The goal of my doctoral research was to create a suite of algorithms that were capable of making ‘human-level’ tactical and strategic decisions. The first step is designing a number of ‘building block’ algorithms, like the least weighted path algorithm that calculates the fastest route between two points on a battlefield while avoiding enemy fire that we saw in last week’s post. Another important building block is Kruskal’s Minimum Spanning Tree algorithm which allows the computer to ‘see’ lines of units.

I use terms like ‘see’ and ‘think’ to describe actions by a computer program. I am not suggesting that current definitions of these terms would accurately apply to computer software. However, it is simply easier to write that a computer ‘sees’ a line of units or ‘thinks’ that this battlefield situation ‘looks’ similar to previously observed battlefields. What is actually happening is that units are represented as nodes (or vertices) in a a graph and some basic geometry is being applied to the problem. Next week we will use probabilities. But, at the end of the day, it’s just math and computers, of course, don’t actually ‘see’ anything.

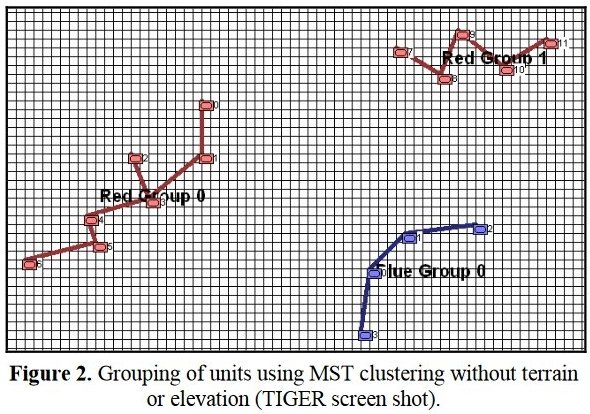

Examples of how Kruskal’s Minimum Spanning Tree algorithm can be used to separate groups of units into cohesive lines. These figures are taken from, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. & Segre, A. M.

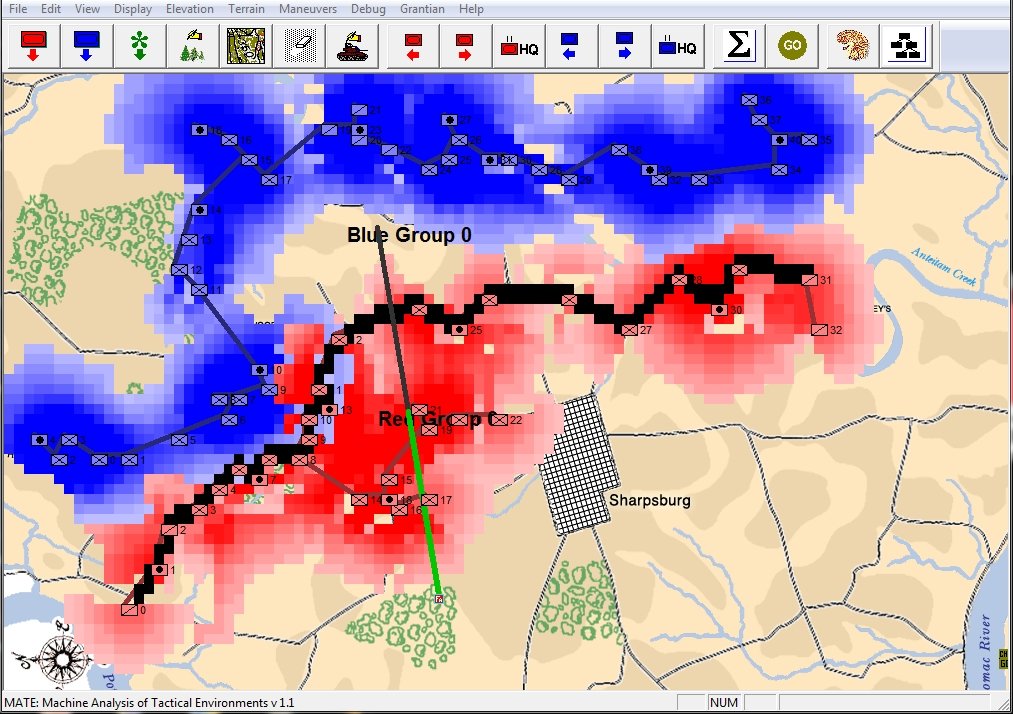

When you and I look at a map of a battle we immediately see the opposing lines. We see units supporting each other, interior lines of communication, and lines of advance and retreat. The image, below, shows how the program (in this case, TIGER, the Tactical Inference Generator which was written to demonstrate my doctoral research) ‘sees’ the forces at the battle of Antietam. The thick black line is the ‘MST Spine’. You and I automatically perceive this as the ‘front line’ of the Confederate forces, but this is a visual representation of how TIGER calculates the Confederate front line. Also important is that TIGER perceives REDFOR’s flanks as being anchored (that is to say, BLUE does not have a path to the flanking objective, the tip of the green vector, that does not go through RED Range of Influence, ROI, or Zone of Control).

TIGER screen shot of ‘flanking attribute’ calculations for the battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862, 0600 hours). Note the thick black line that represents the MST spine of REDFOR Group 0, the extended vector that calculates the Flanking Goal Objective Point and BLUEFOR and REDFOR ROI (red and blue shading). REDFOR (Confederate) has anchored flanks. From, “Algorithms for Generating Attribute Values for the Classification of Tactical Situations,” by Sidran, D. E. & Segre, A. M.

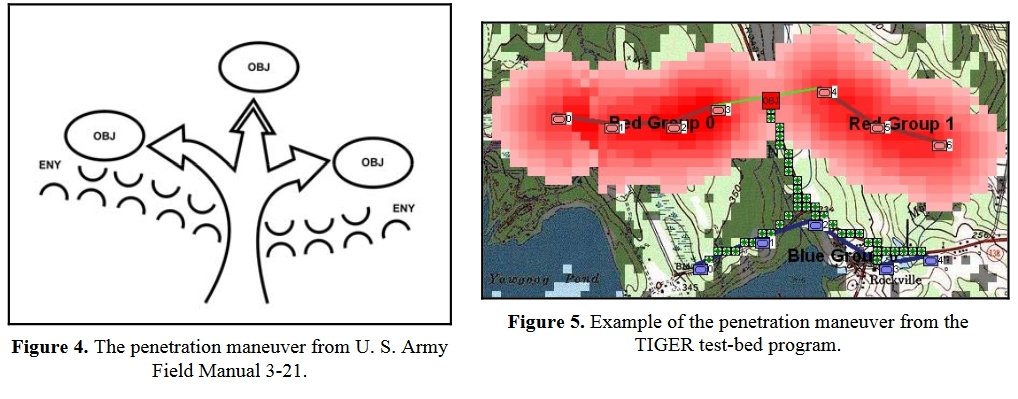

Now that TIGER can see the opposing lines and recognize their flanks we can calculate the routes for implementing the Course of Action (COA) for various offensive maneuvers. U. S. Army Field Manual 3-21 indicates that there are five, and only five, offensive maneuvers. The first is the Penetration Maneuver (note: the algorithms for these and the other maneuvers appear in, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. and Segre, A. M.) and can be downloaded from ResearchGate and Academia.edu.

The Penetration Maneuver is described in U.S. Army Field Manual 3-21 and as implemented by TIGER. Note how TIGER calculates the weakest point of REDFOR’s line. From, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. and Segre, A. M. Click to enlarge.

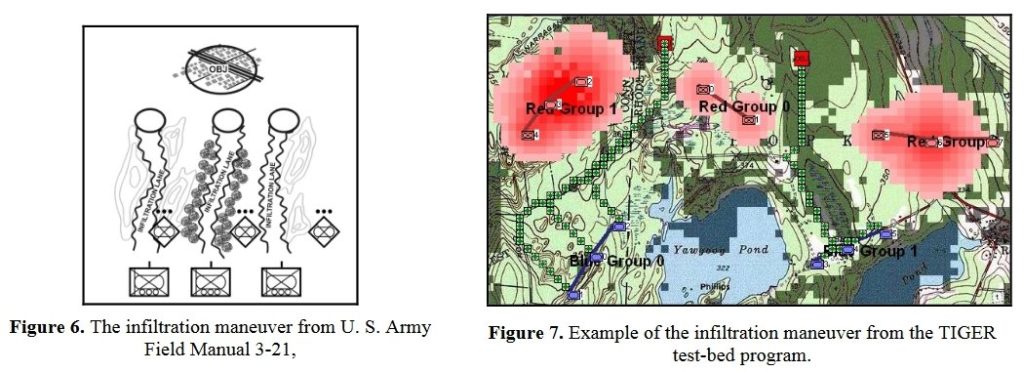

The next maneuver is the Infiltration Maneuver. Note that to implement the Infiltration Maneuver, BLUEFOR must be able to infiltrate REDFOR’s lines without entering into RED’s ROI:

The Infiltration Maneuver as described in U.S. Army Field Manual 3-21 and as implemented by TIGER. Note how TIGER reaches the objectives without entering into REDFOR ROI. From, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. and Segre, A. M. Click to enlarge.

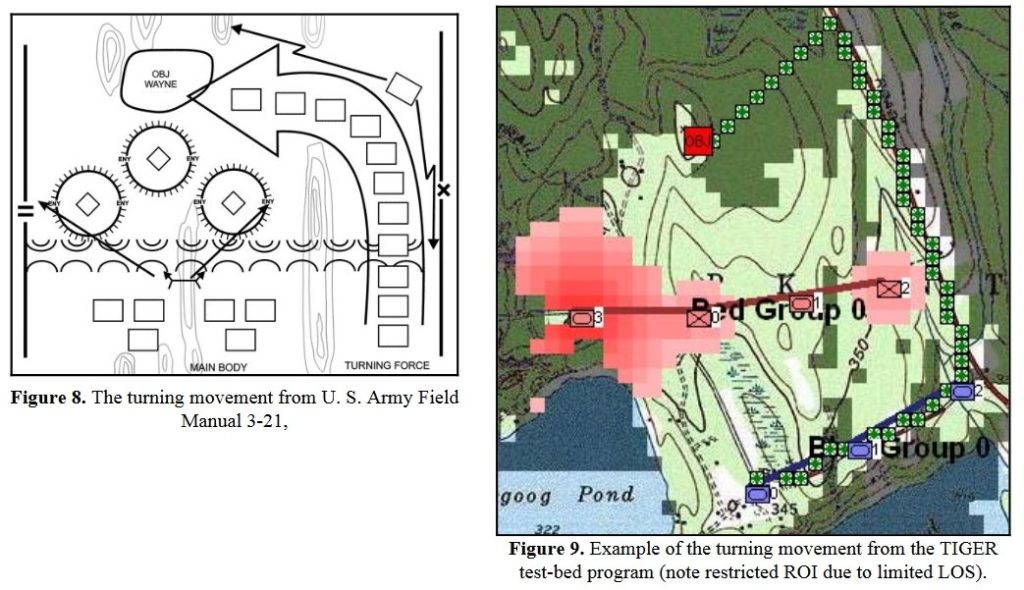

The next maneuver is the Turning Maneuver. Note: in order to ‘turn an enemy’s flanks’ one first must be able to recognize where the flanks of a line are. This is why the earlier building block of the MST Spine is crucial.

The Turning Maneuver as illustrated in U. S. Army Field Manual 3-21 and in TIGER. From, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. and Segre, A. M. Click to enlarge.

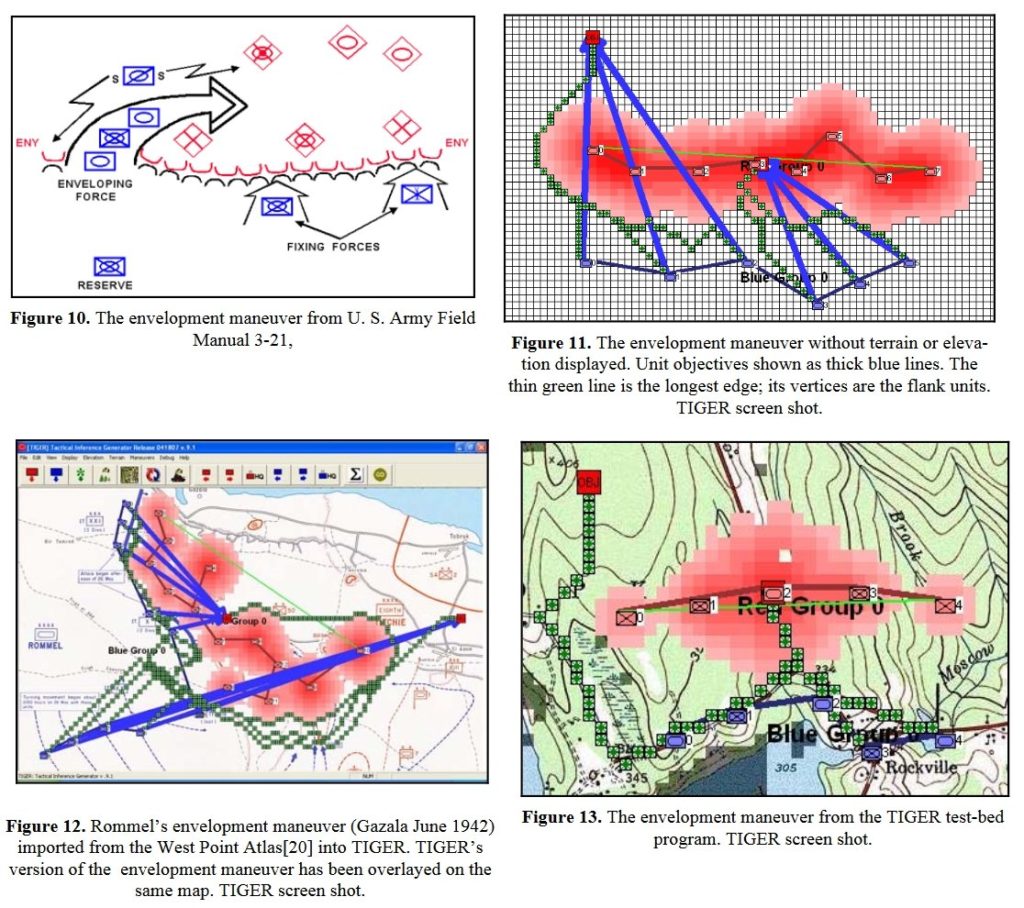

Certainly the most complex offensive maneuver is the Envelopment Maneuver which requires two distinct movements and calculations for the attacking forces: first the attacker must decide which flank (left or right) to go around and then the attacker must designate a portion of his troops as a ‘fixing force’. Think of an envelopment maneuver as similar to the scene in Animal House when Eric “Otter” Stratton (played by Tim Matheson) says to Greg Marmalard (played by James Daughton), “Greg, look at my thumb.” Greg looks at Otter’s left thumb while Otter cold-cocks Marmalard with a roundhouse right. “Gee, you’re dumb,” marvels Otter. In an envelopment maneuver the fixing force is Otter’s left thumb. Its purpose is to hold the attention of the victim while the flanking force (the roundhouse right) sweeps in from ‘out of nowhere’. In the next post I will show a real-world example of an Envelopment Maneuver created by my MATE (Machine Analysis of Tactical Environments) program for DARPA.

The Envelopment Maneuver as shown in U. S. Army Field Manual 3-21 and as implemented in TIGER. From, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. and Segre, A. M. Click to enlarge.

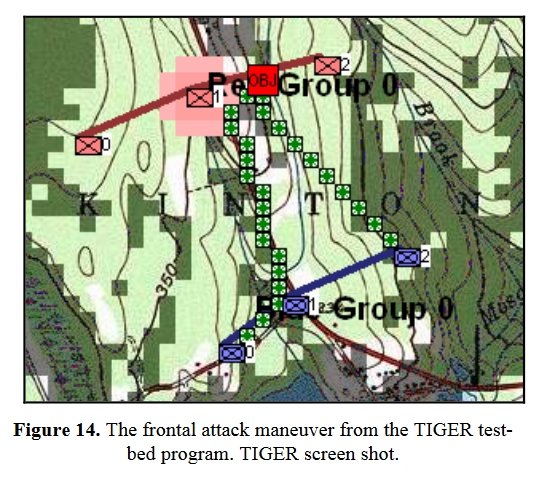

Lastly, and obviously the maneuver of last resort, is the Frontal Assault:

The Frontal Assault Maneuver from, “Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.” by Sidran, D. E. and Segre, A. M. Click to enlarge.

All that I’ve done in this post is show some of the things that the TIGER program does. What I haven’t done is show how the algorithms work and that’s because they are described in the papers, below. Obviously, this is a subject that I find pretty interesting, so feel free to ask me questions (you can use the Contact Us page).

It is my intention to incorporate these algorithms into the General Staff wargame. However, I’ve been told by a couple of game publishers that users don’t want to play against a human-level AI. What do you think? If you’ve read this far I would really appreciate it if you would answer the survey below.

[os-widget path=”/drezrasidran/survey-11-27″ of=”drezrasidran” comments=”false”]

Papers that were cited in this post with download links:

“An Analysis of Dimdal’s (ex-Jonsson’s) ‘An Optimal Pathfinder for Vehicles in Real-World Terrain Maps'”

“Algorithms for Generating Attribute Values for the Classification of Tactical Situations.”

“Implementing the Five Canonical Offensive Maneuvers in a CGF Environment.”

Your maths all looks good. Clearly you have done more work on it than I have, but after giving it consideration I really doubt that you can apply reasoning to the AI. The sort of reasoning that would allow an AI to adjust a defensive line rather than advance. Reasoning required to pull bluff’s or take calculated wild chances. In particular modelling to reflect the outrageous chances of war where units win because of small details. i recently studied a battle where a small platoon or squad of troops crossed a body of water in old boats, were spotted, but still managed to storm the beach and route heavily entrenched company positions. The same follies that led the Argentinians to surrender at Goose Green. To decribe your AI as human level is a bit rich in my opinion but I would happily be prooved wrong. However, your equations are nothing but simple algorithms for the obvious, getting from one place to another, ‘seeing’ the enemy. Theres nothing there coverng reasoning. THAT IS TRUE AI.

As we will see next week when I show my doctoral research we determine human-level by asking a computer program to predict what the human will do in tactical situations. If the program answers correctly a statistically significant number of times then we have created an AI that is, indeed, capable of human-level decisions.

You may also like to take a look at some ‘real world tactical reasoning’ for the battle of Marjah here: http://www.riverviewai.com/

“users don’t want to play against a human-level AI. ”

I find this statement pretty amazing. One of the big reasons why I don’t play computer wargames is because of the pathetic AI. The only way for the game to be challenging is for the computer to ‘cheat’. The computer’s production is higher. It bumps up their combat values. It moves them a little farther.

Why would publishers say that? How do they know that is what users want? Do users really want that? Why would they? This almost sounds like an excuse because they don’t know how to program a computer to do AI well.

It is easy to cheat some numbers in a game. Very hard to program a computer to ‘see’ and ‘think’.

Don’t get me started on cheating AI! I could name a very famous wargame designer. But, yes, that was verbatim what I was told by two ‘very big’ digital wargame publishers.

Thank you for your comment!