Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emmanuel Luetze. 1851. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Click to enlarge.

I must confess that I was never much a fan of George Washington’s generalship. Having not studied American Revolution military history I thought that from 1776-1781 the British chased Washington and his sad excuse for an army up and down the eastern seaboard of what was to become the United States until the French Comte de Grasse defeated the British naval forces at the Battle of the Chesapeake and the Comte de Rochambeau at the head of a French army surrounded, besieged and eventually captured, Cornwallis at Yorktown.

To make matters worse, years ago I stumbled upon George Washington’s Expense Account which is, frankly, brutal. Washington turned down the magnanimous salary of $500 a month for being Commander in Chief of the Continental Army famously saying,

“As to pay, Sir, I beg leave to Assure the Congress that as no pecuniary consideration could have temped me to have accepted this Arduous employment (at the expense of my domesttic [sic] ease and happiness) I do not wish to make any Proffit [sic] from it. I will keep an exact Account of my expences. Those I doubt not they will discharge, and that is all I desire.” 1)George Washington’s Expense Account, Washington, George & Kitman, Marvin, page 15

If Washington had accepted the salary he would have been paid $48,000 for five years’ service. Instead, his ‘expences’ came to $449,261.51! This book – and it contains a photocopy of every page of Washington’s Expense Account in fine copperplate handwriting along with a humorous explanation of the expense – is damning. Washington’s very first entry for June, 1775 was for $6,214 (over an entire year’s salary at $500 per month) for “…the purchase of five Horses… to equip me for my journey to the Army at Cambridge – & for the Service I was Then going upon – having sent my Chariot and Horses back to Virginia.” There are also numerous expenses for cases of the finest wines and plenty of food while at Valley Forge. Not surprisingly, when Washington offered Congress the same terms when he was elected president (no salary just expenses) Congress insisted that he take $25,000 a year; no expenses paid.

Like most Americans, what little knowledge I had of the battle of Trenton can be summed up in Luetze’s famous painting, above: Washington, posed heroically, crossed the Delaware River on Christmas Eve and surprised a garrison of drunken Hessian mercenaries at Trenton capturing them all without a shot. In reality, not much of that is true. Yes, Washington did attack Trenton but it was on the morning of December 26, 1776, and the Hessians weren’t drunk; they fought bravely and their commander, Col. Johann Gottlieb Rall, died leading them.

Then I discovered (from reading David Hackett Fischer’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington’s Crossing) that the amazing part of the story wasn’t the battle of Trenton (which really was an extraordinary tale of a small, poorly-equipped, non-professional army making an audacious amphibious crossing of an ice-choked river) but the campaign that followed the victory from December 30, 1776 to January 3, 1777.

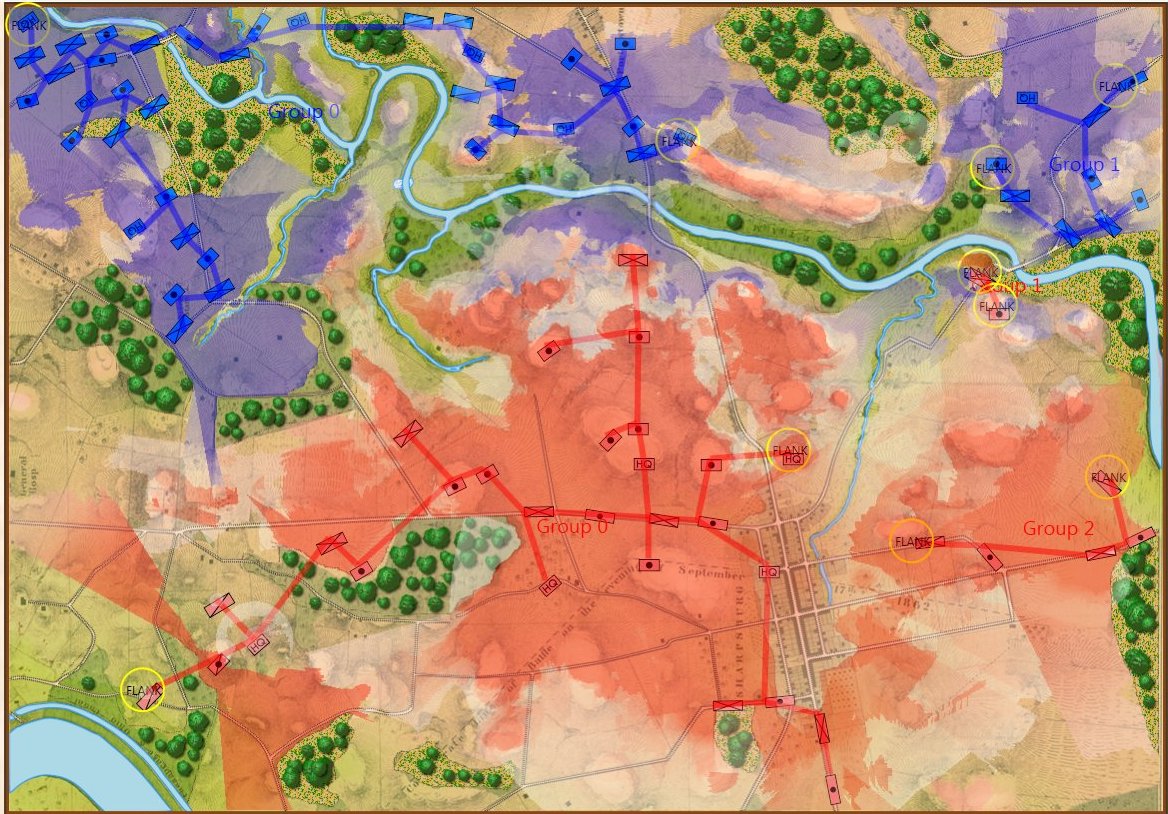

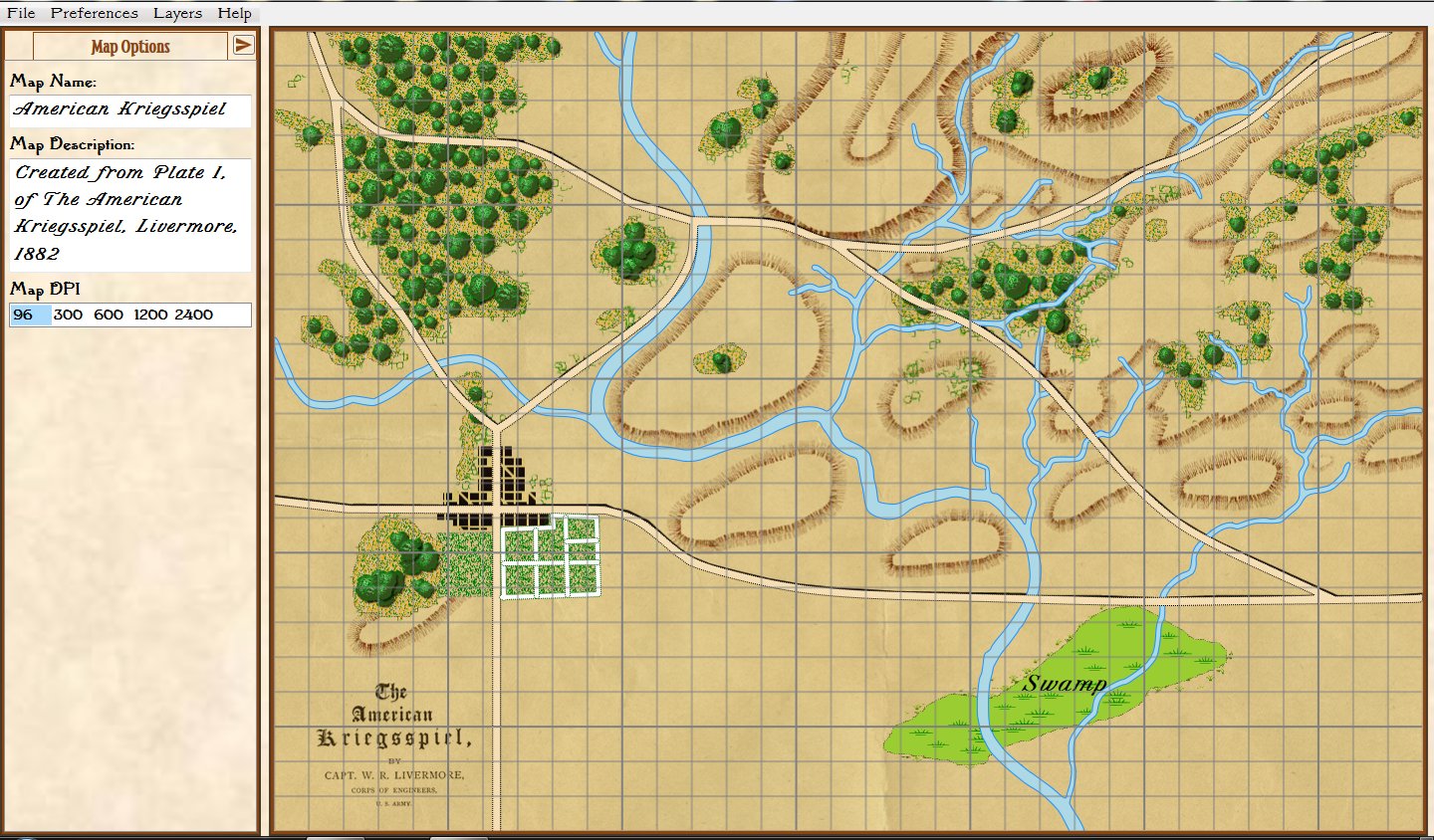

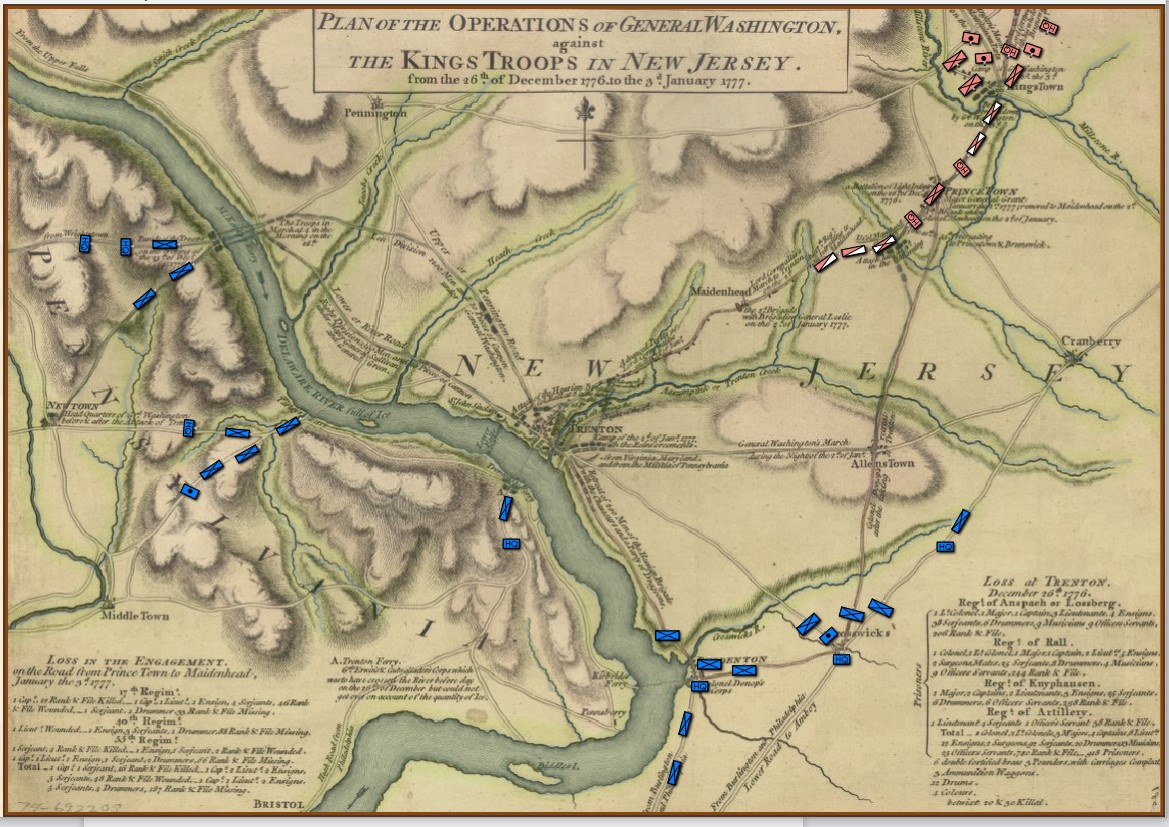

The strategic situation in the Princeton / Trenton area, December 29, 1776. Screen shot from the General Staff Scenario Editor. Click to enlarge.

Washington’s forces had made it safely back across the Delaware River after the Trenton raid but he now faced a difficult decision: terms of enlistment were running out for many units in his army and he feared taking the field again in bitter cold with a diminished force. As always, Washington held a council of war. As the senior commanders of the army advised caution a courier arrived informing them that Brigadier General John Cadwalader with his Pennsylvania militia had already crossed the Delaware and was at Crosswicks itching for a fight with the British (this is the blue force at the bottom of the map, above). After more discussion, one group stated, “tho’ they would not have advised the Movement, yet it being done it ought to be supported.”2)Washington’s Crossing, David Hackett Fischer page 266. Eventually, with Washington’s urging, the council voted to support Cadwalader, recross the Delaware and, again, defeat the British in the field.

This was a bold strategy; a defeat of the Continental Army with its back to a river would probably spell the end of the revolution. Washington’s plan was to assemble his forces east of Trenton, in a strong defensive position on ‘good ground’ behind the Assunpink Creek and lure Cornwallis, who was commanding the British and Hessian forces, to attack. This Cornwallis did and was soundly defeated. Washington now moved decisively, sending his forces to capture Prince Town (Princeton) to the north. At the crucial moment in this battle Washington rallied the routed Pennsylvania forces saying, ” ‘Parade with us, my brave fellows! There is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly.’ Washington [then] led his men straight into the center of the battle, within thirty paces of the British line. He was mounted on a white horse, an easy mark for any British soldier.”3)Ibid. page 334

Frankly, I cannot comprehend such bravery. The attack, of course, was a success and the Americans captured Princeton and, perhaps more importantly, demonstrated that their volunteer army would fight, could fight and could win. Washington showed superb strategic and tactical vision throughout these ten crucial days4)See https://tencrucialdays.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/eb14b5212fb62dfea8d100f3efd1950f.pdf for a wonderful series of maps that cover this campaign as well as extraordinary personal courage.

I was wrong about George. Washington.

References

| ↑1 | George Washington’s Expense Account, Washington, George & Kitman, Marvin, page 15 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Washington’s Crossing, David Hackett Fischer page 266 |

| ↑3 | Ibid. page 334 |

| ↑4 | See https://tencrucialdays.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/eb14b5212fb62dfea8d100f3efd1950f.pdf for a wonderful series of maps that cover this campaign |