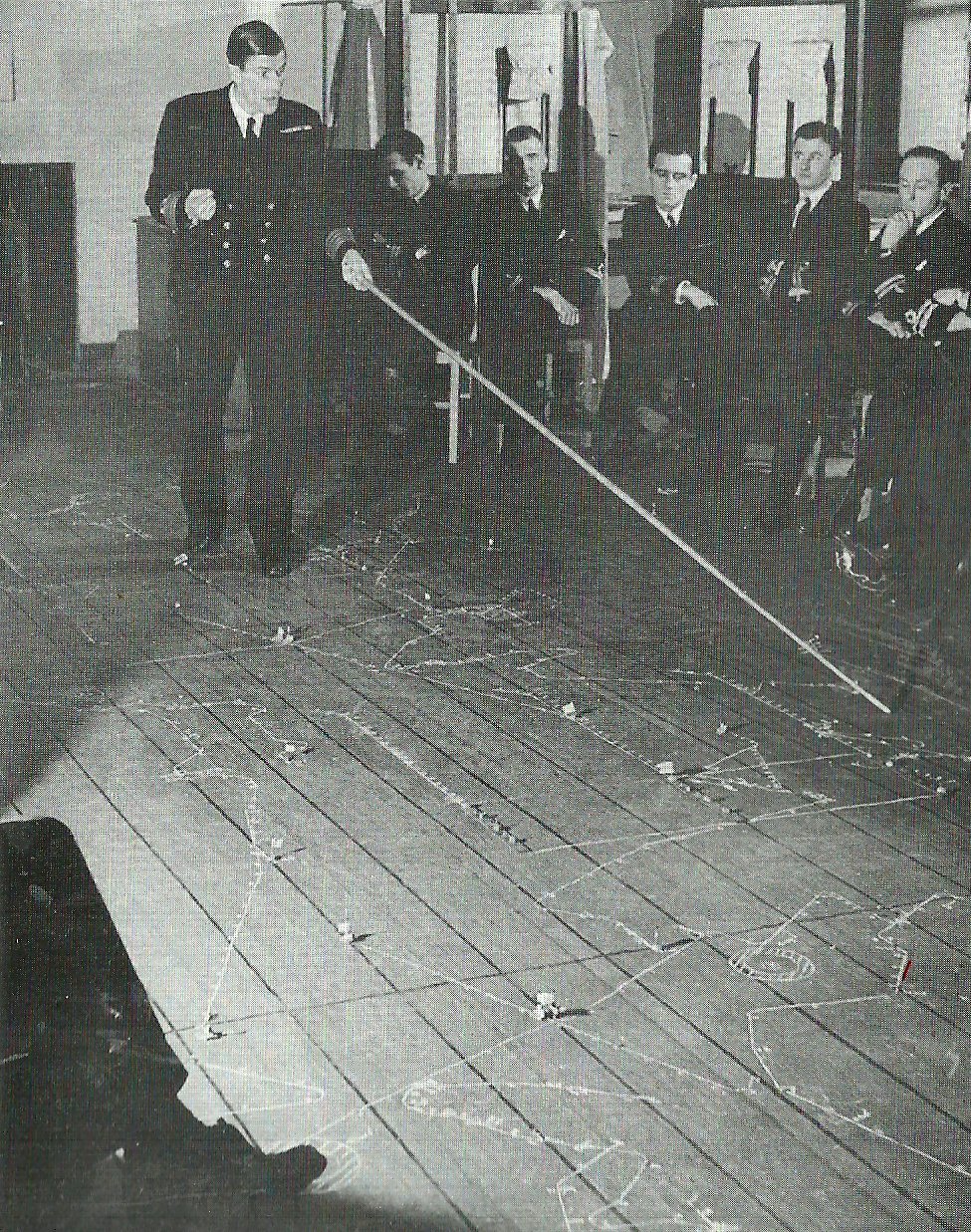

Commander Roberts going over the lessons learned from “The Game.” Photo from, “A Game of Birds and Wolves,” by Simon Parkin.

Simon Parkin’s A Game of Birds and Wolves: The Ingenious Young Women Whose Secret Board Game Helped Win World War II, tells the fascinating story of a wargame created during the height of the U-Boat Atlantic campaign to be used as a testbed for discovering new anti-submarine tactics. In early 1941, when German wolf packs were destroying Allied shipping at a devastating rate, British Naval Commander Gilbert Roberts was taken out of retirement and personally ordered by Winston Churchill to, “Find out what is happening and sink the U-boats.”

Roberts was given the top floor of the Western Approaches HQ in Liverpool and a small group of WRENs (Women’s Royal Naval Service) as assistants to invent tactics that would counter the enemy wolf packs. His project would be called the Western Approaches Tactical Unit (WATU). (The Western Approaches HQ in Liverpool is now a museum and I can’t wait to visit it when this pandemic is over and General Staff is finished.)

The WATU project – known simply as, “The Game,” – is not the first example of a wargame used as a testbed to discover and improve combat maneuvers. Indeed, Scotsman John Clerk, wrote, An Essay on Naval Tactics: Systematical and Historical in 1779 after using, “…a small number of models of ships which, when disposed in proper arrangement, gave most correct representations of battle fleets… and being easily moved and put into any relative position required, and thus permanently seen and well considered, every possible idea of a naval system could be discussed without the possibility of any dispute.” Using these models Clerk proposed the tactic of “cutting the line,” that Nelson employed at Trafalgar1)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clerk_of_Eldin. Nelson would quote from Clerk’s essay in his famous Trafalgar Memorandum.

When Roberts reported to Sir Percy Noble, commander of Western Approaches he explained that he intended to, “develop a game that would enable the British to understand why the U-boats were proving so successful in sea battles and facilitate the development of counter-tactics… The game would become the basis for a school, where those fighting at sea could be taught the tactics. With a few adjustments.. [the] wargame could be used for either analysis or training.”2)A Game of Birds and Wolves, p. 143 Not surprisingly, Roberts was met with skepticism and not a little bit of derision. As one who is constantly pitching the importance of wargames to the U. S. military I understand the uphill fight that Roberts was facing. British destroyer commanders definitely did not want to go to Liverpool to, “play a game.” But, since the orders had come directly from Churchill, Noble had little choice but to give Roberts the top floor of the Western Approaches HQ for his ‘game’. Roberts made a tactical mistake by referring to WATU’s ‘product’ (in modern bureaucratic parlance) as a ‘game’. I learned this early on in my career: never say the word ‘game’ if it can be avoided. Call what you’re working on a ‘simulation’. Chess is a game. Risk is a game. But I write simulations; and clearly what Roberts was working on was a simulation, too. (That said, the phrase, “game it out,” has now passed into the common idiom and is synonymous with ‘simulation’.)

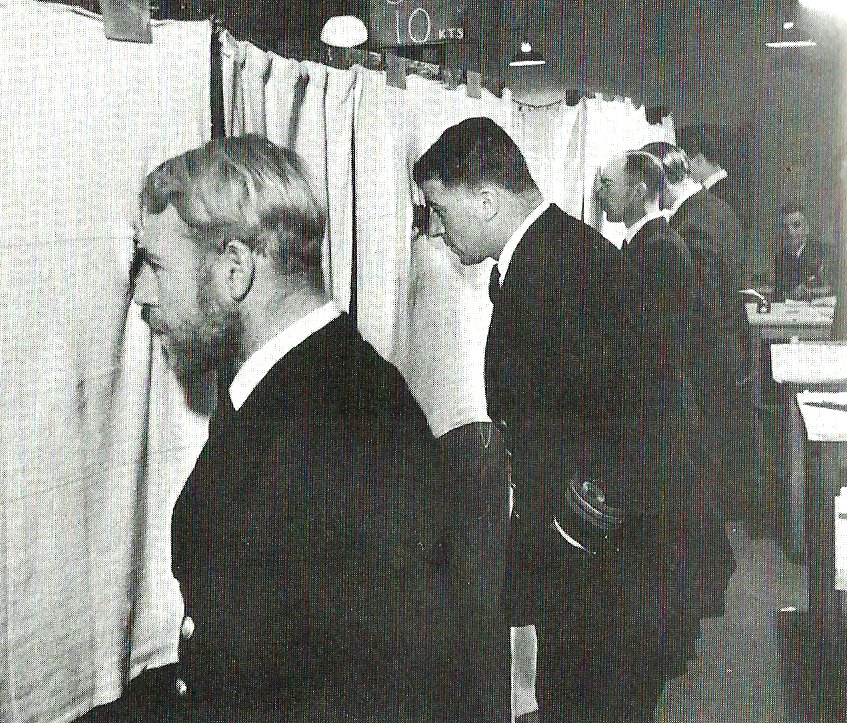

WATU simulated Fog of War by requiring the users to view the board through peep holes cut in canvas drapes. Submarine tracks (see above) were drawn in green chalk which, apparently, was not visible from the other side of the canvas sheets. The photo shows British destroyer commanders playing, “The Game,” and learning from the simulation. Photo from, “A Game of Birds and Wolves.”

In order to simulate Fog of War Roberts invented a system in which the destroyer commanders would view the board from behind a canvas sheet; their view of the battle restricted by peep holes cut in the canvas. Furthermore, submarine tracks were drawn with green chalk on the floor (see above photo) which, somehow, became invisible when viewed from the other side of the canvas. Consequently, the destroyer commanders had only a restricted view of the battle around them and were completely in the dark as to the simulated U-boats positions.

When Roberts began his work nobody in the British Admiralty knew U-boat tactics. Indeed, the German U-boat commanders were creating their tactics on the fly often ignoring the Kriegsmarine’s Memorandum for Submarine Commanders to fire torpedoes at no closer than 1,000 meters. U-boat ace, Otto Kretschmer was the first to insist that the most efficient way to attack convoys was to slip inside the destroyer screen, launch torpedoes at a range of about 500 meters, submerge and wait for the convoy to pass over them to make his escape ‘out the back’ of the convoy. Interestingly, this was the same technique that I discovered playing Sierra On Line’s Aces of the Deep.

One of the first scenarios that Roberts investigated using his new wargame was the battle of Convoy HG 76. This was a multi-day contest involving 32 merchant ships, 24 escorts and 12 U-boats. It was considered a great Allied victory because five U-boats were sank (though the Allies only knew of three at the time) and 30 merchant ships made it home safely. Assisted by WRENs Jean Laidlaw and Janet Okell, they replayed the historical situation hoping to understand Allied commander Captain Frederick John “Johnnie” Walker’s anti-submarine maneuver ‘Buttercup’. The Buttercup maneuver (named after Walker’s pet name for his wife) involved, “on the order Buttercup… all of the escort ships would turn outward from the convoy. They would accelerate to full speed while letting loose star shells. If a U-boat was sighted, Walker would then mount a dogged pursuit, often ordering up to six of the nine ships in his [escort] group to stay with the vessel until it was destroyed.”3)A Game of Birds and Wolves, p. 155

What confused Roberts was that the Allied merchant Annavore was torpedoed while in the center of the convoy. As he and the WRENs replayed the scenario they could not duplicate reality unless the U-boat had, “entered the columns of the convoy from behind. And it must have done so on the surface, where it was able to travel at a faster speed than the ships. By approaching from astern, where the lookouts rarely checked, the U-boat would be able to slip inside the convoy undetected, fire at close range, then submerge in order to get away.”4)The Game off Birds and Wolves. P. 158

Using the scenario of when the escorts actually sank a U-boat using the Buttercup maneuver it was determined that they had succeeded by only accidentally hitting a U-boat that was joining the attack on the convoy and not the actual U-boat who had made the attack that they were pursuing. This makes sense when you realize that the attacking U-boat had submerged immediately after the attack and was waiting for the remaining convoy to pass overhead while the escorts were running far outside the perimeter of the convoy looking for it.

In other words, Walker’s Buttercup maneuver was, in fact, a terrible anti-submarine tactic.

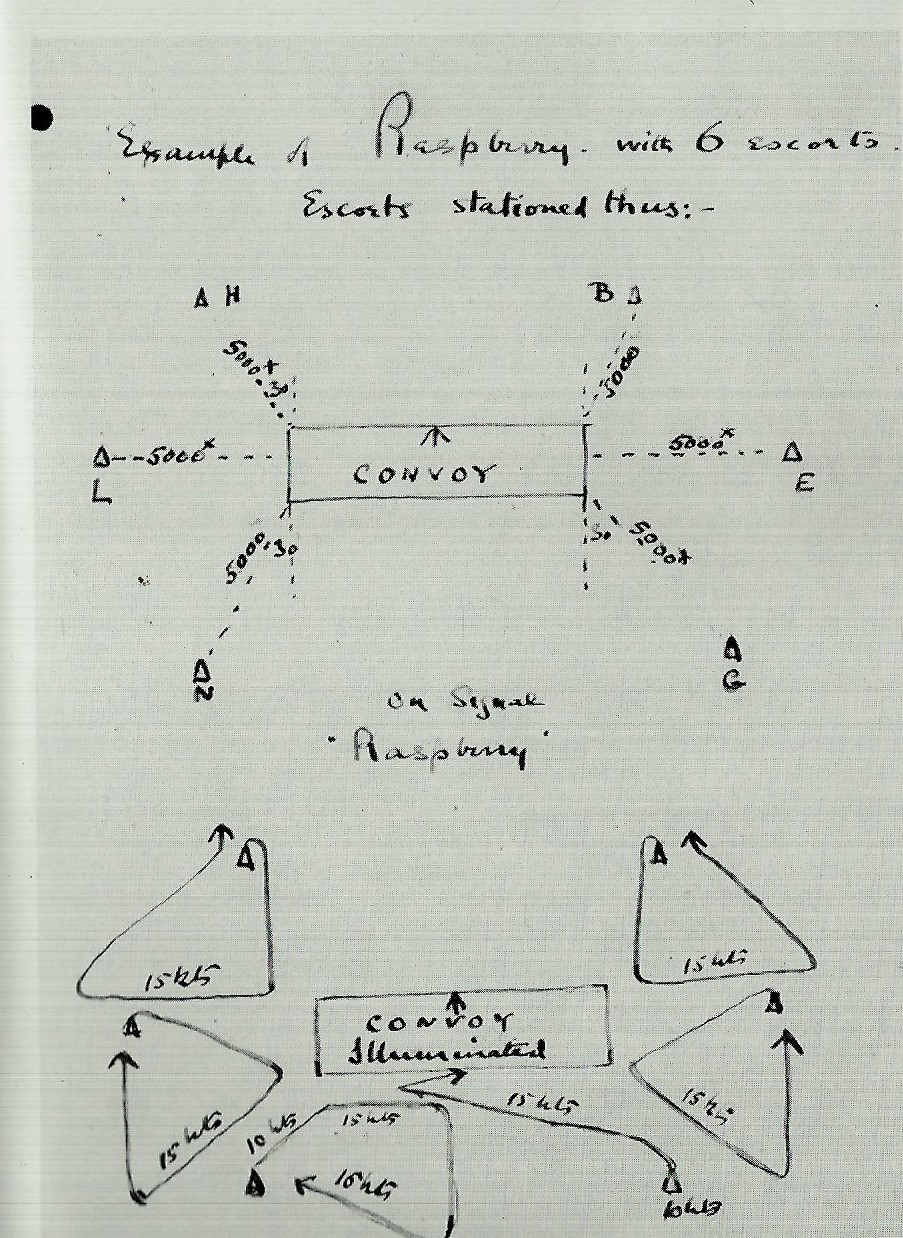

The ‘Raspberry Maneuver’, created from numerous runs of ‘The Game’ was determined to an effective anti-submarine tactic. Here it is drawn by Admiral Usborne. From the book, “A Game of Birds and Wolves.” Click to enlarge.

The first successful anti-submarine tactic to be invented using the Game as a test bed was, “Raspberry,” (so called by Wren Ladlaw as a ‘raspberry‘ to Hitler). As you can see from the above drawing, upon discovery of a U-boat or a torpedo hit, the escorts draw closer to the convoy, not the opposite as in Walker’s Buttercup maneuver. When Roberts and the WRENs ran a scenario for Western Approaches commander Noble and his staff, Noble – who at first was highly skeptical – was so impressed that he immediately sent a message to Churchill, “The first investigations have shown a cardinal error in anti-U-boat tactics. A new, immediate and concerted counter-attack will be signaled to the fleet within twenty-four hours.” 5)The Game of Birds and Wolves, p. 162 By summer of 1942, using these new maneuvers, U-boat losses had quadrupled. Eventually other anti-U-boat maneuvers were also developed by the WATU team and all Atlantic destroyer commanders were ordered to WATU to play, “The Game,” and learn the lessons.

Obviously, there were other improvements in anti-submarine warfare that also contributed to the Allies winning the Battle of the North Atlantic. Nonetheless, it is interesting to read about the proper application of simulations in wartime. I have long been an advocate of simulations to test, “what if” scenarios. Indeed, this has been the main focus of my professional career for thirty plus years. It’s still an uphill battle.