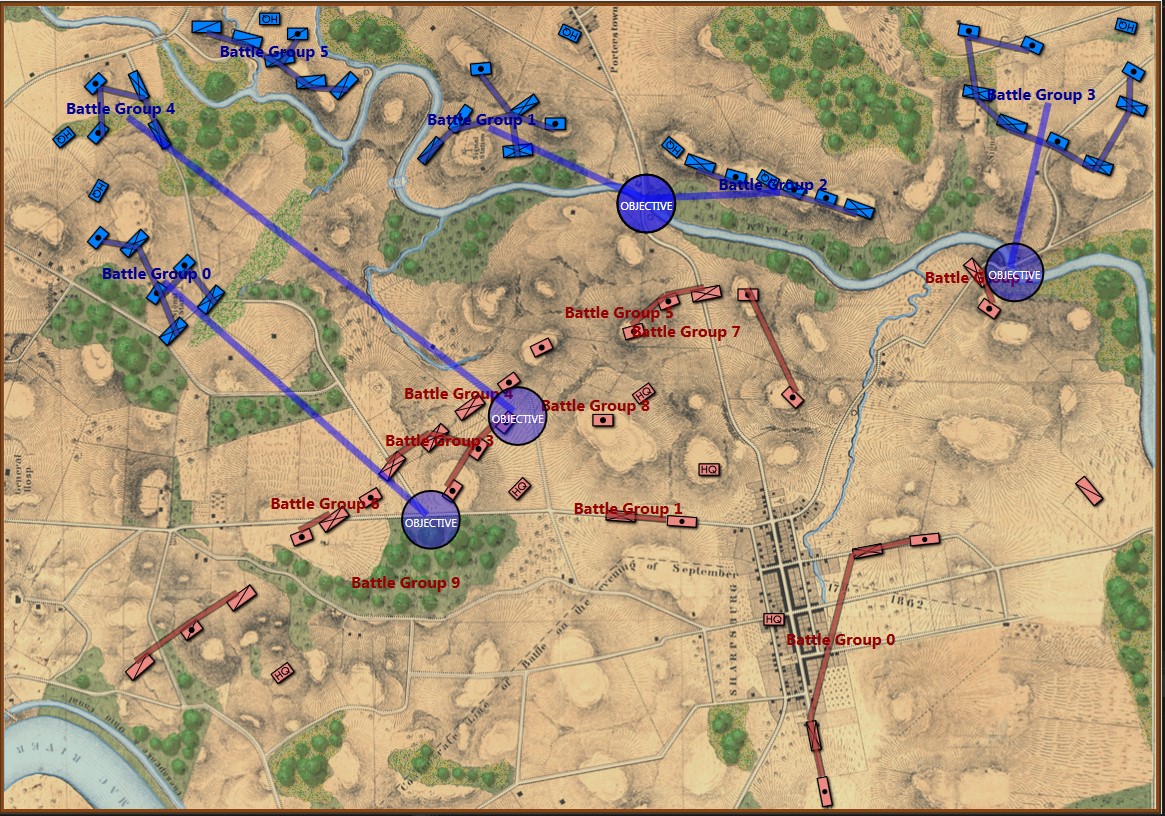

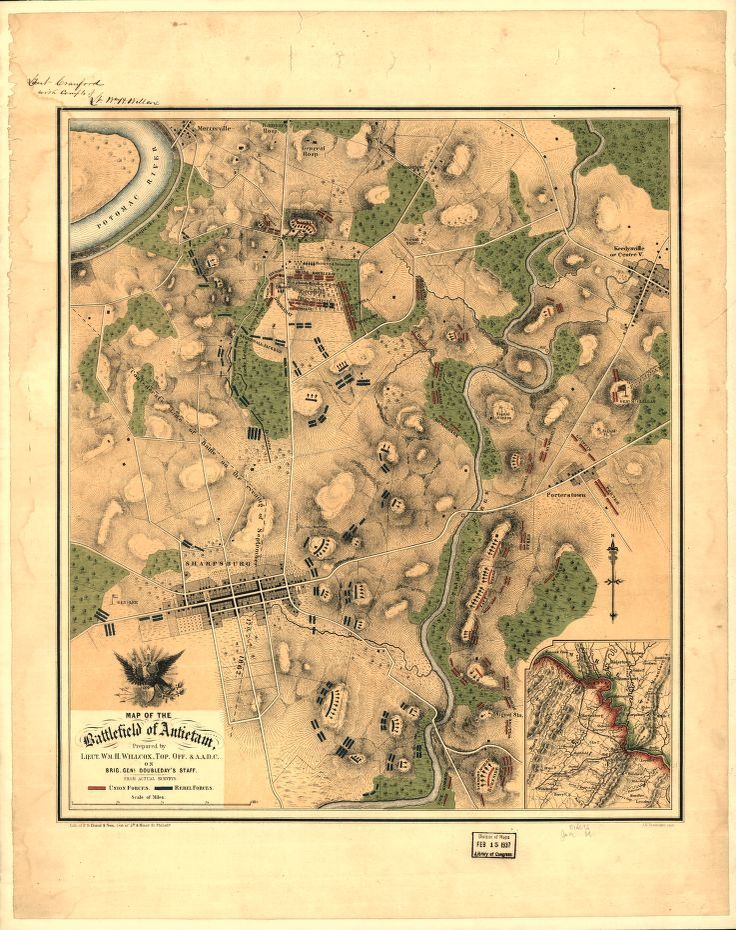

“Map of the battlefield of Antietam,” by William H. Willcox. Published in Philadelphia. Lithograph of P. S. Duval and Son, 1862. From the US Library of Congress.

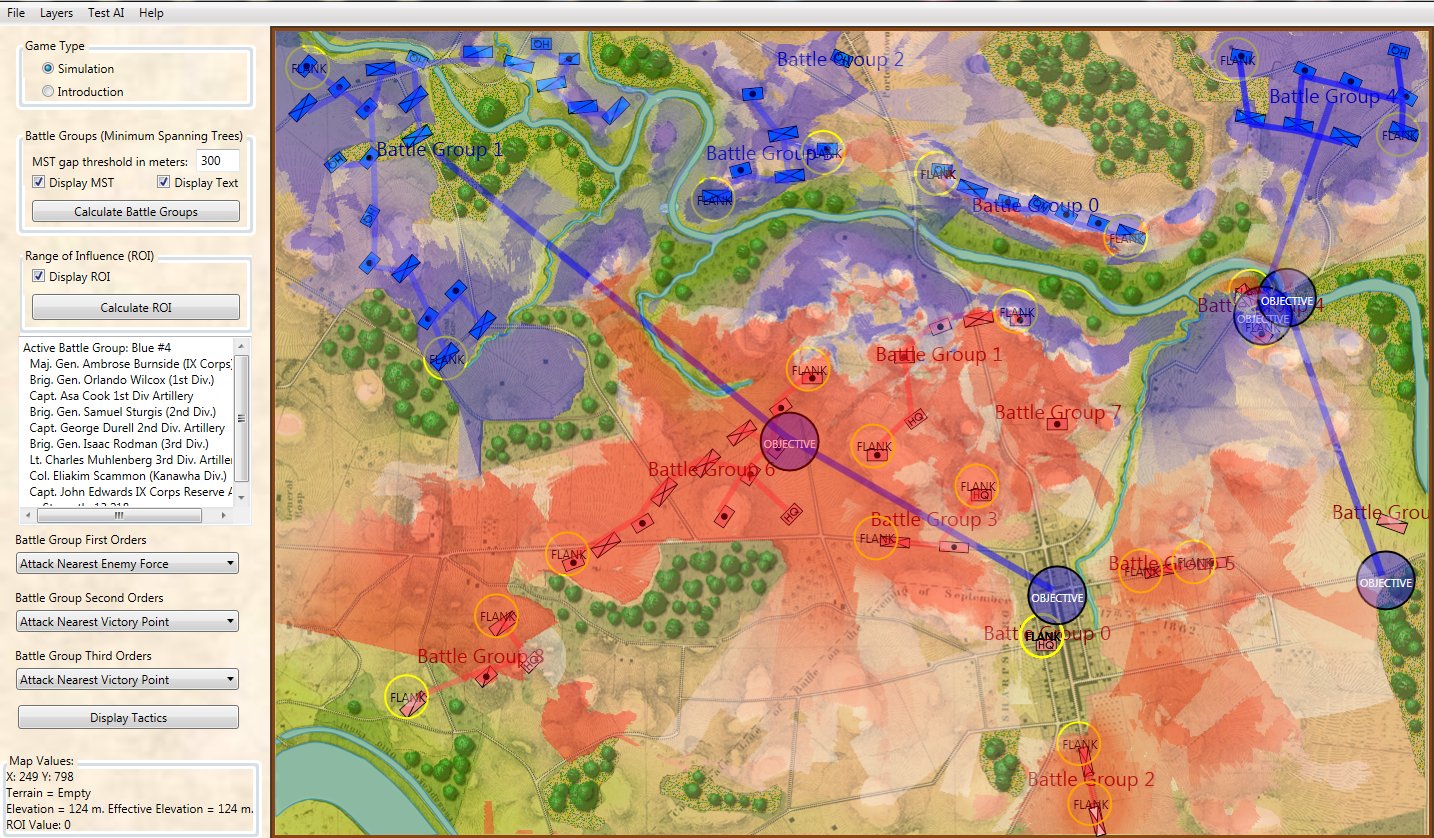

There are many reasons that I am intensely interested in this particular American Civil War battle fought on less than twenty square miles wedged in between the Potomac River and Antietam Creek. The battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862) exhibits a number of significant battlefield attributes which I use as base line cases to test algorithms used in creating a human-level tactical artificial intelligence 1)MATE: Machine Analysis of Tactical Environments. Specifically, Antietam definitively demonstrates 2)see http://riverviewai.com/download/SidranThesis.pdf the following attributes:

- Choke Points

- Anchored Flank

- Interior lines of communication

- Exterior lines of communication

- Restricted Avenue of Retreat

- Restricted Avenues of Attack

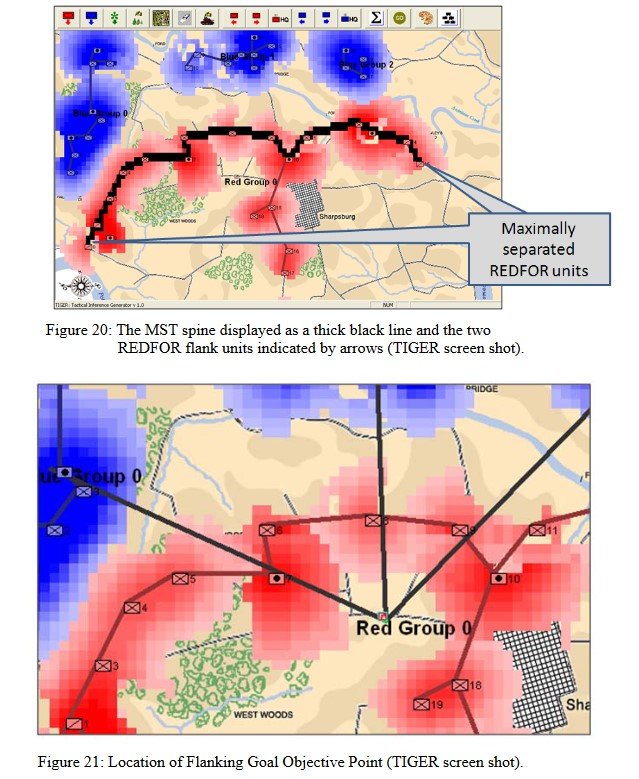

For example, in a blind survey of Subject Matter Experts (SMEs), it was overwhelmingly agreed that the RED (Confederate) left flank at the battle of Antietam exhibited the attribute of ‘anchored flank‘ 3)a flank that is attached to or protected by terrain, a body of water, or defended fortifications. and other positions, such as RED’s (Russian and Austrian) left flank at Austerlitz SMEs overwhelmingly agreed that the flanks do not exhibit the attribute of ‘anchored’ and are, therefore, unanchored. Once we have an example of an anchored flank and another example of an unanchored flank we can begin testing algorithms to detect the attribute of an anchored flank.

In my doctoral thesis (above) I demonstrated the algorithm 4)see pages 45-6 http://riverviewai.com/download/SidranThesis.pdf for detecting the attribute of anchored and unanchored flanks. I have made a number of substantial improvements to the original algorithm since then which are now incorporated into the current MATE.

In my doctoral thesis (above) I demonstrated the algorithm 4)see pages 45-6 http://riverviewai.com/download/SidranThesis.pdf for detecting the attribute of anchored and unanchored flanks. I have made a number of substantial improvements to the original algorithm since then which are now incorporated into the current MATE.

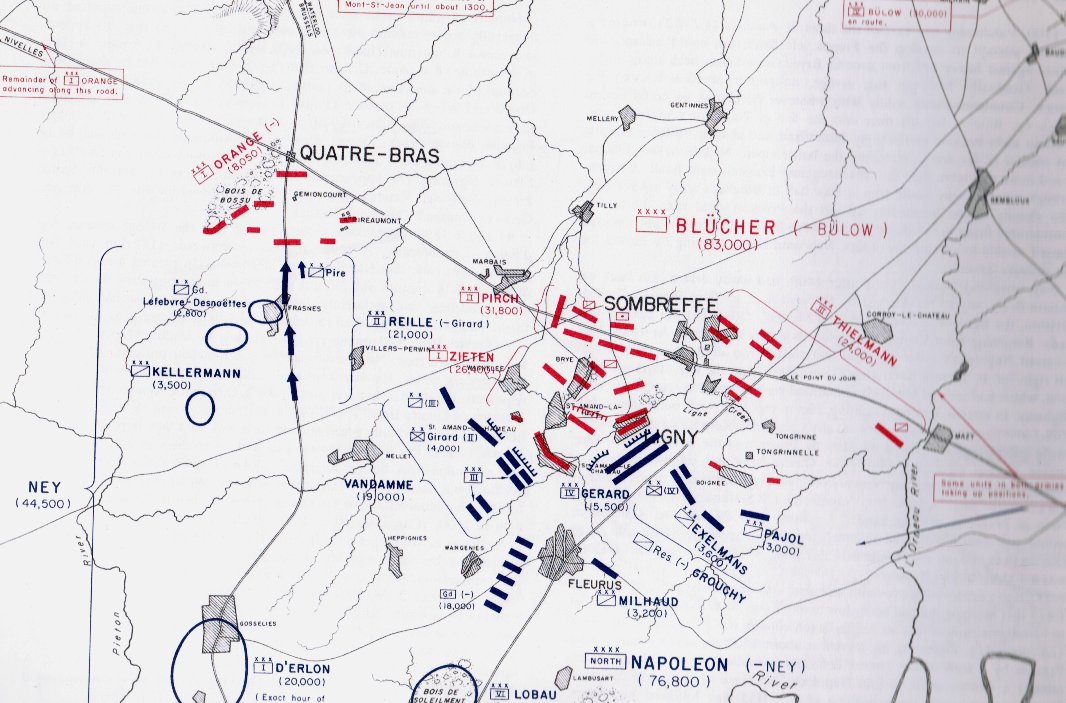

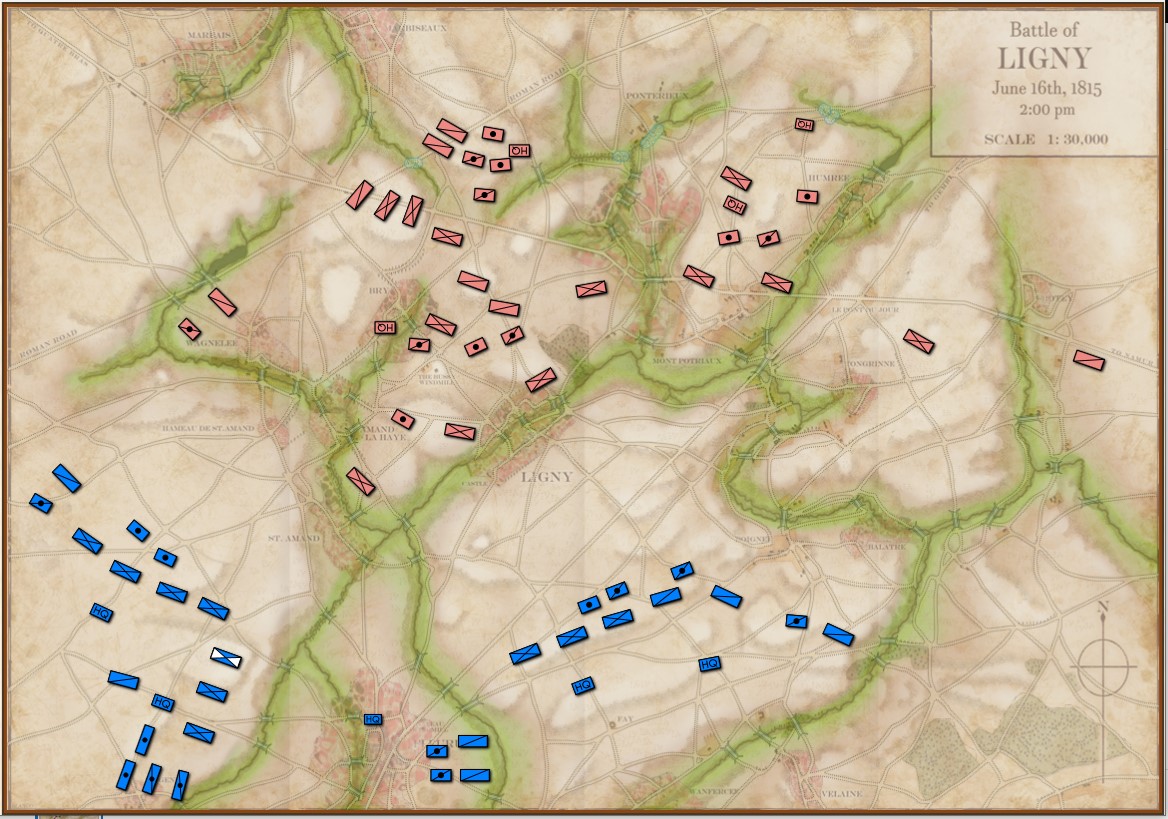

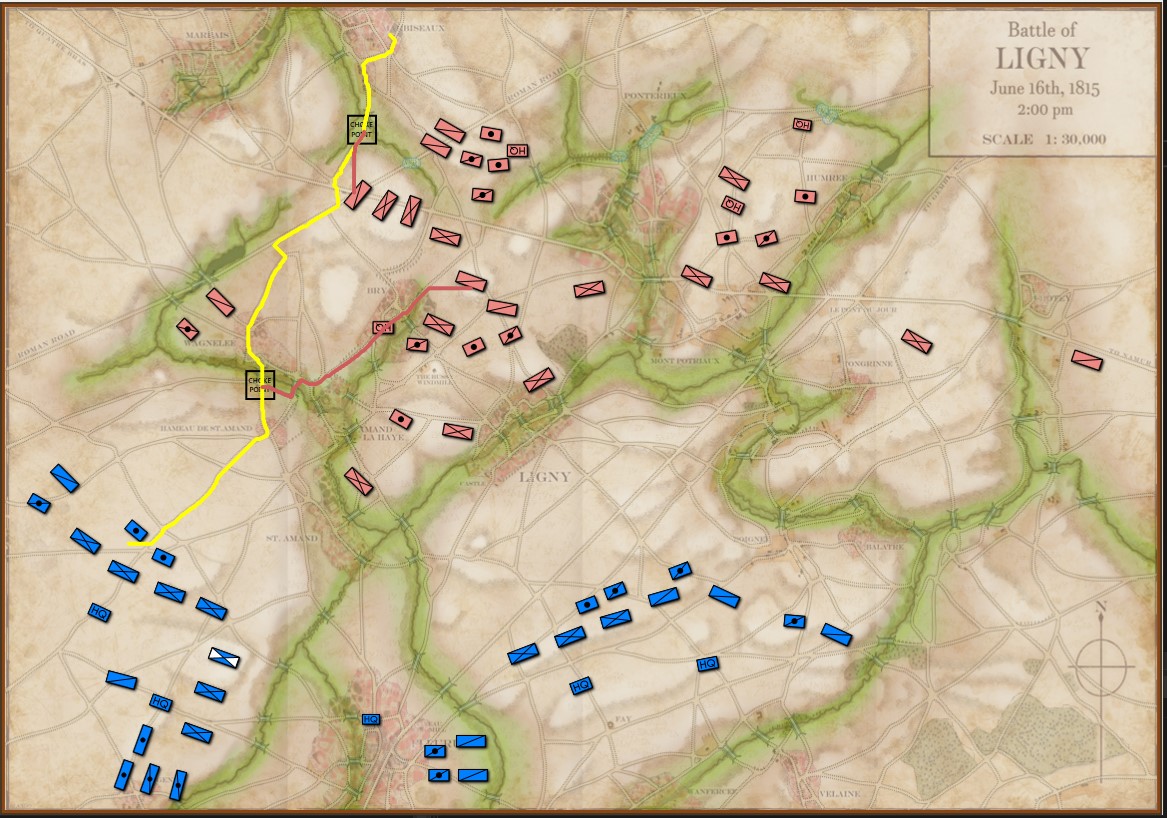

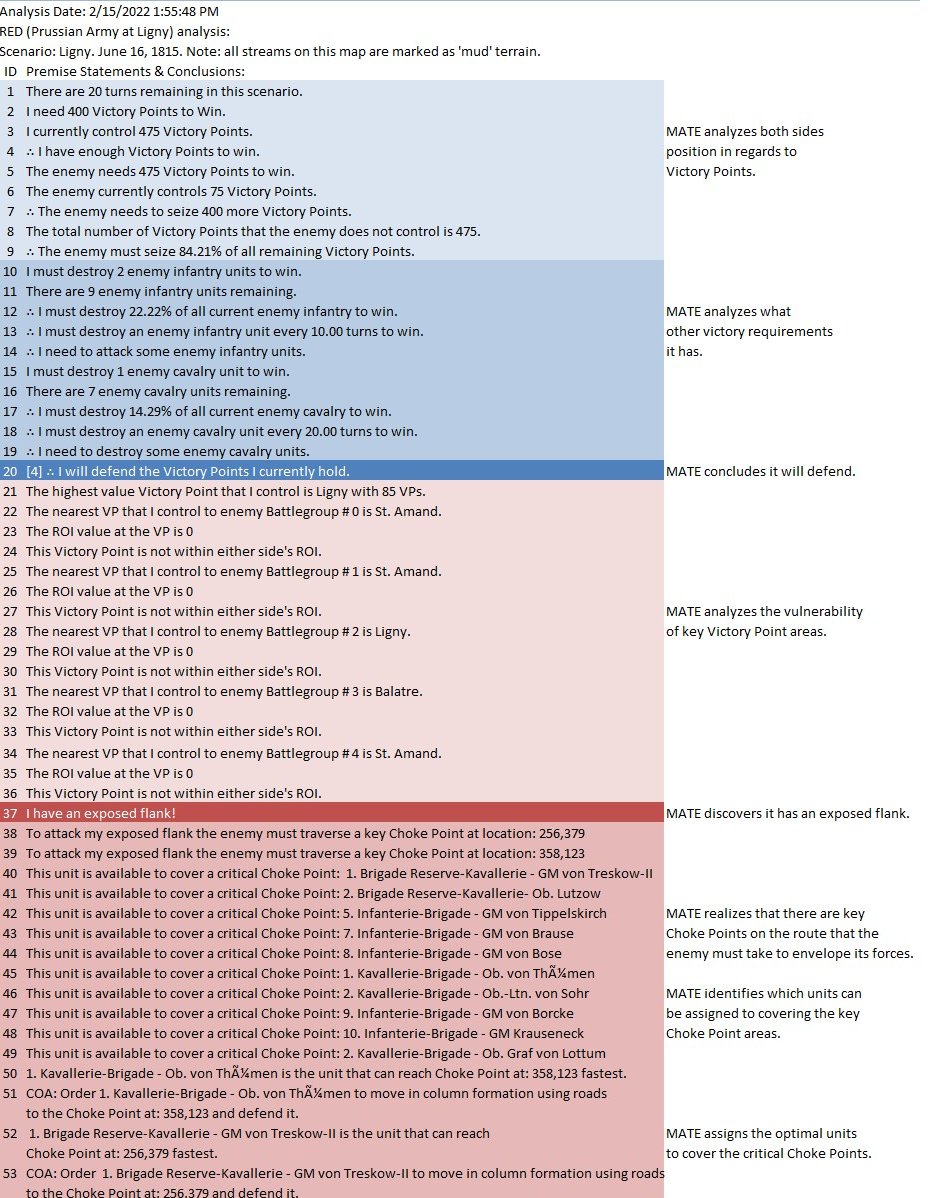

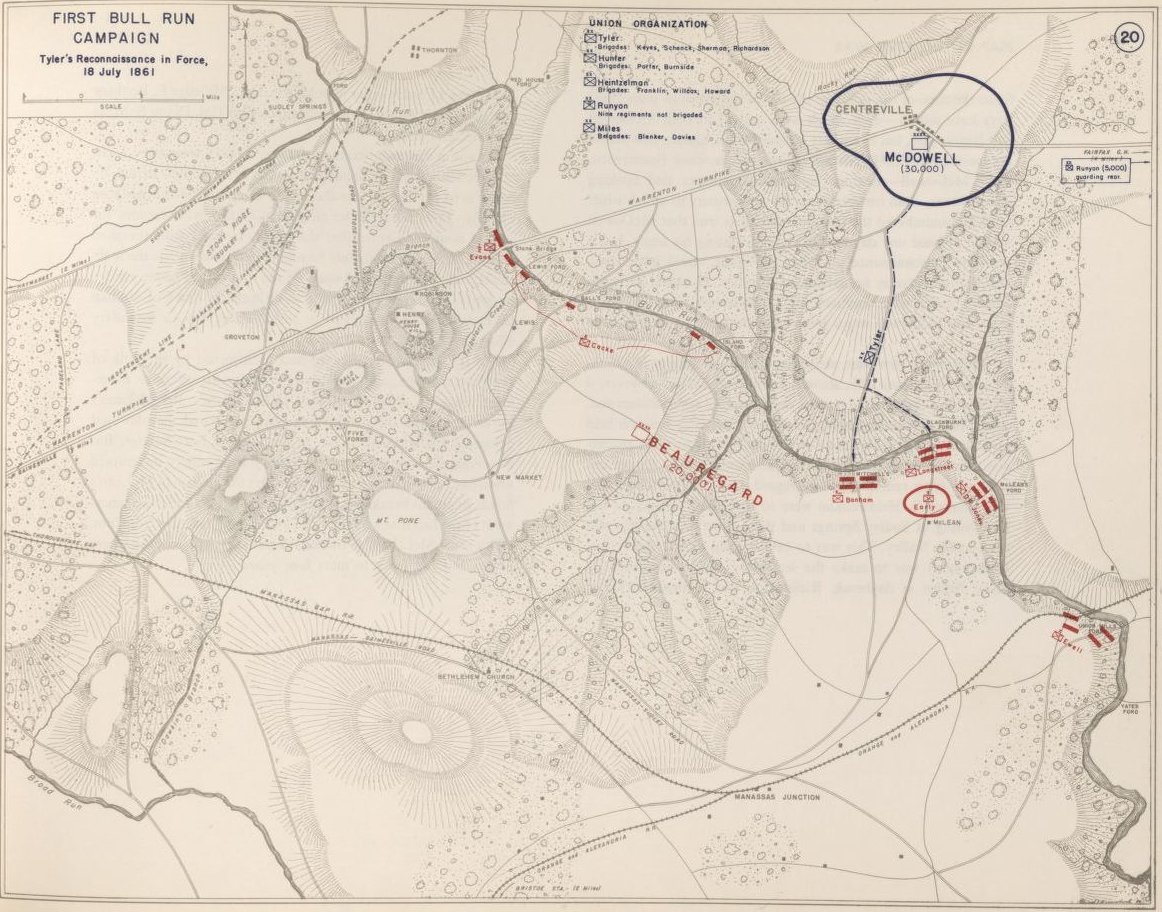

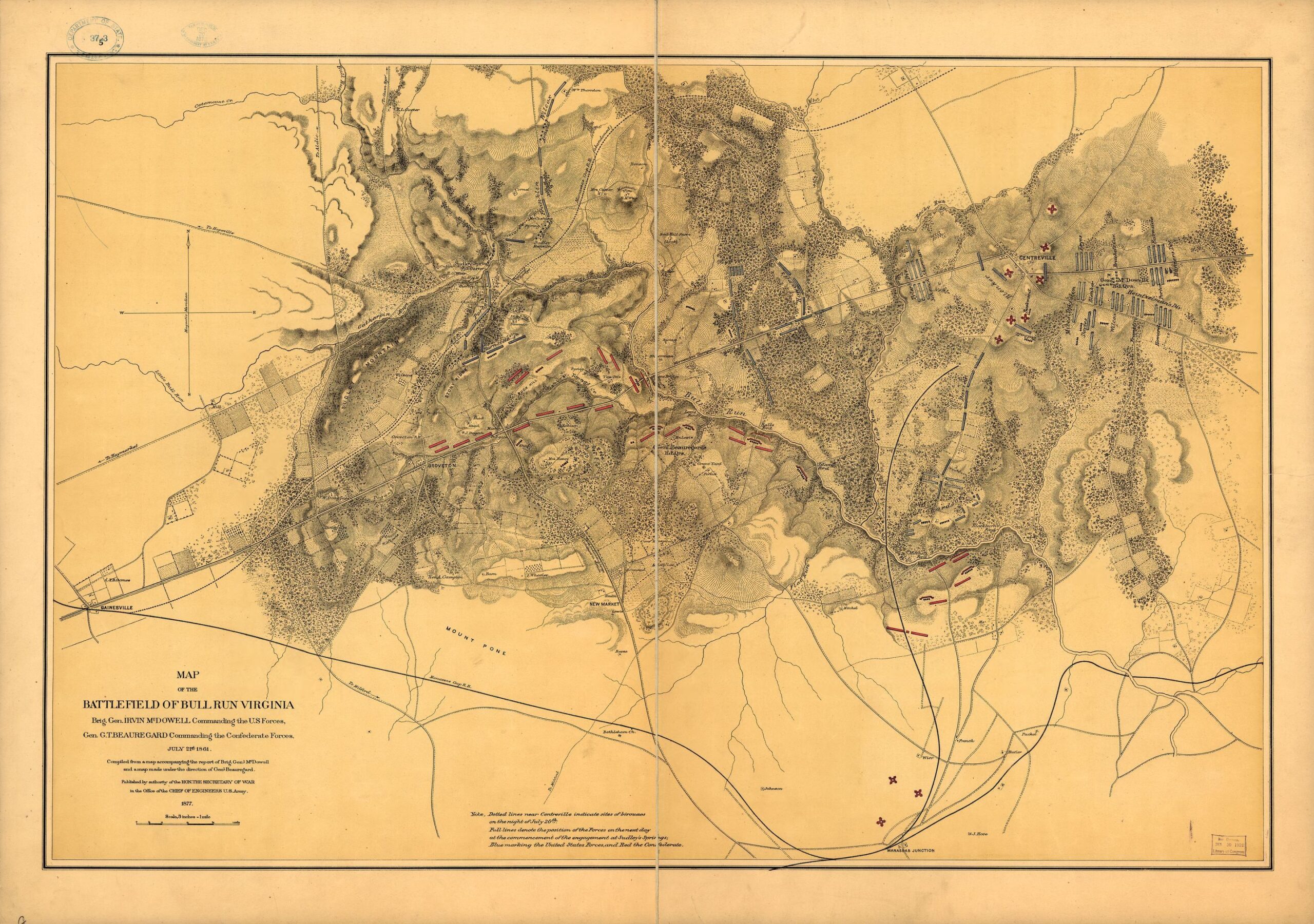

We have recently posted analyses of other battles that did not exhibit the attribute of an anchored flank (Ligny and 1st Bull Run, or Manassas). MATE correctly recognized that Ligny and Manassas do not have these attributes.

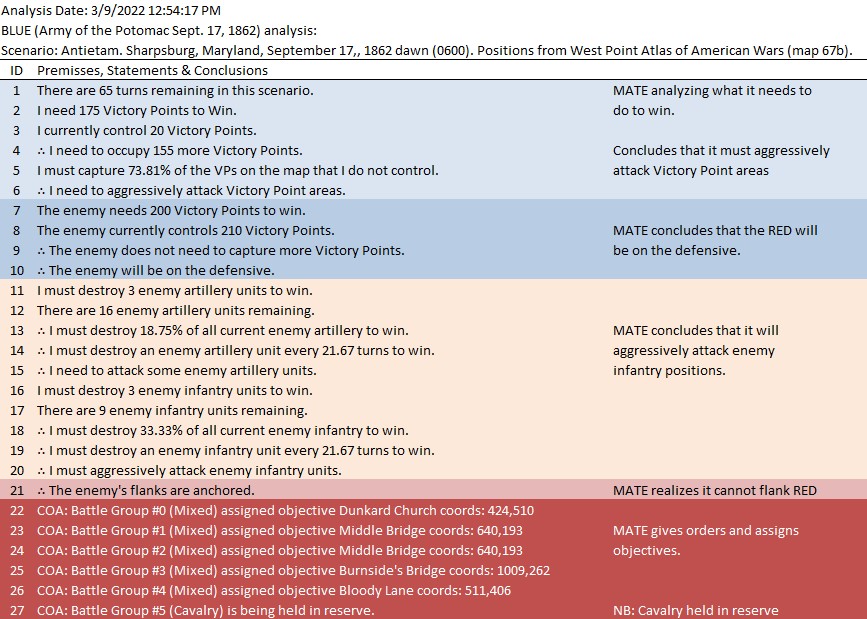

The tactical situation for Blue at Antietam is quite different than Blue’s positions at Ligny and Manassas (is it not curious how often Blue is the attacker in wargames?). The key difference, of course, is the lack of an open flank to attack. MATE will always attack an open flank if it can. Without an obvious objective, like an exposed flank, MATE will next look at opportunities to fulfill victory conditions. For Antietam, as Blue, MATE sees the situation like this:

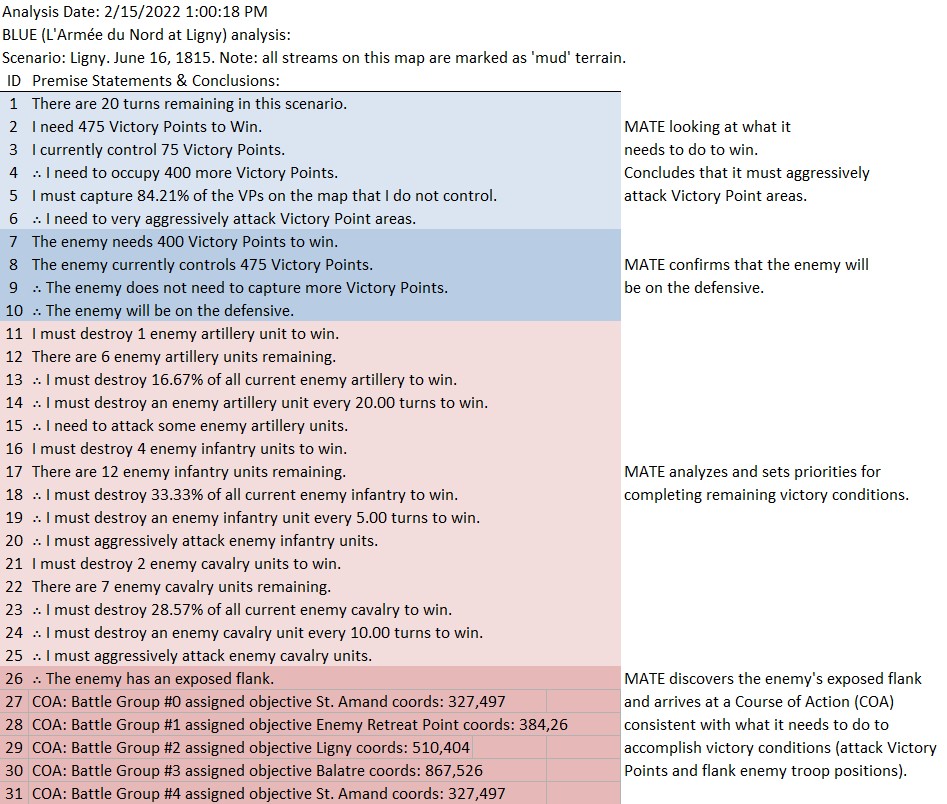

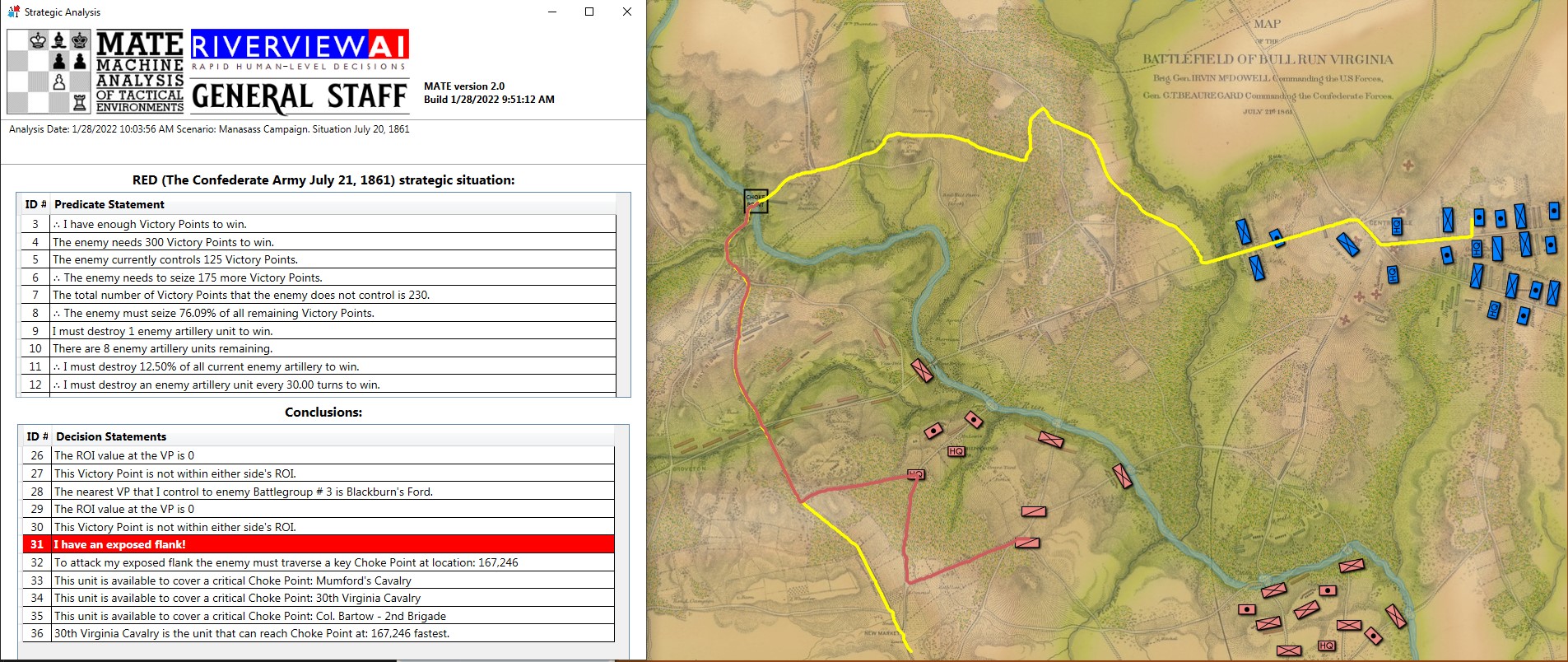

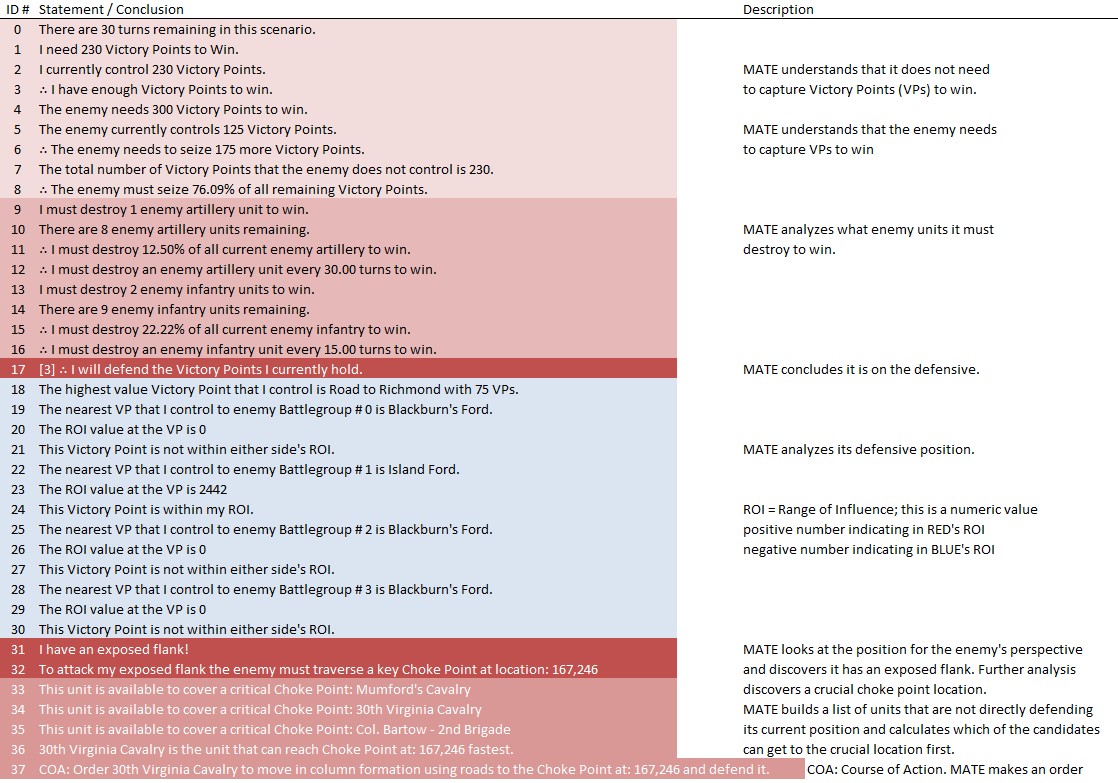

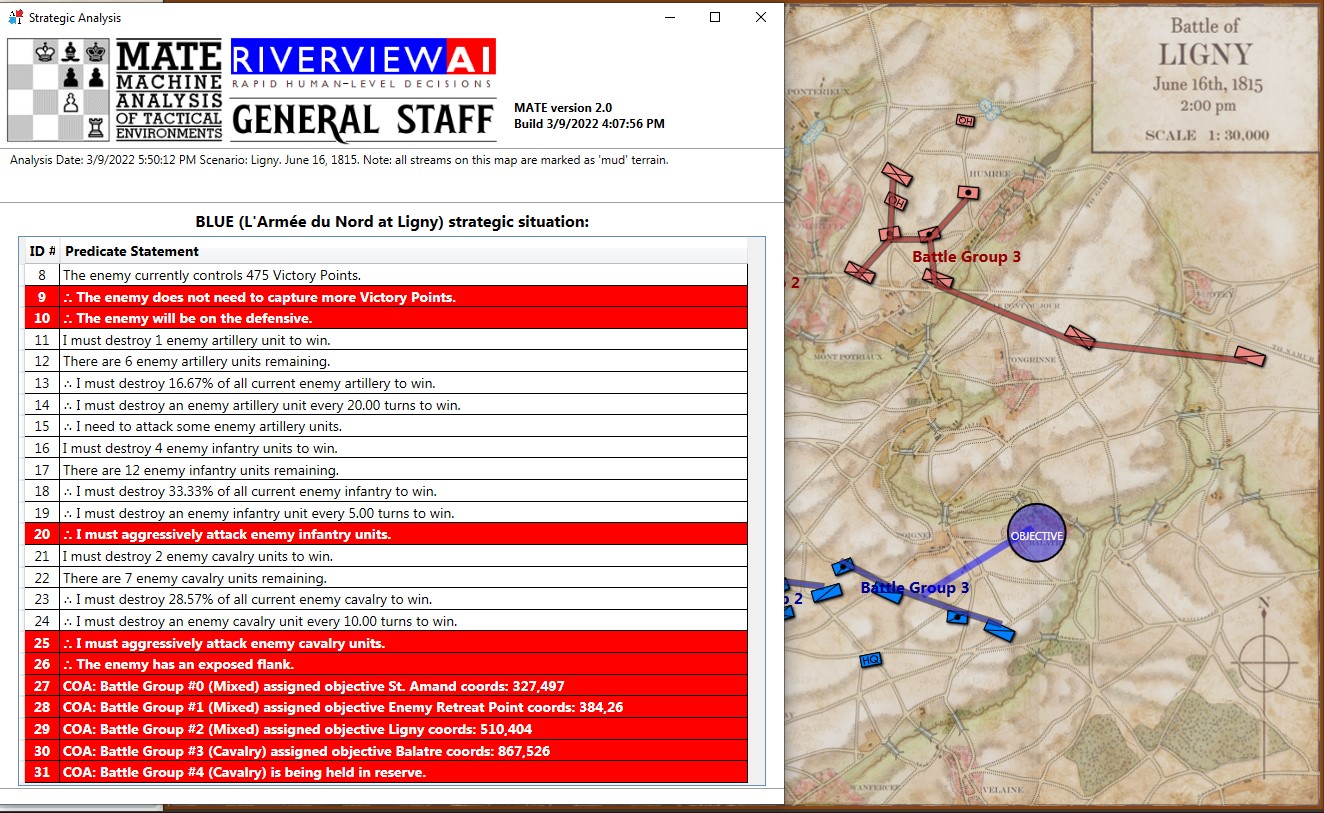

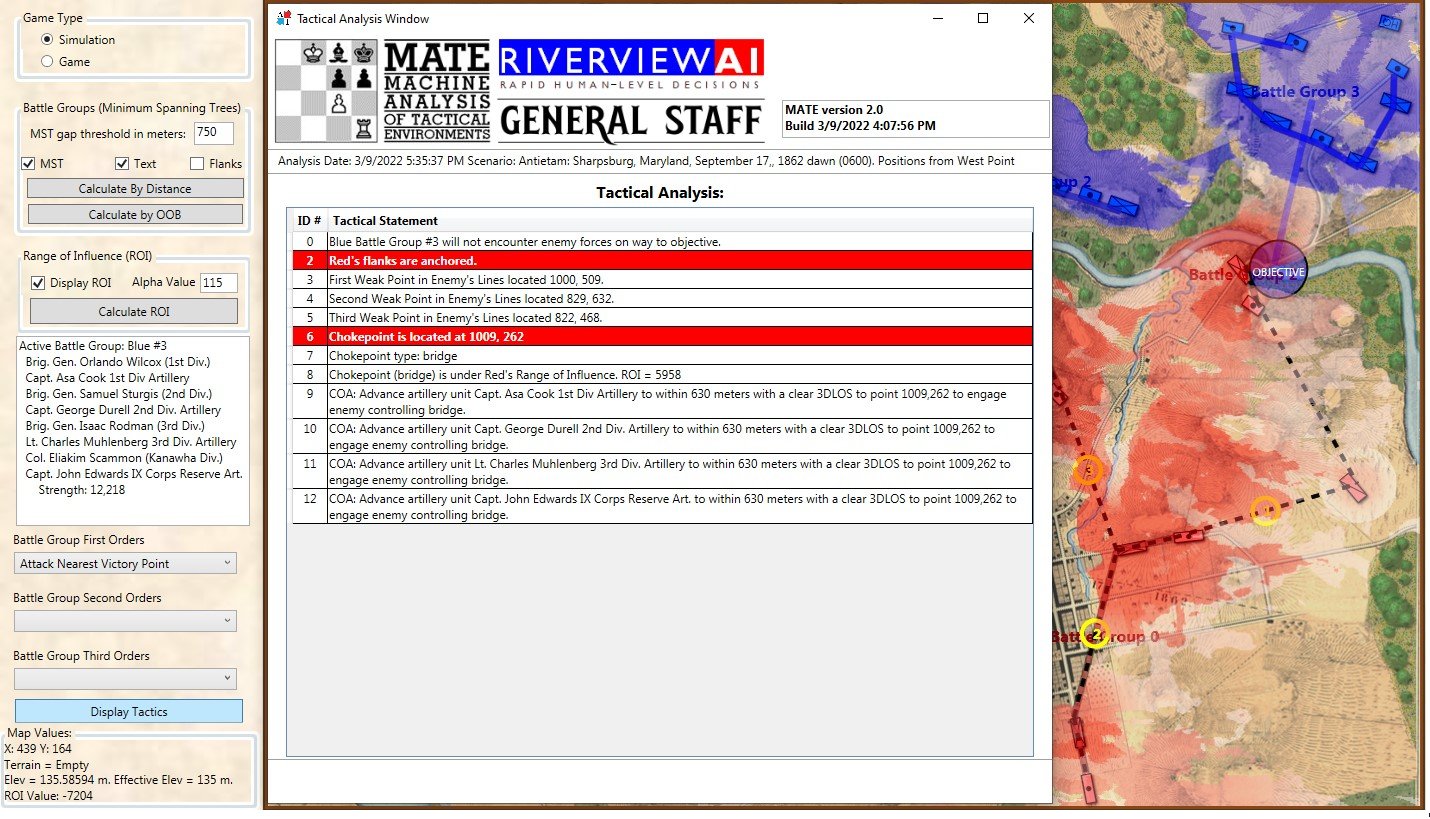

Below is a list of statements, predicates and conclusions generated by MATE during the above analysis with my commentary added on the right:

I recently added a set of algorithms that recognize the composition of battle groups and exploits any possible advantages. For example:

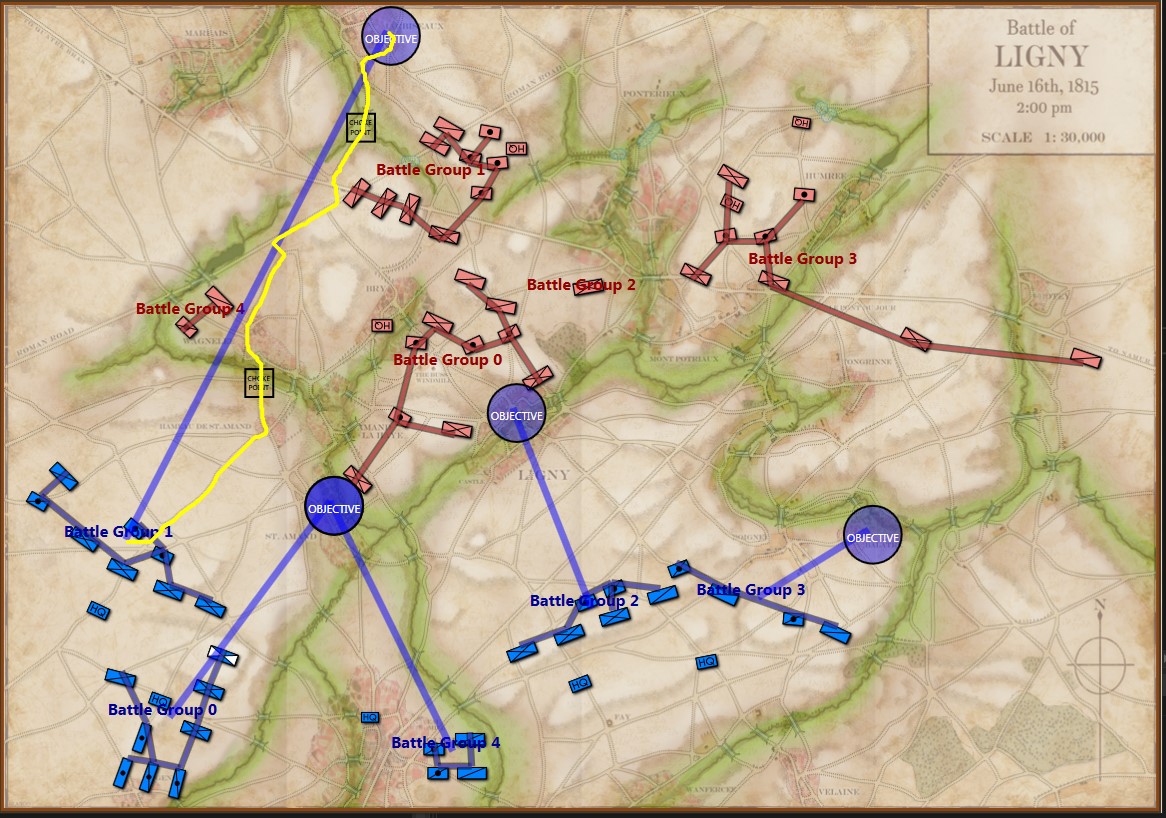

Screen shot showing MATE analysis of BLUE position at Ligny. NB: Battle Group #3 (Pajol’s and Exelmans’ cavalry divisions) are, “snatching the pawn,” at Balatre. Click to enlarge.

At Ligny, above, MATE has recognized that Battle Group #3 and Battle Group #4 are uniquely cavalry (and horse artillery) battle groups and are to be used differently. While Battle Group #4 is held in reserve, Battle Group #3 will snatch Balatre. Though it is valued at only 10 Victory Points, MATE realized that no enemy force could oppose it. That said, I can still hear the voice of my old chess tutor, Mr. Selz, warning me against ‘pawn snatching’; that is grabbing a minor point that can lead to defeat because the position was not thoroughly analyzed. MATE, however, is correct in this analysis and can safely seize the objective.

While, at Antietam, Battle Group #1 (all the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac commanded by Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton) is frozen ‘in reserve’. This is not a case where MATE can snatch a pawn. MATE looked at the situation and said, ‘nope’, there are no unattended Victory Points to snatch and there is not an open flank to exploit so, the default setting is ‘in reserve’.

This leads to the interesting conundrum: what exactly was the Union cavalry at Antietam doing? Honestly, I had never really thought of it before. Now, when I look into the question I find, Was McClellan’s Cavalry Deployment at Antietam Doctrinally Sound? This monograph argues that McClellan massing his cavalry in the center for a great coup de grâce exploitation of a breakthrough across the Middle Bridge was acceptable within the framework of Jomini’s theories as taught at West Point before the Civil War. But, then it is countered with this:

In Landscape Turned Red, Stephen Sears has this to say: Shortly before noon, McClellan had ventured to push several batteries across the Middle Bridge, supported by Pleasonton’s cavalry and a force of regulars from George Syke’s Fifth Corps. He was nervous about the move-it was taken against the advice of Porter and Sykes-and he cautioned Pleasonton not to risk the batteries unduly. As an afterthought, he asked, “Can you do any good by a cavalry charge?” Pleasonton wisely ignored the suggestion. – Sears, Stephen, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1983. page 271. (as cited in above)

Would a great massed cavalry attack across Middle Bridge have been suicide? Or brilliant? For the first time in memory I took the 1st edition of McClellan’s Own Story off the shelf and discovered… nothing. McClellan died suddenly of heart failure just as he was writing about Antietam and his memoirs end abruptly with very little insight into his side of the story. But, using cavalry to support horse artillery – rather than the other way around – seemed a bit odd.

I do not know of any other great cavalry charge in the American Civil War than Sheridan at Five Forks (above). Is this what McClellan envisioned at Antietam? Would it have worked? Could American Civil War regiments have formed square against a massed cavalry charge?

Moving on, let’s drill down to the Course of Action (COA) for Blue Battle Group #3 (Burnside’s IX Corps) at Antietam:

MATE tactical analysis for Blue Battle Group #3 at Antietam (Burnside’s IX Corps). Screen shot. Click to enlarge.

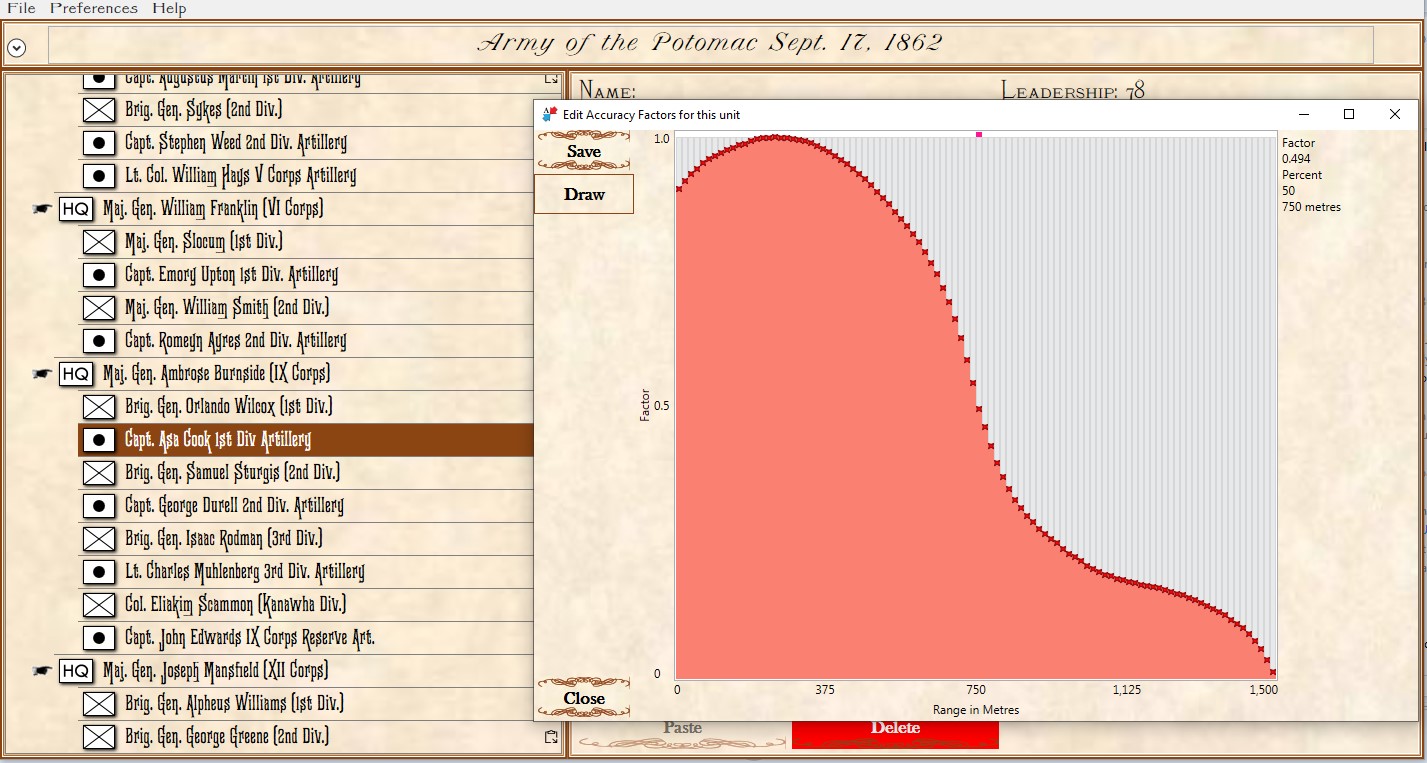

The above is MATE’s output that concludes with the COA for Burnside’s IX Corps. Perhaps, the greatest mystery of the battle of Antietam is what took Burnside so long to take this bridge (now forever linked with his name)? It is true that there were numerous, futile and bloody attempts to cross it. Note that MATE, above, recognizes the bridge as a critical Choke Point. When MATE sees a Choke Point that is within the enemy’s control (see statement #8, above, “Chokepoint (bridge) is under Red’s Range of Influence ROI = 5958″ and 5,998 is very high ROI value) it brings up artillery (see statements #9, #10, #11, #12, above). All the artillery in the IX Corps is to be within 630 meters of the objective. Why 630 meters? Because at that distance it is guaranteed a 50% accuracy rate. This rate, by the way, was set in the Army Editor:

The accuracy curve for the 1st Division, IX Corps artillery as set in the Army Editor. Screen capture. Click to enlarge.

So, MATE says 5)I apologize but I find it easier to describe how the AI works using such phrases as ‘thinks’, ‘says’, and ‘decides’. It’s not worth straining over. Trust me, “My objective is a Choke Point. I’m not sending my units into a meat grinder. I’m sending artillery to a point where they are guaranteed a 50% accuracy per volley and have a clear 3D Line of Sight to the target. This is how I’m going to project as much force as I can at the objective.” War is about force projection. MATE knows this. Is this a better plan than what Burnside actually did? Yeah, it is a lot better with a far greater probability of success. I’ve stood on that plain just east of Burnside’s Bridge and thought that nine batteries of 12 lb. Napoleons aimed at the crest of that hill just beyond the bridge would provide a substantial amount of force projection and covering fire. About half an hour of force projection followed up with an infantry assault would probably take the bridge.

I once described good AI as: Don’t do anything stupid, fast. MATE is doing that. I think MATE is on the way to beat most human opponents because humans do stupid things, fast.

We’ll see. Should be an interesting journey.

References

| ↑1 | MATE: Machine Analysis of Tactical Environments |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | see http://riverviewai.com/download/SidranThesis.pdf |

| ↑3 | a flank that is attached to or protected by terrain, a body of water, or defended fortifications. |

| ↑4 | see pages 45-6 http://riverviewai.com/download/SidranThesis.pdf |

| ↑5 | I apologize but I find it easier to describe how the AI works using such phrases as ‘thinks’, ‘says’, and ‘decides’. It’s not worth straining over. Trust me |